The New Georgia Encyclopedia is supported by funding from A More Perfect Union, a special initiative of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Located in Dawson County, Amicalola Falls derives its name from a Native American word meaning "tumbling waters." Amicalola Falls is the highest waterfall in Georgia and among the highest in the southeast.

Photograph by Ryan McKee

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

By the early 1880s Amicalola Falls had become a tourist destination as interest in natural public recreation areas surged following the founding of Yellowstone National Park in 1872. The Kennesaw Gazette, which described the falls as "one of the prettiest cascades in America," was one of many publications to tout the recreational opportunities at Amicalola Falls.

Courtesy of Digital Library of Georgia, Georgia Historic Newspapers.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource may need to be submitted to the Digital Library of Georgia.

Springer Mountain, the southern terminus of the Appalachian Trail, is accessible via an eight-mile trail that begins at Amicalola Falls State Park.

From Amicalola Falls State Park

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Radium Springs, one of Georgia's Seven Natural Wonders, was the site of a casino that had its heyday during the 1920s. The casino was demolished in 2003.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia, #

dgh004.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Georgia Archives.

Radium Springs is a natural cold-water spring located in the eponymously named community of Radium Springs in Dougherty County. It is one of Georgia’s largest natural springs, pumping up to 70,000 gallons of water a minute in ideal conditions. Its waters stay at an average temperature of sixty-eight degrees Fahrenheit year-round and contain naturally occurring trace amounts of radium

From U.S. Geological Survey

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Longleaf pines and wiregrass dominate the landscape of southeast Georgia. Pines can grow quickly on clear-cut land, without competition for resources from other trees, especially hardwoods.

Photograph by Roy Cohutta

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

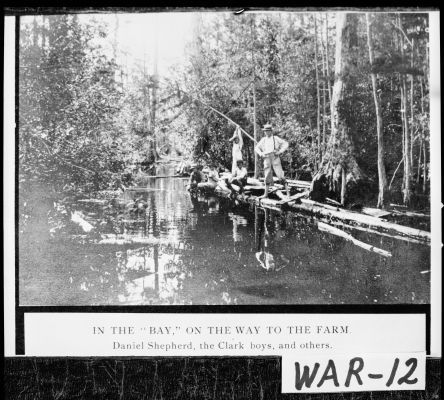

Several local farmers travel through the Okefenokee Swamp in Ware County, circa 1900. At more than 700 square miles, the Okefenokee is the largest swamp in North America.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia, #

war012.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Georgia Archives.

The Franklinia is a deciduous small tree or large shrub growing fifteen to twenty feet high and ten to fifteen feet wide, with elongated, dark green leaves (which turn red, orange, or pink in the fall) and showy two- to three-inch snow-white flowers, with clusters of golden yellow stamens in the centers.

Image from John Donges

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Longleaf pine trees and wiregrass form a distinctive ecosystem in south Georgia. The region's pine forest is divided into three areas: pine and palmetto flats in the east, pine barrens in the interior, and a lime-sink section in the west. Lowland areas of the forest support a variety of other trees as well, including oak, hickory, and cypress.

Photograph by Chris M. Morris

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

An engine stops at a sawmill in Clinch County, at a now-defunct town called Humphries between Dupont and Stockton, in 1893. The mill was located in the wiregrass region of the state, which was heavily logged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia, #cln002.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Georgia Archives.

Anthony Head, a worker in a Lowndes County turpentine still, makes barrels for holding rosin, circa 1900. The naval stores industry formed an important part of the economy in wiregrass Georgia, of which Lowndes County is a part, in the early twentieth century.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia, #

low096.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Georgia Archives.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The Sapelo Island National Estuarine Research Reserve is committed to research, education, and the sound management of coastal resources in Georgia. It lies in an estuary where the currents of Doboy Sound meet the Duplin River.

Courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Estuarine Research Reserve Collection.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

This aerial photograph shows the south end of Sapelo Island and Doboy Sound. Freshwater from the Altamaha River is transported into upper Doboy Sound through the connecting Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway and marsh channels.

Courtesy of Sapelo Island National Estuarine Research Reserve and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Department of Commerce

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The National Estuarine Research Reserve, Sapelo Island.

Courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Estuarine Research Reserve Collection.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Because they tolerate only low-salinity water, Eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica) are found in sounds, estuaries, salt marshes, and tidal creeks. In the early 1900s Georgia produced more oysters commercially than any other state. Today, Georgia's oyster industry is only worth about $100,000.

Courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Estuarine Research Reserve Collection.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Edible shrimps, like this white shrimp (Penaeus setiferus), depend on healthy estuaries for their survival. After spawning in the Atlantic Ocean from late March to September, the larval shrimp enter estuaries, where they feed on bottom algae, small animals, and debris. Within a few months they return to ocean waters as adults.

Courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Estuarine Research Reserve Collection.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Coastal tides bring nutrients from estuaries connected by tidal creeks to the marshes. Outgoing tides carry nutritious marsh products back into the estuaries. There, the products help to sustain large numbers of other marine organisms. The outgoing tides also remove wastes from the marsh.

Courtesy of Georgia Department of Economic Development.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource may need to be submitted to the Georgia Department of Economic Development.

Red drum (Scaenops occelatus), also known as "spottail bass," live the first four years of life in estuaries, where they feed primarily on shrimp and crabs.

Courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Estuarine Research Reserve Collection.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

A marsh in Glynn County is pictured from Jekyll Island in 2004. Poet Sidney Lanier was inspired to write "The Marshes of Glynn" (1879) after a visit to Brunswick. The poem's narrator begins with a rhythmic description of the thick marsh before his vision expands seaward, culminating in an epiphany that the vast marshes and sea are filled with power and mystery.

Photograph by Moultrie Creek

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The salt marsh on Sapelo Island is composed primarily of smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), as are the salt marshes all along the Georgia coast. Other salt-tolerant plants, including needlerush (Juncus roemerianus), compete with Spartina in higher marsh areas, which receive a greater influx of freshwater from the mainland.

Courtesy of Sapelo Island National Estuarine Research Reserve and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Department of Commerce

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Tidal marshes originated around 18,000 years ago, when water from melting glaciers created lagoons behind barrier islands. Clay and sand deposits eventually accumulated in the lagoons and began to support populations of the dominant marsh plant that provides both food and protection to a variety of fauna. The marshes are especially important as nursery grounds for several species of marine life.

Courtesy of Explore Georgia, Photograph by Ralph Daniel.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource may need to be submitted to Explore Georgia.

Smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), the dominant plant species in Georgia's tidal marshes, forms the basis of the salt-marsh food chain. When the plants die, they are broken down by bacteria and fungi into minute particles called detritus, which washes into estuaries and tidal creeks and is consumed by small marine organisms.

Courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Estuarine Research Reserve Collection.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

While alligators often feed in Georgia's salt marshes, the only reptile inhabitants of the marshes are diamondback terrapins (Malachlenys terrapin; adult female pictured). Other animals residing in the marshes include several bird species, as well as raccoons, marsh rabbits, and rice rats.

Photograph by Mary Hollinger, NODC biologist. Courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Department of Commerce

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Set in Glynn County, the poem begins with a rhythmic description of the thick marsh as the narrator feels himself growing and connecting with the sinews of the marsh itself. As his vision expands seaward, he recognizes that the marshes and sea, in their vastness, are the expression of God's greatness and are filled with power and mystery. Read by David Bottoms.Audio by Georgia Public Broadcasting and New Georgia Encyclopedia.

Courtesy of Georgia Public Broadcasting.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to Georgia Public Broadcasting.

A salt marsh extends between the mainland and Sapelo Island, one of the barrier islands lining the Georgia coast. According to estimates by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, salt marshes cover more than 378,000 acres in the state.

Photograph by Darby Carl Sanders

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Blair's Saltpeter Corridor leads into Kingston Saltpeter Cave in Bartow County. The Georgia Speleological Society has documented the existence of at least 513 caves in the state.

Photograph by Joel M. Sneed

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Sixteen species of bats, including gray bats (Myotis grisescens), use Georgia's caves as crucual hibernation or migration habitats. As many as 15,000 gray bats, an endangered species, live in Frick's Cave in Walker County.

Courtesy of Georgia Wildlife Federation

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

A caver descends the Fantastic in Ellison's Cave (in Walker County), one of the largest caves in the country. The Fantastic, at 586 feet, is the deepest straight cave drop in the continental United States.

Photograph by Willie Hunt

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Caver Larry Blair examines vandalism of the "Jug Formation" in Kingston Saltpeter Cave, the only cave in Georgia to be managed as a preserve by the National Speleological Society. Because most caves in Georgia are located on private land, the preservation of caves, including the protection of wildlife within them, often falls to the landowners.

Photograph by Joel M. Sneed

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

This granite outcrop is located at Panola Mountain State Conservation Park in Rockdale County. Most of the granite outcrops in the Piedmont are approximately 300-350 million years old.

Photograph by Melinda Smith Mullikin, New Georgia Encyclopedia

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Stone Mountain Park encompasses 3,200 acres just sixteen miles east of downtown Atlanta. Formed around 300 million years ago during the Paleozoic Era, the mountain itself is the world's largest mass of exposed granite.

Image from Darryl Pierce

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

This Panola granite, found at Panola Mountain State Conservation Park in Rockdale County, differs in mineral composition and texture from the granite outcrops at nearby Stone Mountain and Arabia Mountain.

Photograph by Chad A. S. Mullikin

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Visually, sandhills are often striking as islands of exposed sand and sparse vegetation in the midst of denser forest. Sandhills are characterized by thick sandy deposits one to twenty-five meters deep.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Sandhills form the prime habitat of Georgia's state reptile, the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus).

Courtesy of James H. Miller, USDA Forest Service, www.forestryimages.org

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Stone Mountain is the largest exposed mass of granite in the world. It was once used by Native Americans as a ceremonial place. Today, Stone Mountain Park is owned by the state of Georgia.

Image from G. DAWSON

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The town at the base of Stone Mountain was founded in 1847. The expansion of Georgia's railways connected Stone Mountain to residents in Atlanta and as far away as Augusta.

Photograph by Daniel Meyer, Wikimedia

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The Memorial Lawn at Stone Mountain is used as a viewing area for the park's summer laser show. During the winter the park provides snow tubing for visitors on the lawn.

Photograph by Chris Yunker, Wikimedia

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

An unknown group on a bus trip tours the site of Stone Mountain in June 1929. Work on a Confederate memorial had begun on the side of the granite mountain, but the carving would not be completed until the 1950s.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia, #cob162b.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Georgia Archives.

The carving on Stone Mountain depicts the Confederate icons Robert E. Lee, Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson, and Jefferson Davis. Commissioned by the president of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the sculptor Gutzon Borglum began work on the relief in 1915. He was fired in 1925, and Augustus Lukeman completed the carving.

Photograph by Mark Griffin, Wikimedia

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The "Confederate Daisy," or "Stone Mountain Yellow Daisy," grows in the shallow soil on the granite outcrops of Stone Mountain. The flower is so named because it is found only within a sixty-mile radius of the mountain. The species was discovered in 1846.

Photograph by Lee Coursey

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The unconsolidated sandstone bluffs of Providence Canyon in Stewart County were formed during the Cretaceous Period and are among the oldest exposed Coastal Plains rock formations in the state.

Courtesy of Matthew M. Moye

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Providence Canyon, pictured in 1893, is a network of gorges created by soil erosion in Stewart County. Historical accounts indicate that the canyon began to form in the early 1800s as a result of poor farming practices.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia, #

stw002.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Georgia Archives.

Identified by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources as one of the state's "Seven Wonders," the site is protected by Providence Canyon State Park, located approximately 150 miles southwest of Atlanta, in Stewart County.

Courtesy of Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource may need to be submitted to the Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

Once a leading destination for tourists in the Southeast, Tallulah Gorge still attracts numerous visitors, particularly in the fall when the mountainsides are ablaze with color.

Photograph by Jeno

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

In 1992 the state, in partnership with Georgia Power, created Tallulah Gorge State Park, one of the most popular in Georgia's park system. Controlled releases from the dam allow visitors to hear the roar of the falls on selected weekends in the spring and autumn.

Photograph by Jeno

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Tempesta Falls is located in northeast Georgia's Tallulah Gorge State Park, near the Rabun and Habersham county line. Tempesta, one of a series of four main cataracts that make up Tallulah, today only roars to life on selected weekends in the spring and autumn.

Photograph by Mark Morrison

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

George Cooke's Tallulah Falls (1841) features elements typical of the Hudson River School of landscape painting, particularly in its depiction of the picturesque and sublime. Tallulah Falls, located in the northeast Georgia mountains, comprises four waterfalls, three of which Cooke captures in his painting. Oil on canvas (35 3/4" x 28 3/4").

Courtesy of Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia; gift of Mrs. William Lorenzo Moss. GMOA 1959.646

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

A train on the Tallulah Falls Railway travels through Cornelia, in Habersham County, in the 1930s. Completed in 1907, the railroad ran from Cornelia to Franklin, North Carolina, stopping at Tallulah Falls along the way.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia, #

hab046.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Georgia Archives.

Helen Dortch Longstreet, the second wife of General James Longstreet, is remembered for her unflagging work as a Confederate memorialist, progressive reformer, and a librarian and postmistress. She is also known for her unsuccessful efforts to prevent the damming of Tallulah Falls in northeast Georgia.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Rufus L. Moss Sr., pictured in 1853, was a prominent Athens businessman who played a vital role in the development around Tallullah Falls and Gorge. In addition to founding the first hotel in the area, the Cliff House, in 1882, Moss cofounded the town of Tallulah Falls and worked to bring the Northeastern Railroad into the region. In 1909 he sold his significant land holdings to the Georgia Power Company, paving the way for the electrification of Georgia.

Courtesy of Mary Bondurant Warren

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The Cliff House Hotel, built in 1882 by Rufus L. Moss Sr., was the first lodging establishment in Tallulah Falls. The hotel served the thriving tourist industry until 1937, when it burned in a kitchen fire.

Courtesy of Rabun County Historical Society

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The "Old Hotel," as Tallulah Falls locals called it, pictured in the 1930s. Many people came from all over Georgia (and beyond), some via the Tallulah Falls Railroad, to bathe in and enjoy the springs in the surrounding area. The resort was built in the 1800s.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia, # rab033.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Georgia Archives.

Once a leading destination for tourists in the Southeast, Tallulah Gorge still attracts numerous visitors, particularly in the fall when the mountainsides are ablaze with color.

Photograph by Martin Bravenboer

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

A great egret perches on a branch in the Okefenokee Swamp.

Photograph by Siddharth Sharma

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) is one of the most ecologically dominant species in the Okefenokee Swamp.

Courtesy of Georgia Department of Economic Development.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource may need to be submitted to the Georgia Department of Economic Development.

Cypress swamps, winding waterways, and floating peat mats are a major part of the Okefenokee's habitat mosaic.

Image from Timothy J

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The Okefenokee Swamp's ecosystem is home to a diverse assemblage of animals and plants, none of which are unique to the swamp, but which together create an unusual biodiversity found in few places in the United States.

Courtesy of Explore Georgia, Photograph by Geoff L. Johnson.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource may need to be submitted to Explore Georgia.

Virtually all species of wading birds and waterfowl native to the Southeast can be found in the Okefenokee in some season. Sightings of great egrets, wood storks, blue herons, and white ibises are common.

Image from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Alligators are among the hundreds of animal species to make their home in the Okefenokee Swamp.

Courtesy of Explore Georgia, Photograph by Geoff L. Johnson.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource may need to be submitted to Explore Georgia.

The green tree frog can be found in wetlands of Georgia, including the Okefenokee Swamp. The chorus of these frogs during the spring and summer months can be almost deafening.

Image from Vicki DeLoach

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Alligators, which are native to Georgia, are among the hundreds of animal species to make their home in the Okefenokee Swamp.

Courtesy of Georgia Department of Economic Development.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource may need to be submitted to the Georgia Department of Economic Development.