An artist accomplished in several media, Atlanta native Emma Amos explored difficult issues concerning politics, gender, race, and cultural history in her work. Her highly expressive visual art combined printmaking, painting, and textiles with photography and collage. She was also known as a teacher, curator, writer, and activist.

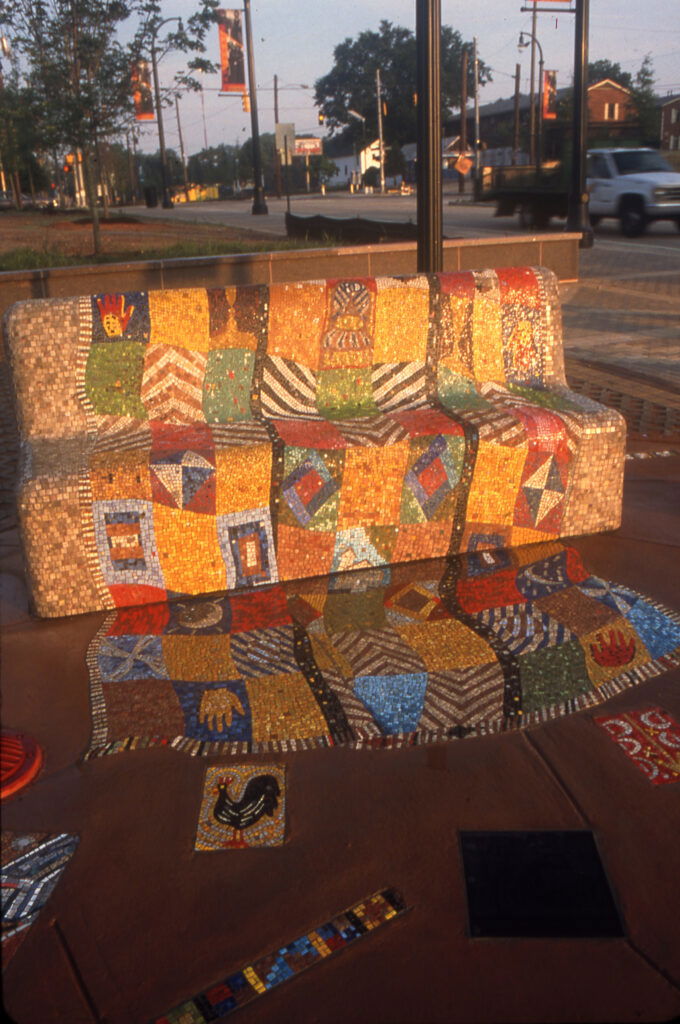

Amos designed a glass mosaic bench, bronze chair, and gazebo with mosaics and plantings, situated on three large ovals, as part of the Ralph David Abernathy Memorial Plaza in Atlanta. Completed for the Olympic Games in 1996, this permanent art and landscaping installation was commissioned by the Corporation for Olympic Development in Atlanta to honor civil rights activist Ralph David Abernathy.

Family and Education

Amos was born on March 16, 1938, in Atlanta to India DeLaine Amos and Miles Green Amos. Biographical references permeate much of Amos’s work. In Atlanta, where her family has lived for generations, she grew up in the rich cultural environment surrounding the middle-class African Americans of the city. She and her older brother, Larry, were nurtured and uplifted by this insular community. She payed homage to her family in the print series Odyssey, created in 1988.

Amos’s maternal grandfather, Moses Amos, was born in 1866, the first of his siblings to be born free. He was the first registered African American pharmacist in the state of Georgia. His wife, Emma, the artist’s namesake, was of Cherokee, African, and Norwegian ancestry and graduated from the college that became Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University). Their daughter, India DeLaine Amos, was a 1931 alumna of Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee.

Amos’s paternal great-grandfather, an Irishman whose surname was Donnelly, reared his daughter Minnie to be a servant for her white half sisters. Miles Green Amos, Minnie’s son, left Atlanta for Ohio, where he graduated from Wilberforce University and the Cincinnati College of Pharmacy. Upon his return to Atlanta, he married India DeLaine Amos, and the couple, who were cousins, co-owned Amos Drug Store. The family had the means to enjoy rich cultural experiences within their community but also suffered the indignities of segregation. This included, for Emma Amos and her brother, an often second-rate education in the public school system.

Even as a young child, Amos knew that she would be an artist. When she was eleven, she took art lessons from Ruth Hall Hodges at Morris Brown College in Atlanta. Her parents knew Hale Woodruff, who developed the art department and established the annual African American art exhibitions at Atlanta University. Although Woodruff would not take her as a private student, his support was crucial when Amos was living in New York City years later. Recognition of her talent extended beyond her family, and her work was included in several annual exhibitions at Atlanta University.

In 1954, at the age of sixteen, Amos left Atlanta to attend Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, where she majored in art and took courses in weaving. As part of the work-study program, she also spent part of each academic year working in Chicago, Illinois; New York City; and Washington, D.C. In her fourth year, she enrolled at the Central School of Art and Design in London, England, where she studied painting with William Turnbull and etching with Tony Harrison. Amos graduated from Antioch in 1958, then returned to London to complete her studies; she was awarded a diploma in 1960. During her time in Europe she became increasingly aware of the expressive properties of color and the sense of movement in the work of the abstract expressionists.

Career

Amos next spent a year in Atlanta, where the New Arts Gallery held the first solo exhibition of her prints in 1960. She then relocated to New York City, which she called home for the better part of the next six decades. In New York she embarked upon a career as a textile designer with noted designer Dorothy Liebes, and studied etching with Letterio Calapai at Atelier 17 in Greenwich Village and lithography with Bob Blackburn at his Printmaking Workshop. She also attended New York University and received a master’s degree in 1966.

During this period Amos became reacquainted with Hale Woodruff, who was teaching in New York; he was impressed with her work and in 1964 invited her to become a member of Spiral, a group of approximately fifteen prominent African American artists who exhibited together and met for weekly discussions. Amos was the youngest and only female member. She joined the weekly meetings for two years until the group disbanded.

After a five-year courtship, she and Robert Levine married in 1965. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Amos curtailed her activities while the couple’s two children, India and Nicholas, were young. She taught weaving in Greenwich Village and at the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Art in New Jersey. For the 1977–78 season, she created and cohosted Show of Hands, a program produced by the educational television station WGBH in Boston, Massachusetts, that explores the intersection of traditional crafts and art.

In 1980 Amos began teaching at the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University in New Jersey, where she was a professor until she retired in 2008. Interested in feminist issues, she played a prominent role in several feminist collectives, including the magazines Heresies and M/E/A/N/I/N/G. In 1994 she was appointed chair of the board of governors for the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine, and in 1996 she continued as cochair with artist David Reed.

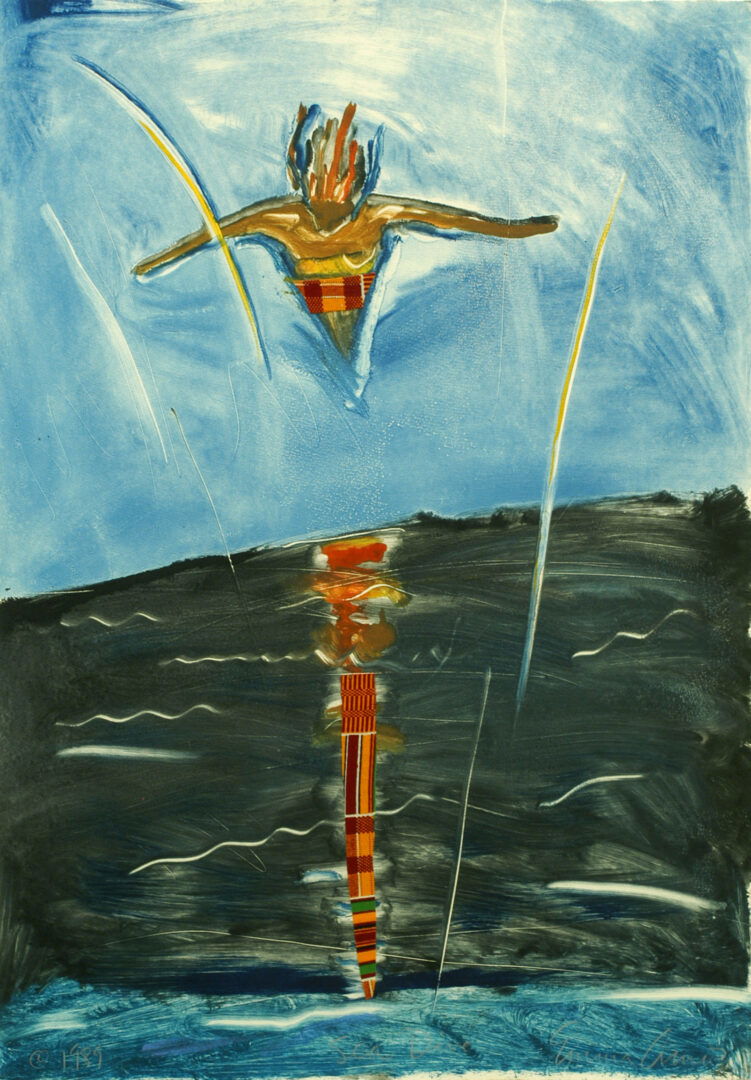

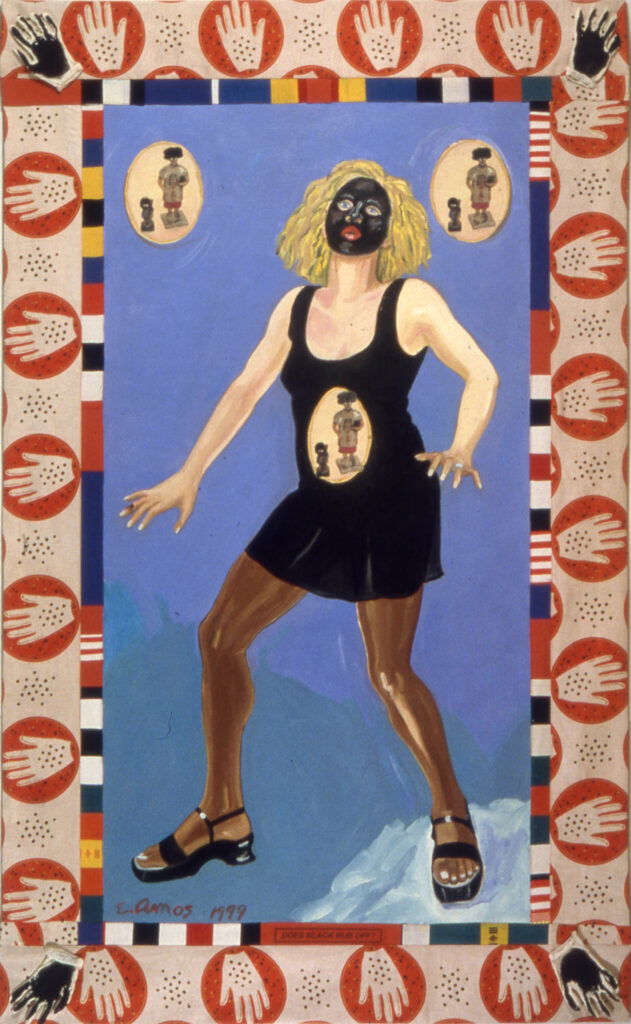

By the 1980s Amos’s style was fully developed. Complex in design and meaning, her work demands much of the artist and the viewer. Amos often works in overlapping series of mixed-media prints and paintings that explore such issues as family and friends, flawed heroes, self-censorship, feminism, racism, multiculturalism, and political identity. She carefully titles her work with subtle references to popular culture, African history, and politics, and often responds to acclaimed masterpieces of modern art.

Amos’s technique reflected her diverse training and contained distinctive features. Multihued figures that populate many of her images are often seen in motion, floating, falling, and extending beyond the picture plane. Textiles are used to add color and texture. Woven fabric, either African textiles or her own weaving, borders her work and is meant as an anchor and a point of context and connection. Powerful symbols proliferate—Xs, handprints, eyes, and flags vary in placement and meaning.

Amos’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, and she received numerous awards and accolades, including a Georgia Women in the Visual Arts Award in 1997.

Her work is part of many public collections, including those of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., the Morris Museum of Art in Augusta, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York.

Amos died on May 20, 2020, of natural causes, after a prolonged battle with Alzheimer’s Disease. In the years since, her work has been exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. A career retrospective, “Color Odyssey,” premiered at the Georgia Museum of Art in 2021, and then traveled to the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in Utica, New York, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.