“Covers Dixie Like the Dew:” A History of Newspaper Journalism in Georgia

Print journalism in Georgia began in 1763 when James Johnston established the state’s first newspaper, the Georgia Gazette, in Savannah. More than 250 years later, newspapers continue to play an essential role in the state's public life.

Introduction

Since their inception in 1763, newspapers in Georgia have printed a first draft of the history of the state and its people. These publications not only recorded events, but also reported the beliefs and attitudes of Georgians, documenting their successes and shortcomings. More than just a mirror of society, newspaper journalism has also been an influential voice in the affairs of the state and helped shape Georgia’s view of itself and the world. Such disparate journalists as Henry W. Grady and John H. Deveaux used their papers to paint an aspirational picture of what Georgia and the rest of the South might become. Through turmoil, division, and change, Georgia’s newspaper industry survived and thrived in its mission to deliver the news to readers across the state. Over time, Georgia’s newspapers diversified and increasingly came to reflect the different identities, viewpoints, and beliefs of its people.

Early Georgia Newspapers

Print journalism in Georgia began in 1763 when James Johnston established the state’s first newspaper, the Georgia Gazette, in Savannah. Georgia’s colonial legislature designated Johnston, an immigrant from Scotland, the Royal Printer for the colony. In addition to printing the government’s laws, he used the opportunity to establish Georgia’s first newspaper. The inaugural issue of the Georgia Gazette ran on April 7, 1763, containing local and international news items, an inventory of goods shipped into Savannah, and advertisements for both fugitives from slavery and the sale of an island.

Johnston took a neutral stance on the politics of the day and printed both the laws of the colonial government and news of discord among the colonists. This neutrality put him at odds with the Patriots in Georgia, and he fled the state in 1776. When the British recaptured Savannah in December 1778, Johnston returned to the city to print the Royal Georgia Gazette. On January 30, 1783, after the British abandoned their positions in Savannah, the state government allowed Johnston to continue publishing under a new title, Gazette of the State of Georgia.

Johnston and his son would continue to print newspapers until 1802, by which time they faced competition as newspaper journalism began to proliferate across the state. In 1785 the state officially moved the seat of government from Savannah to Augusta. During this period, several newspapers appeared in the new capital. The first of these was the Augusta Gazette, which began circulation in August of that same year. The modern-day Augusta Chronicle traces its roots to the publication, making it the oldest newspaper in Georgia still in print. A second newspaper, the Southern Centinel, and Universal Gazette, began publication in 1793, making Augusta the first city in Georgia with multiple newspapers in print. Two more newspapers appeared in Savannah that same decade, while the State Gazette and Louisville Journal began publication in the state’s newly appointed capital, Louisville, in 1798. By the turn of the eighteenth century, there were five newspapers in print in Georgia, and by 1812, there were at least twenty. Much of that growth came in smaller cities and towns, including Athens, Milledgeville, Washington, and Sparta.

Diversity in Media

Newer publications took on a more partisan tone than their predecessors, reflecting the rise of political parties in the United States in the late eighteenth century. But even as they reflected an increasing variety of public opinion, the state’s early newspapers shared one thing in common: they were largely produced and published by white men.

Women were discouraged and often outlawed from operating businesses in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. However, an exception was sometimes made for women who were widowed without a male heir to run their deceased husband’s affairs. It was under this set of circumstances that, at the turn of the nineteenth century, Sarah Porter Hillhouse broke Georgia’s print journalism gender barrier.

In 1801, Sarah’s husband David purchased Washington’s first newspaper, the Washington Gazette, retitling it the Monitor. After David’s death in 1803, Sarah continued publishing the paper, becoming the first woman to serve as a publisher and editor of a newspaper in the state’s history. Her four-page, four-column weekly was characteristic of the time, with reprinted national and international news, state laws, and local ads. During her tenure, she built a professional reputation that earned her government contracts to print legislative documents. By 1813, after nearly a decade of publishing the Monitor, Hillhouse had passed publishing responsibilities of the paper to her son, David.

Hillhouse’s extended editorship of the Monitor made her one of a small number of early American women to oversee a paper’s publication for a period of multiple years. But despite the rarity of her role, there’s little evidence that she advocated for an expansion of women’s rights more generally. But newspapers could—and did—support community development and social justice, as evidenced by the Georgia’s most distinctive paper of the era, the Cherokee Phoenix.

Since the sixteenth century, Native Americans in Georgia had been contending with European colonization. Among those native groups were the Cherokees, who by the early 1800s had developed a written language and established a capital in New Echota, in what is today Gordon County. In February 1828, the Cherokees began publishing the Cherokee Phoenix, the first Native American newspaper published in the United States.

The paper circulated nationally from their capital and included columns in both English and Cherokee languages. Editor Elias Boudinot employed a strong editorial style that advocated for the rights of Cherokee people over the impositions of the American government. The publication’s title changed to the Cherokee Phoenix and Indians’ Advocate in 1829 to reflect its coverage of news and issues related to native groups outside of the Cherokee Nation. After the American government ceased making promised payments to the Cherokee Nation for the use of their land, the Cherokee Phoenix and Indians’ Advocate lost its funding and stopped printing in May 1834. The American government expelled the Cherokee people from their homes in 1838, relocating them to the Indian Territory in modern-day Oklahoma, along what is commonly referred to as the Trail of Tears.

Newspapers in Antebellum Georgia

As the state grew in both territory and population in the nineteenth century, its papers became increasingly partisan, reflecting the bitter divides in Georgia’s antebellum politics. In early nineteenth-century Georgia, political factions were split behind two feuding politicians, George Troup and John Clark.

The Troupite faction consisted largely of planters and aristocrats, while the Clarkite faction had support from small farmers and frontier settlers. Along this divide, rival newspapers formed in Georgia’s larger cities.

At the state capital in Milledgeville, the Troup-affiliated Southern Recorder opposed the Clark leanings of the Federal Union. In Macon, the Georgia Messenger was the Troupite paper and the Macon Telegraph aligned with the Clarkites; similar journalistic divisions existed in Columbus, Savannah, and Augusta. These politically aligned papers publicized the bitter and sometimes violent confrontations between the factions, which, by the 1840s, had aligned with national parties: the Clark faction aligning with the Democratic Party and the Troup faction aligning with the Whig Party.

Despite their sometimes bitter feuds, Georgia’s antebellum papers shared an ironclad commitment to the preservation of slavery. African American papers would proliferate in the postbellum era, as freedmen sought to organize politically and advocate for community need. But African Americans received very little coverage in Georgia’s antebellum newspapers, save for one notable exception: advertisements that offered rewards for the return of self-liberated African Americans.

These “fugitive slave ads” were a major source of income for newspaper publishers in Georgia and can be traced back to the first issue of the Georgia Gazette in 1763, which included several notices offering rewards for the return of fugitives from slavery. The purpose of the ads was to provide a description suitable for the identification and recapture of enslaved people. As a result, they often included detailed descriptions, including names, ages, physical descriptions, family members, methods of escape, skills, life experiences, and even places of birth—information that provides a valuable record of enslavement and its grisly toll. The ubiquity of these ads in Georgia newspapers demonstrates both the economic impact of slavery in the antebellum South and the widespread determination among the enslaved to experience a life free from bondage.

![[Engraving of] Geo[rge] M. Troup / J.C. Buttre](https://bunny-wp-pullzone-cjamrcljf0.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/George-Troup_001-444x400.jpg)

Civil War Newspapers

The onset of the Civil War (1861-65) in 1861 brought disruption to both Georgia and its newspaper industry, but despite the turmoil of war, print journalism continued throughout the state and provided citizens with coverage of the conflict, often in unorthodox ways.

Southern papers depended on supplies from Northern states for printing, and without those supplies, many papers ceased printing during the first year of the war. Publications that were able to survive reduced their number of pages and columns to remain in circulation. Obtaining news to print was also a challenge for publishers in Georgia and across the South, as telegraph news reports from the North were curtailed. Publishers and editors in Georgia remained committed, however, and often relied on correspondence from participants, and some reporters even visited the war front themselves.

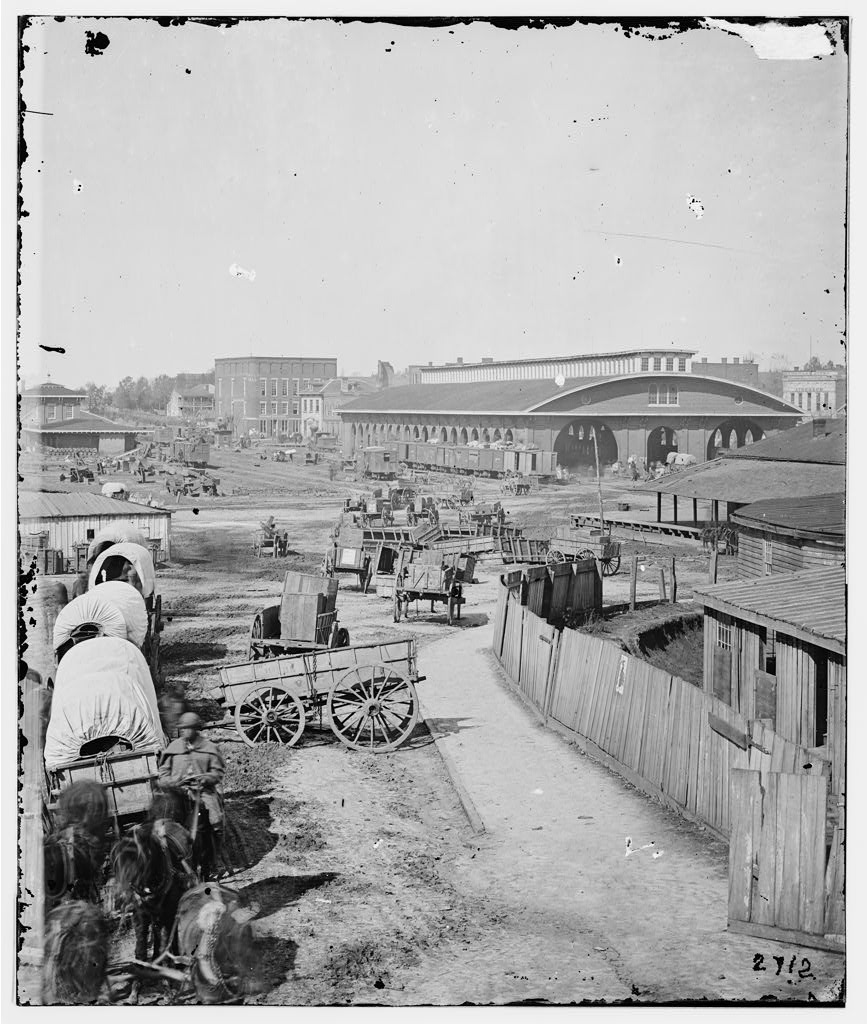

Their coverage quickly abandoned the unity that had existed behind secession, as many editors began to question the wisdom of continuing the war. In the later years of the conflict, newspaper publishing became increasingly difficult as supplies continued to dwindle, employees enlisted to fight, and mail services became expensive and unreliable. As the war front moved further south, refugee newspapers from other Southern states, including the Daily Chattanooga Rebel and the Memphis Daily Appeal, temporarily set up shop in Atlanta, which had become a commercial center during the war. In 1864, publishers in the path of Sherman’s march were forced to flee and often hid their printing equipment to avoid its destruction. The newspapers that managed to survive the end of the war and resume publication would have to adapt to a “New South” in the postwar years.

Newspapers in “New South” Georgia

At war’s end, Georgia faced physical destruction, financial turmoil, and federal occupation. Publishers that managed to resume printing in the late 1860s faced censorship and sometimes closure for their opposition to Reconstruction. Newspapers aligned with the Republican Party, however, thrived in this environment. With support from the government, pro-Reconstruction publishers established newspapers in most of Georgia’s major cities, including the Daily Press in Augusta and the Daily New Era in Atlanta.

When the Democratic Party regained control of the state government in the 1870s, Georgia’s newspaper publishers were once again free to exert editorial reign over their publications, and many of the Republican-aligned papers ceased operations. In the mid-1870s, Atlanta newspaperman Henry Grady emerged as the “spokesman of the New South,” an invigorated region that sought to lure northern investment and industry to an economy that had long been dominated by agrarian interests. As managing editor of the Atlanta Constitution, Grady advanced a pro-industrial agenda and promoted Atlanta as an ideal city for industrial growth. His advocacy resulted in the establishment of the Georgia Institute of Technology in the late 1880s, and the city hosted several expositions to promote industrial investment in the decades that followed, including the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition where Booker T. Washington delivered his “Atlanta Compromise” speech.

Grady’s “New South” was also a vision of white supremacy, however, and if African Americans wanted a voice in the burgeoning state, they would have to challenge the establishment, including the white-owned print journalism industry. While papers like Frederick Douglass’ North Star were published in northern states during the antebellum period, there is no evidence of an African American press before the Civil War in Georgia. The end of the war and the implementation of Reconstruction policies in southern states, however, led to new freedoms for the formerly enslaved, including the ability to vote and serve in elected offices.

It was in this environment that African Americans began establishing newspapers in Georgia. Among the earliest were the Colored American and the Loyal Georgian in Augusta and the Freemen’s Standard in Savannah. In 1875 John H. Deveaux established the most successful African American newspaper in nineteenth-century Georgia, the Colored Tribune. The paper, which became the Savannah Tribune in 1876, was established to promote “the rights of the colored people, and their elevation to the highest plane of citizenship…. [A]ll other considerations shall be secondary.” Nevertheless, the end of Reconstruction in 1877 allowed for increasing restrictions on African American rights, and the following year, the Tribune ceased publication after white printers in Savannah refused to produce it. Deveaux resumed publication in 1886, and the Savannah Tribune remained in publication into the twentieth century, when other African American newspapers began circulation in Atlanta, Columbus, Macon, and throughout Georgia.

Expansion, Consumption & Modernization

The Black-owned papers that emerged at the end of the nineteenth century were but one segment of a growing and diversifying industry. The state also saw a dramatic increase of weekly newspapers in the decades following the Civil War. In 1869, there were 59 weekly papers circulating in Georgia. By 1890 that number had ballooned to 225. Much of that growth occurred in south Georgia, where small-town papers began circulating in Valdosta, Waycross, Blackshear, Douglas, and elsewhere.

Due to the absence of intra-city rival publications, many of these smaller weekly papers were less politically aligned than their larger city counterparts and devoted more space to local news. Content in these newspapers usually reported local personal items, including illnesses, vacations, club meetings, church events, and humorous incidents, similar to social media posts in the twenty-first century. Their subscribers were often farmers by trade, and the average reader could also find an abundance of agricultural stories in the pages of their rural weekly papers. Many of the weeklies established during this period became the legal organs for their counties and are still in print today, including the Henry Herald, Calhoun Times, and the Jackson Progress-Argus.

Growth only continued in the twentieth century and by 1917, Georgia could boast 35 daily newspapers and 275 weekly newspapers—more than any other southern state. This expansion also included specialized newspapers intended to serve more targeted audiences, including student papers that covered events on campuses statewide. Publishers also established newspapers like the Southern Israelite, which served the Jewish population in Atlanta, to report on the affairs of religious minorities in the state. African American newspapers also expanded their presence in Georgia, among them the Atlanta World (later Atlanta Daily World), established in 1928.

Expanding technologies further contributed to a diversified readership, as publishers were increasingly able to afford a variety of new features, including illustrations, photography, and cartoons. But the biggest change during this period may have been the increasing prominence and sophistication of advertisements.

After the Civil War, the effects of the Second Industrial Revolution resulted in the increasing presence of advertisements for manufactured goods in the state’s newspapers. At the same time, the development of national newspaper advertising agencies increased the availability and importance of advertising dollars to newspaper publishers. By the 1920s, the country was experiencing unprecedented prosperity. Increasing levels of disposable income coupled with cheaper manufactured products resulted in a consumer culture that fueled changes in the content of newspaper ads. A newspaper subscriber in Georgia could find ads for cars, soft drinks, phonographs, and vacations nestled alongside their local news. With expanding page counts, there was space for increasingly larger ads to catch the reader’s attention. As the United States progressed through the Great Depression and World War II (1941-45), the purchasing behaviors of Americans changed, but advertisements in Georgia’s newspapers maintained the conspicuous style that rose to prominence in the early twentieth century.

Yellow Journalism

One of Georgia’s most notorious newspapers, the Atlanta Georgian, began publication in the early twentieth century. Along with editor John Temple Graves, Fred Loring Seely established the daily publication in 1906 to compete with the city’s two leading papers, the Atlanta Constitution and Atlanta Journal. During its first months of publication, the paper prominently featured unsubstantiated stories of Black men attacking white women. The coverage inflamed racial resentment among the city’s white population and resulted in the Atlanta Race Massacre in September 1906. Over a three-day period, mobs of white men assaulted hundreds of Black men, murdered dozens, and vandalized Black-owned businesses and homes.

Newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst purchased the paper in 1912. Under his son’s leadership, the paper adopted the practices of “yellow journalism,” including large headlines, extensive use of photography, and loose journalistic standards. The purpose of these sensationalist practices was to attract reader attention and increase sales. The Georgian employed these tactics in an attempt to commercialize the 1913 Leo Frank murder trial, sometimes publishing as many as eight editions in a single day. In 1924, the paper employed trailblazing journalist Mildred Seydell, who covered the Scopes Trial and wrote for the Georgian’s society page. James M. Cox purchased both the Georgian and the Journal in 1939 and dissolved the Georgian shortly thereafter.

Civil Rights

With its blatant fearmongering and reckless reporting, the Georgian highlights the dangers posed by an unscrupulous press. But newspapers could be a force for social justice, too, as the state’s civil rights era publications showed. In the 1950s and 1960s, Georgia was home to some of the most prominent movement leaders at the time, including Martin Luther King Jr., Coretta Scott King, Hosea Williams, and Julian Bond. Organized protests in Atlanta, Albany, Americus, and countless other cities brought attention to the cause and were covered by newspapers throughout the state.

While not all papers were supportive of the movement, Georgia’s press corps included prominent reform-minded columnists such as the Atlanta Constitution’s Ralph McGill and Gene Patterson, who won Pulitzer Prizes for their editorials in 1959 and 1967, respectively. The African American press and school newspapers also reported on civil rights activities, providing readers with more personal and distinctive coverage of the events in Georgia’s cities and college campuses. Black activists and entrepreneurs meanwhile established newspapers in many of Georgia’s larger cities. One of the earliest and most prominent of these publications was the Atlanta Inquirer. Participants in the Atlanta Student Movement founded the Inquirer in 1960 in response to the conservatism of the city’s other Black-owned newspaper, the Atlanta Daily World. The pages of the Inquirer covered the events of the movement and supported the fight for racial equality in Atlanta and throughout the South. Early reporters for the paper included future state Senator Leroy Johnson and Charlayne Hunter-Gault, who integrated the University of Georgia with fellow student Hamilton Holmes.

The fight for rights and freedoms was also taken up by other historically oppressed groups in the second half of the century, resulting in the Women’s Liberation Movement, the Chicano Movement, the Gay Rights Movement, and the American Indian Movement. Their voices were often heard in the pages of Georgia’s alternative press, which allowed activists to communicate and connect through the time-honored tradition of print journalism.

Georgia Newspaper in the Information Age

Beginning in the second half of the twentieth century, newspapers began the most dramatic transformation in the history of the industry. Georgia newspapers started a long process of consolidation in the 1950s, as national corporations purchased daily newspapers in cities across the state and merged intracity papers.

Even more substantial change came with the emergence of computer-based technologies. These innovations changed both how newspapers produced their content and how readers consumed it. By the century’s end, Georgia newspaper publishers large and small began to abandon long-standing technologies in favor of a more computerized process for producing newspaper content.

The growth of information technology also changed the manner in which people consumed news. The advent of the World Wide Web in the 1990s generated a new demand for online news content and newspaper publishers responded by hosting their own websites to accompany their print editions. A decrease in print newspaper subscriptions in the decades that followed, combined with the increased popularity of online news sources, led many Georgia newspapers and newspapers across the country to monetize their online content by offering online subscriptions and digital editions of print issues. As technologies and behaviors continue to change in the twenty-first century, so too will the approach of delivering news in Georgia and around the world.

![[Engraving of] Geo[rge] M. Troup / J.C. Buttre](https://bunny-wp-pullzone-cjamrcljf0.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/George-Troup_001.jpg)