Between 1735 and 1750 Georgia was the only British American colony to attempt to prohibit Black slavery as a matter of public policy. The decision to ban slavery was made by the founders of Georgia, the Trustees.

Slavery Banned

General James Oglethorpe and the other Trustees were not opposed to the enslavement of Africans as a matter of principle. They banned slavery in Georgia because it was inconsistent with their social and economic intentions. Given the Spanish presence in Florida, slavery also seemed certain to threaten the military security of the colony. Spain offered freedom in exchange for military service, so any African captive brought to Georgia could be expected to help the Spanish in their efforts to destroy the still-fragile English colony.

The Trustees wished to guarantee the early settlers a comfortable living rather than the prospect of the enormous personal wealth associated with the plantation economies elsewhere in British America. They would obtain this living by working for themselves rather than being dependent upon the work of others. The Trustees believed that the silk and other Mediterranean-type commodities they envisaged for Georgia did not require the labor of enslaved Africans but could be easily produced by Europeans.

Initially the Trustees believed the settlers would follow their wishes and not use enslaved workers. Oglethorpe realized, however, that many settlers were reluctant to work. Some settlers began to grumble that they would never make money unless they were allowed to employ enslaved Africans. Many South Carolinians, who wanted to expand their planting interests into Georgia, encouraged this line of thinking.

Oglethorpe soon persuaded the other Trustees that the ban on slavery had to be backed by the authority of the British government. The influential Trustees easily persuaded the House of Commons that their intentions for Georgia, and the colony’s very survival in the face of the Spanish threat, depended upon the exclusion of enslaved Africans. In 1735, two years after the first settlers arrived, the House of Commons passed legislation prohibiting slavery in Georgia.

Slavery Demanded

Georgians’ campaign to overturn the parliamentary ban on slavery was soon under way and grew in intensity during the late 1730s. Its two most important leaders were a Lowland Scot named Patrick Tailfer and Thomas Stephens, the son of William Stephens, the Trustees’ secretary in Georgia. They and their band of supporters bombarded the Trustees with letters and petitions demanding that slavery be permitted in Georgia. They also wrote pamphlets in which they set out their case in more detail.

The crux of their argument was that the Trustees’ economic design for Georgia was impractical. They insisted that it would be impossible for settlers to prosper without enslaved workers. West Africans, they argued, were far more able than Europeans to cope with the climatic conditions found in the South. As the growing wealth of South Carolina’s rice economy demonstrated, enslaved workers were far more profitable than any other form of labor available to the colonists. Tailfer and Thomas Stephens wanted to recreate the slave-based plantation economy of South Carolina in the Georgia Lowcountry.

The Trustees replied to those settlers they depicted as ungrateful “malcontents” by repeating the arguments that had persuaded them to ban slavery in the first place. They also pointed out that not all Georgia colonists were demanding that slavery be permitted in the colony. They received important backing for their policy from two groups of settlers. In a petition sent to the Trustees in 1738, the Highland Scots who had settled in and around Darien expressed their unequivocal support for the continuing ban on slavery. Pastor Johann Martin Boltzius expressed similar sentiments on behalf of the Salzburger community at Ebenezer.

Before the late 1730s, the Trustees were not under any serious pressure to lift the ban. All this began to change when Thomas Stephens realized that financial pressure could be brought to bear on them. Because the Trustees depended upon the British House of Commons to finance the continuing settlement and defense of Georgia, Stephens tried to persuade the House to make its financial support conditional upon the introduction of slavery. He spent time in London lobbying members of Parliament and trying to secure a broad base of public support for his arguments. Thanks to the political influence of the Trustees, his efforts bore little fruit. As long as Spain remained a threat, the British Parliament was willing to invest money into the Georgia project.

The situation changed dramatically in 1742 when Oglethorpe defeated the Spanish at the Battle of Bloody Marsh and returned to England. The military arguments in favor of prohibiting slavery were no longer tenable. In Oglethorpe’s absence a growing number of settlers became more willing to ignore the ban on slavery.

By the mid-1740s the Trustees realized that excluding slavery was rapidly becoming a lost cause. Oglethorpe had virtually lost interest in Georgia by this time, and the health of Egmont had begun to deteriorate. In the absence of their strong leadership, there was little to prevent the Georgia settlers, with the connivance of South Carolina sympathizers, from illicitly importing enslaved Africans primarily through the Augusta area.

The Trustees, bowing to the inevitable, agreed that the ban on slavery be overturned but only after they had consulted their officials in Georgia about the conditions under which slavery would be permitted. In opposition to South Carolina’s slave code, the Trustees wished to ensure a smaller ratio of Blacks to whites in Georgia. These consultations were completed by 1750. The Trustees asked the House of Commons to replace the Act of 1735 with one that would permit slavery in Georgia as of January 1, 1751. The legislation they recommended was adopted. The Trustees’ desire to exert an influence on the pattern of slavery and race relations in Georgia, even after their Royal Charter expired in 1752, proved very short-lived.

Slavery Permitted

The lifting of the Trustees’ ban opened the way for Carolina planters to fulfill the dream of expanding their slave-based rice economy into the Georgia Lowcountry. The planters and the people they enslaved flooded into Georgia and soon dominated the colony’s government. In 1755 they replaced the slave code agreed to by the Trustees with one that was virtually identical to South Carolina’s. This code was amended in 1765 and again in 1770.

The South Carolinian migrants enjoyed a significant wealth advantage over the original settlers of Georgia. They quickly established socioeconomic structures and relationships that were nearly identical to those they had known in their own colony. Within twenty years some sixty planters who owned roughly half the colony’s rapidly increasing enslaved population dominated the apex of Lowcountry Georgia’s rice economy.

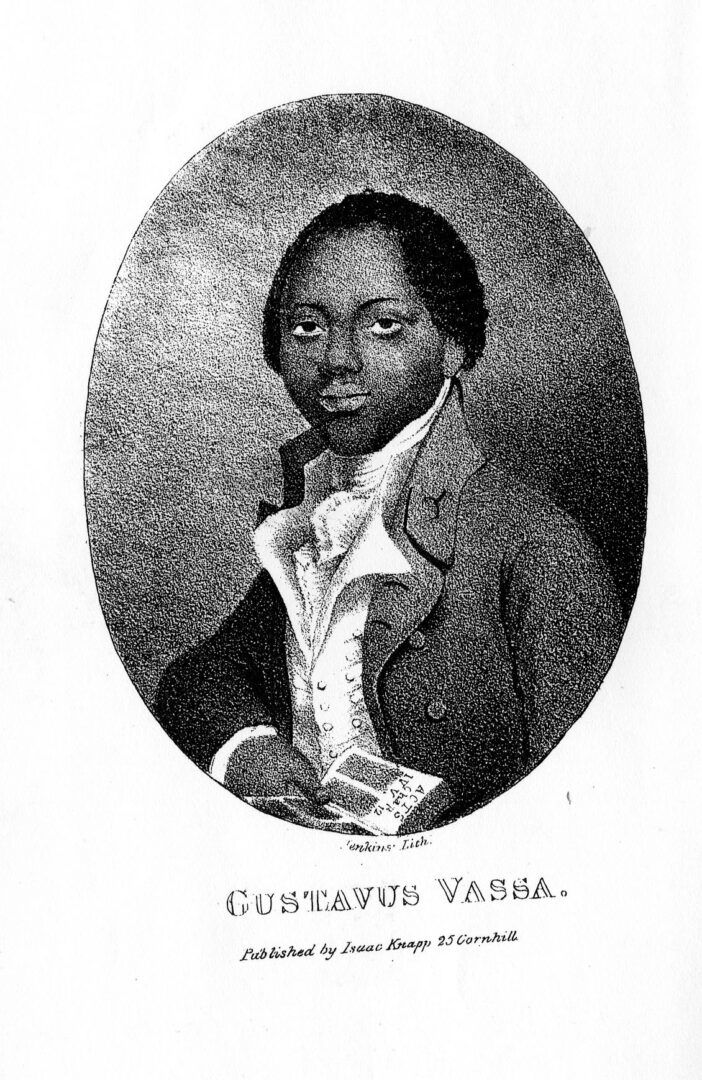

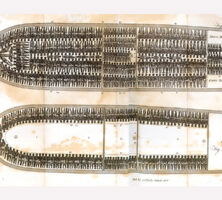

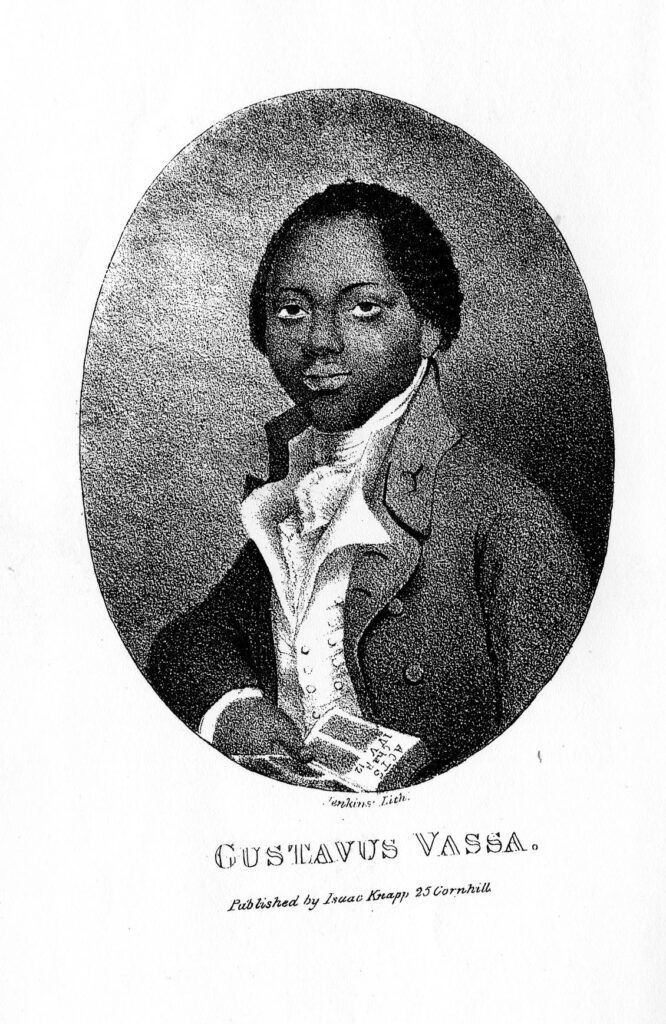

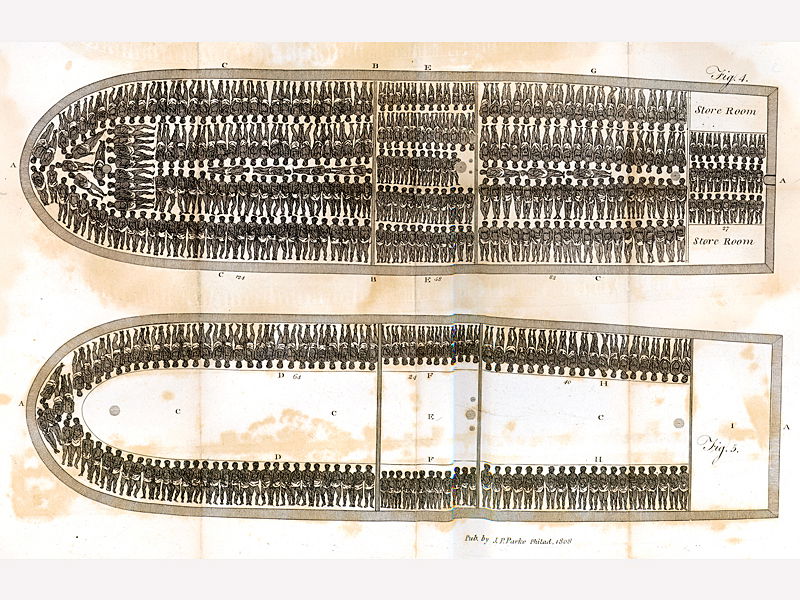

Between 1750 and 1775 Georgia’s enslaved population grew in size from less than 500 to approximately 18,000 people. Beginning in the mid-1760s, Georgia began to import captive workers directly from Africa—mainly from Angola, Sierra Leone, and the Gambia. Most were given physically demanding work in the rice fields, although some were forced to labor in Savannah’s expanding urban economy.

Enslaved individuals had no legal right to private lives, and they struggled against daunting odds to establish some degree of autonomy for themselves. With varying degrees of success, they tried to recreate the patterns of family and religious life they had known in Africa. The circumstances of slavery in the Georgia Lowcountry precluded the possibility of organized rebellion. Yet enslaved people resisted their owners and asserted their humanity in ways that included running away as well as acts of verbal and physical violence. The American Revolution (1775-83) would offer them the best prospect of freedom.

By the mid-1750s the earlier debate on the introduction of slavery to Georgia seemed never to have taken place. Almost every white person in the Georgia Lowcountry at that time believed that the institution of slavery was essential to his or her economic prosperity. During the remainder of the colonial period, no white Georgian voices were raised to challenge that assumption.