The New South and the New Slavery: Convict Labor in Georgia

From the postbellum convict lease system to roadside chain gangs, the use of prison labor and the treatment of those prisoners has long been a source of controversy in Georgia.

Introduction

The introduction of the convict lease system in 1866 made it hard to distinguish the new, post-emancipation South from the old, slaveholding South. States exploited male, female, and even juvenile convicts as a solution to the postbellum economic crisis, and convict labor—particularly that of Black prisoners—would ultimately be used to propel Georgia into the industrial age. Investigations would later reveal appalling living conditions, malnutrition, and widespread physical and sexual violence in Georgia’s prison camps. Under mounting pressure for reform, the state abolished the convict lease system in 1908. But the state-run chain gang took its place, becoming a common sight along roadsides statewide. While chain gangs were outlawed in Georgia in 1943, public works camps and prison farms continued. In recent decades, the contours of the convict lease system have persisted in the form of privatized prisons and contracted inmate labor, some of which reflect the worst abuses of the earlier systems, according to their critics.

The Convict Lease System

Before the Civil War (1861-65), the South’s economy relied on the labor of enslaved people. The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery in the United States and outlawed forced labor—except for use as punishment for a crime. Georgia, along with other southern states, exploited this legal loophole to solve the labor shortage that plagued the region in the postbellum period. In 1866 the Georgia General Assembly legalized the leasing of prisoners to private individuals and companies, creating a new system that retained the brutality of slavery: convict leasing.

On May 11, 1868, Georgia’s first convict lease contract granted 100 prisoners from the State Penitentiary to the Georgia and Alabama Railroad for a period of one year at a cost of $2,500. The following year, all 393 prisoners in the Milledgeville penitentiary were leased to Grant, Alexander, and Company to build the Brunswick and Macon Railroad. In just three years, Georgia’s convicts laid the foundation of more than 450 miles of railway track.

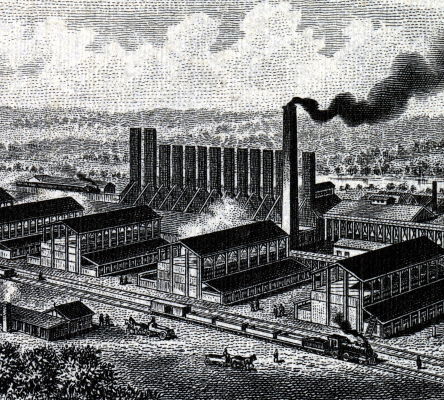

This expansion of transportation jump-started the coal, mining, brick, and rock quarry industries, further increasing the demand for convict labor. Contracts with companies ranged from one- to twenty-year terms, and these businesses became, in effect, designated penitentiaries. Joseph E. Brown’s Dade Coal Company, for example, was known as “Penitentiary Company No. 1.” The state granted these private businesses complete control over the lives of prisoners, who were overworked, underfed, and abused.

Convict leasing cost companies relatively little, and their use of forced labor transformed the South’s broken postbellum economy. When Georgia celebrated the South’s industrial, social, and racial progress at Atlanta’s 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition, signs of the Old South’s presence still loomed as African American chain gangs cleared much of the grounds for the exposition’s construction.

Rooted in Slavery

Georgia’s convict lease system racialized labor from its start. As the demand for cheap labor soared, discriminatory policies and unfair sentencing funneled hundreds more prisoners, most of them African American, into the convict lease system. Notably, that first prison labor contract with the Georgia and Alabama Railroad leased only African American prisoners. Signed by military governor General Thomas Ruger, the agreement assured the company “one hundred able-bodied and healthy Negro convicts.”

Reminiscent of white overseers directing the enslaved, white wardens and Black convicts became frequent subjects of newspaper reports, illustrations, and journal articles. Some of these pieces were intended to expose the system’s underlying prejudices. More often, however, they were used to advance notions of Black criminality. Under the South’s Black Codes, freedpeople too often found themselves arrested for petty crimes like vagrancy. The laws sometimes forced them to enter labor contracts with their former enslavers; those who refused were sent to the chain gang for the crime of “unemployment.” The system targeted Black communities and sent hundreds of Black men and women, some only adolescents, to camps for minor offenses. As a result, Black inmates, and especially young Black men, vastly outnumbered all other prisoners.

Brutality was a common feature of Georgia’s convict camps. Whippings, floggings, sweatboxes, and malnutrition left prisoners’ bodies maimed and scarred, and often resulted in death. Working conditions in mills, mines, brickyards, and rock quarries were dangerous, with railroad laborers moving rail and tamping apparatuses weighing between 100 to 300 pounds and falling brick and slate threatening serious injury.

Prisoners often risked their lives and the lives of fellow inmates to escape the cruel treatment and backbreaking labor of Georgia’s convict camps. Escapees were tracked by bloodhounds and sought after in newspaper “wanted” advertisements and posted broadsides offering generous rewards for their capture. These tactics were not unlike those employed by enslavers searching for fugitives from slavery.

Prisoner Resistance

The ways in which imprisoned men and women responded to the experience of incarceration under the convict lease system often paralleled those of enslaved people. Prisoners used their bodies and imaginations to resist the brutality they experienced. In several Georgia camps, male and female prisoners staged protests and mutinies. Letters from prisoners published in newspapers and in the autobiographies of former convicts were reminiscent of slave narratives, reflecting on the physical, emotional, and social turmoil of incarceration.

Laments born of incarceration also took the form of work songs and field hollers reminiscent of slave spirituals. In musty, cramped mine shafts and under the sweltering Georgia sun, the dirges of prisoners floated on the air and were sent up to the skies. Like the “sorrow songs,” or the “rhythmic cr[ies] of the slave”—as W. E. B. Du Bois characterized slave spirituals and Black folk songs—prison work songs and field hollers were declarations of injustice, agony, and loss captured through words and rhythm. Songs were synchronized with prisoners’ work and sung in a call-and-response style. Tools became instruments: axes used for cutting timber and hammers used to pound railroad stakes supplied the beat and marked pauses between verses. Beatings, starvation, heat, homesickness, missing loved ones, and dreams of freedom were topics to which prisoners returned time and again in song. These melodies formed the soundtracks of prison farms, work camps, and chain gangs.

Women and Children in Convict Camps

Georgia was not only one of the first states to use female convict labor for railroad construction; it also built the first all-female convict camp in 1885. Located in Atlanta, the camp housed female convicts who were required to make the 40,000 odd bricks used to build the adjacent Fulton County Almshouse. The number of Black female prisoners far surpassed the number of white female prisoners. While large numbers of Black men were arrested for vagrancy, many Black women were charged with minor offenses such as arguing or using profane language in public.

Female prisoners were often doubly burdened, performing domestic duties in prison camps and in the homes of white families in addition to strenuous manual labor alongside male prisoners. They cooked, cleaned, and washed and mended clothes. Even while performing demanding and dangerous tasks like breaking rock, shoveling and hauling wet clay, and baking brick near extremely hot kilns, female prisoners were expected to wear striped dresses, a feminine counterpart to the striped shirts and trousers for males. This made them especially vulnerable to accidents. These dresses often caught fire, and many women suffered severe burns as a result.

Though brutal punishment of female prisoners had been ongoing since the inception of the convict lease system, corporal abuse gained national attention in 1903 when a white female prisoner, Mamie De Cris, was whipped by a prison warden for insubordination after refusing his sexual advances. Newspapers covered the incident extensively, and the whipping of female prisoners in Georgia was abolished as a result.

Female prisoners lived in constant fear of sexual assault. Men and women, Black and white, were often chained together at night and slept in the same bunks. In an attempt to mitigate sexual relations and sexual assaults between inmates—and to curb the high pregnancy rate—the state adopted new rules for the penitentiary companies. These rules did little to protect female prisoners from sexual abuse by wardens, however.

Children and adolescents were also victims of Georgia’s convict lease and chain gang systems. Many children were conceived and born in prison camps, and various penitentiary records indicate that an average of twenty-five children lived in the camps in any given year. Male and female juveniles, most of whom were African American, were often charged and sentenced to adult chain gangs for petty crimes like playing dice in the street and trespassing.

Movements for Reform

At the turn of the twentieth century, Progressive Era activists denounced Georgia’s convict lease system. Pamphlets advocating for human rights and newspaper accounts exposing the physical and sexual violence in convict camps flooded the print market. Reformers urged that if the lease system could not be abolished, then major changes to it were needed. Recommended changes included the creation of separate reformatories and camps for women and adolescents, new measures to protect female convicts from sexual assault, and the creation of policies that enforced the humane treatment of prisoners.

Sickened by the lynchings, mob violence, race riots, restrictive laws, and forced labor practices that jeopardized Black lives and civil rights, prominent African American leaders like Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, and Georgia’s Selena Sloan Butler also advocated for prison reform. In local and national women’s club chapters, African American clubwomen spearheaded campaigns.

Women such as Carrie Steele Logan and Martha Holsey founded philanthropic institutions to keep children out of the prison system. In 1907 Holsey, an African American seamstress and clubwoman, worked with the all-white Athens Woman’s Club to establish a Black orphanage and daycare for working mothers. In Atlanta Steele Logan established her Orphan Home, which cared for children born in convict camps, juveniles accused of petty crimes, and children orphaned by the convict lease system. She worked directly with the Atlanta Police Department to send African American adolescents to her orphanage to receive rehabilitation and education rather than be sent to the chain gang.

Advocates for prison reform would compel the state to make small but meaningful changes for vulnerable prisoners. Following a state’s investigation of prison camps in 1897, the Georgia State Prison Farm in Milledgeville was built in 1899 to house female, juvenile, and infirm prisoners. Later, in 1925, the Georgia Commission on Interracial Cooperation, an alliance of white and Black women’s clubs across Georgia, would succeed in securing a Black female jailer to attend the women’s department in a Savannah jail.

Convict Lease Under a New Name

Progressive reformers won a victory when Governor Hoke Smith and the Georgia General Assembly abolished the convict lease system in 1908. For private businesses, the economic repercussions were severe. Without access to cheap labor, many brick and mining companies collapsed, and iron and coal production suffered major financial blows. The same bill that stipulated the end of the lease system, however, outlined a new system of forced carceral labor: the state-run chain gang.

Though chain gangs had existed under convict lease, after 1908, all of Georgia’s prisoners were deployed for work on public projects. The new legislation specified that male and female convicts would be dispersed across the state, performing work to improve county roads and highways. Rather than leasing prisoners to private companies, the state of Georgia allotted a certain number of prisoners to each county.

Many southern white progressives touted the new system as more humane than its predecessor, but prisoners were still poorly clothed, underfed, overworked, and abused. Inmates on the chain gang were transported in overcrowded cages from county to county, where they worked grading roads from sunup until sundown. Once they reached the work site, temporary convict camps called “cage camps” or “road camps” would be set up. Convict cages were used as makeshift prison cells, with as many as twelve inmates packed into spaces of about fifteen feet by seven feet.

As in the convict lease system, male prisoners on the chain gang wore striped shirts and trousers, and female prisoners wore striped dresses. In Georgia, these uniforms were sometimes called “Georgia stripes.” Prisoners were also confined by restraint devices like the ball and chain and “prisoner picks,” a contraption intended to keep prisoners from running away by limiting leg movement.

Just as the convict lease system helped transform the South into an industrial region, state-run chain gangs brought Georgia into the modern age and jump-started its tourist economy by improving road networks. The state’s newspapers and journals touted the use of prisoners in expanding the region’s infrastructure as both advantageous and economical. Georgia was a leader in the “good roads movement.” Prisoners built so many of the state’s roads that “bad boys make good roads” became a popular saying of the time.

Public Outrage and National Cases

The decline of the Georgia chain gang began in the late 1930s after federal investigations and unfavorable media coverage increased awareness of road camps and their deplorable conditions. During the 1930s, several high-profile cases and popular autobiographies brought the issue of penal reform to the forefront of the American consciousness. Robert E. Burns’s 1932 autobiography, I Am a Fugitive From a Georgia Chain Gang!, caught Hollywood’s attention and was adapted for film by Warner Brothers. Burns, a World War I (1917-1919) veteran, was sentenced in 1921 to six to ten years of hard labor on a Georgia chain gang for participating in a robbery of $5.81 from a grocery store. He escaped from the chain gang but was then returned to Georgia’s Troup County Prison Camp, where he escaped once again.

The same year Burns’s autobiography was published, an African American labor organizer named Angelo Herndon was arrested for staging a protest at Atlanta’s Fulton County Courthouse on behalf of Black and white workers across the United States. Prominent activists and the International Labor Defense (ILD), a legal advocacy organization, rushed to Herndon’s aid, and his case gained national attention. An all-white jury convicted him of attempting to incite an insurrection, and a judge sentenced him to eighteen to twenty years on a Georgia chain gang. In 1937 the United States Supreme Court ruled in Herndon v. Lowry, declaring Georgia’s insurrection statute unconstitutional under the First Amendment. The ruling overturned Herndon’s original conviction and set him free. Herndon’s autobiography, Let Me Live, was published in the midst of this trial. Free on bail in 1935, Herndon undertook several speaking tours to publicize his case. To dramatize Herndon’s plight, the ILD constructed a replica of the standard cage sometimes used to house prisoners assigned to a Georgia chain gang.

In 1938, Governor E. D. Rivers banned the term “chain gang” in preference for the more palatable “public works camp” and removed the shackles and chains that bound prisoners together. Yet road gangs continued to operate until Governor Ellis Arnall finally abolished the chain gang in 1943. Even then, prisoners continued to work on farms, roads, and construction projects throughout the state. In 1961 seventy-nine public works camps operated across Georgia. One infamous Georgia prison camp was Buford Prison Rock Quarry, where numerous prisoners had severed their heel tendons to protest labor conditions in 1951. Just five years later, more than thirty prisoners broke their own legs with sledgehammers to protest the demanding and dangerous work they were forced to perform.

At the Georgia State Prison in Reidsville, inmates farmed beef, dairy, and poultry products while also producing vegetables to sustain the prison population. They also labored in the prison’s print shop and its divisions of license plate manufacturing, woodworking, and clothing and shoe repair. Construction of many of the facilities at Stone Mountain Memorial Park, the famous tourist attraction and Confederate monument, was largely completed by inmates.

Protests and publications calling for changes to the prison system put pressure on Georgia officials to institute further reform, with a particular focus on those imprisoned for minor offenses, juveniles in adult prisons, the use of roadside work gangs, and wages for prisoners’ labor. In 1963 Georgia governor Carl E. Sanders initiated a rehabilitation center with a vocational school to be built in Alto for juvenile males under the age of twenty-one. The Georgia Department of Transportation discontinued its use of road gangs in 1973, and protests outside the State Capitol in 1978 urged Georgia to pay prisoners a wage for their labor.

Specters of the Lease System

Traces of the convict lease system remain as forms of convict labor—and debate over their use—continue in penitentiaries today. Across Georgia, prisoners still perform labor for the state—cleaning roadsides, working on prison farms, and maintaining public facilities—with little or no pay. Private companies can hire out Georgia prisoners for labor, with workers being paid significantly below minimum wage to sew clothing, produce food, and manufacture furniture. The Georgia Department of Corrections maintains contracts with private prison corporations, placing thousands of inmates in the care of for-profit companies, and African Americans continue to compose a disproportionate share of the state’s prison population. Policies surrounding prison labor continue to be a source of controversy and a target for reform, not only in Georgia, but nationwide.