Charles M. Hudson Jr. served as a University of Georgia professor for more than thirty-five years. During his career, he was regarded as the foremost authority concerning the history and culture of Southeastern Indians.

Life

Hudson was born in 1932 and grew up on a family farm in Kentucky. He joined the United States Air Force in 1950 and served with distinction, including a years-long deployment as a communications intelligence specialist in Japan.

Following his military service, Hudson took advantage of the GI Bill, enrolling at the University of Kentucky, where he took an interest in anthropology. After earning his undergraduate degree, Hudson went to graduate school at the University of North Carolina. For his doctoral research, Hudson conducted fieldwork among the Catawba Indians of North Carolina.

Hudson then joined the faculty of the University of Georgia in 1964 as a professor in the anthropology and history departments. He promoted the discipline of anthropology in the South, feeling that it was an understudied region in the field. As a corrective endeavor, he was instrumental in organizing the Southern Anthropological Society, serving as its president in 1973-74. He also served as the president of the American Society for Ethnohistory in 1993. Prior to that, he held a senior fellowship at the Center for the History of the American Indian at the Newberry Library in Chicago during 1977-78. In all, Hudson’s efforts helped to stimulate and bolster a new concentration on the ethnohistory of Southeastern Indians.

Hudson retired as Franklin Professor Emeritus in 2000. After moving back to his native Kentucky, he died in 2013.

Work

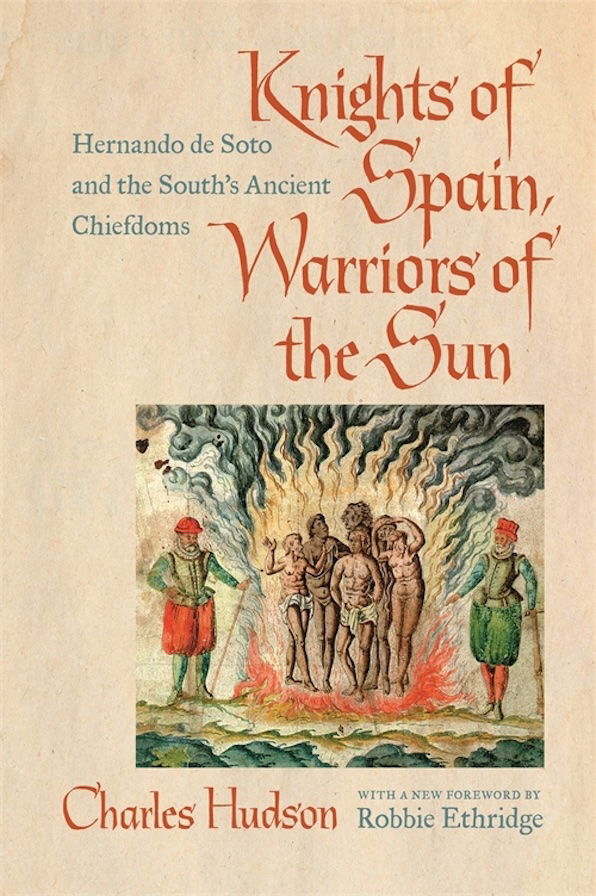

Though he published numerous works across a range of topics, Hudson is primarily known for two seminal books—The Southeastern Indians, which he rightly considered “a standard in the field,” and Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun, an account of Hernando de Soto’s expedition in the Southeast in the sixteenth century. In her scholarly obituary article about Hudson, anthropologist and historian Robbie Ethridge described the latter as Hudson’s “masterpiece.”

Hudson studied European exploration in order to better understand the “discontinuities and continuities” that defined native society before and after European contact. He sought to explain their transition from mound-building peoples, who produced such notable sites as Etowah and Ocmulgee in Georgia, to post-contact societies that no longer built mounds. Meantime, he also hoped to account for the survival of other aspects of native culture, including certain religious beliefs and rituals.

To address these questions, Hudson believed that the routes taken by certain sixteenth century Europeans—not only de Soto, but also Tristán de Luna and Juan Pardo—had to be mapped because accounts of their journeys provide a snapshot of what southeastern Indian life was like at the time of European contact. This snapshot could then serve as a benchmark for assessing changes and continuities in the Native South during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Together with other scholars, Hudson devoted most of the 1990s to this pursuit, publishing a number of articles, chapters, and books.

Hudson later noted that “This research…made it clear that a powerful social transformation occurred among the Southeastern Indians between the 16th and 18th centuries.” Prior to European contact, native societies consisted of “chiefdoms who built large ceremonial earth mounds and produced an impressive array of art forms.” According to Hudson, following European contact, these chiefdoms were transformed “and the survivors reorganized themselves into new kinds of societies. This produced coalescences of people to form such societies as the Creeks, Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws, and Seminoles.”

In the anthology The Forgotten Centuries: Indians and Europeans in the American South, 1521-1704, Hudson and co-editor Carmen Chaves Tesser directed scholars toward understanding the full sweep of that transformation—politically, demographically, socially, economically, and religiously. Many took up the call, and the transformation of the Native South from the Mississippian Period to the nineteenth century came into view.

Having successfully mapped the journeys of European explorers through the Southeast, Hudson next sought “to reconstruct the belief system of people who have undergone massive social collapse.” Regarding continuities between pre- and post-European contact, Hudson concluded “that it is possible to discern a belief system that underlay Southeastern Indian thought for many centuries.” That is, he postulated that a set of beliefs existed before European contact and then continued in some fashion afterward. Hudson stated: “this includes certain broad cognitive schemata, assumptions about the nature of the cosmos…[and] the kinds of beings that exist.” He added that “many of the same animals and anomalous monsters that show up in 18th and 19th-century myths also appear in late prehistoric iconography.”

In an essay published in 2001, Hudson wrote: “People ask me whether I will revise The Southeastern Indians. I tell them that I cannot. What is needed is a new book covering the subject matter in a new way. Perhaps for the first time in my life, I feel that I know how to do this next necessary step. But now that I am retired, I am concerned that I will have enough time and energy to complete it.” Indeed, while he had long planned to produce this one last scholarly book to be titled, Belief System and Ritual in the Native Southeast, he was unable to complete the project.

Legacy

Hudson’s scholarly legacy is secured by the aforementioned The Southeastern Indians and Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. In his retirement, he turned to writing historical fiction (or, as he preferred, “fictionalized ethnography”), including The Packhorseman and The Cow-Hunter. In each of these books, Hudson portrayed an eighteenth-century European navigating cultural differences with native individuals.

Hudson also produced a third fictionalized work that deals with the religious concepts and world view of the pre-contact Indian chiefdoms: Conversations with the High Priest of Coosa. (The paramount chiefdom of Coosa stretched from eastern Tennessee into central Alabama.) He once wrote: “This book depicts how I think they thought.”

Even though Hudson did not finish Belief System and Ritual in the Native Southeast, his final works of fiction drew upon the research and thinking that he had done to plan it.

In addition to his research, Charles M. Hudson Jr. was a devoted teacher, mentor, and colleague who influenced and inspired generations of scholars who have grappled with understanding the native peoples of the Southeast.