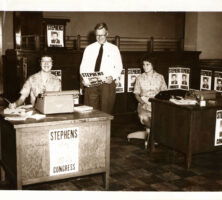

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries

On the Stump: What Does It Take to Get Elected in Georgia?

This exhibition invites you to step into the shoes of a candidate and onto the campaign trail. We’ll follow candidates as they decide to run, craft a strategy, win nominations, shake hands, kiss babies, and await the election results.

Introduction

On the Stump considers the evolution of campaigning for political office in the state, from the passage of the white primary in 1900 to the presidential election of 2012. The exhibition invites visitors to step into the shoes of a candidate and onto the campaign trail. We’ll follow candidates as they decide to run, craft a strategy, win nominations, shake hands, kiss babies, and await the election results.

Consider at once the social, cultural, and political history of a state in motion. Meet the changing cast of characters who have shaped and reshaped the style, strategy, and substance of political life and culture in Georgia. How have politicians and the public that elects them changed over time?

This exhibition was developed in 2016 by the Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies at the University of Georgia in Athens.

Deciding to Run

A passion for public service, a call to family tradition, a commitment to pressing issues of the time, or personal ambition—all have fueled a desire to run for public office. Even as the issues and approaches to campaigning in Georgia have grown more complex, the core motivations for potential candidates have remained relatively unchanged.

Georgians considering a run for elected office in the first decades of the twentieth century decided by talking with family, friends, and prominent people in the community. Some, like the Russells or Talmadges, grew up in political families and received advice and encouragement from relatives about continuing the family business of public service. Campaigning in those days was a relatively straightforward proposition of establishing a strong network of friends and neighbors in various Georgia counties. Fifty years later, as Georgia’s electorate has grown larger and more diverse, mounting a successful political campaign has become a complex proposition. Politicians not only have transitioned to new media to connect with potential voters but also now hire professional operatives to conduct opinion polls and consult with state and national party leaders to gauge broader interest and support. These new sources of information often shape the final decision of when and how to run a campaign.

Candidates running for office in 2016 throw their hats into the ring for many of the same reasons as their counterparts did a century ago. Every political story, great and small, begins with the critical decision to run.

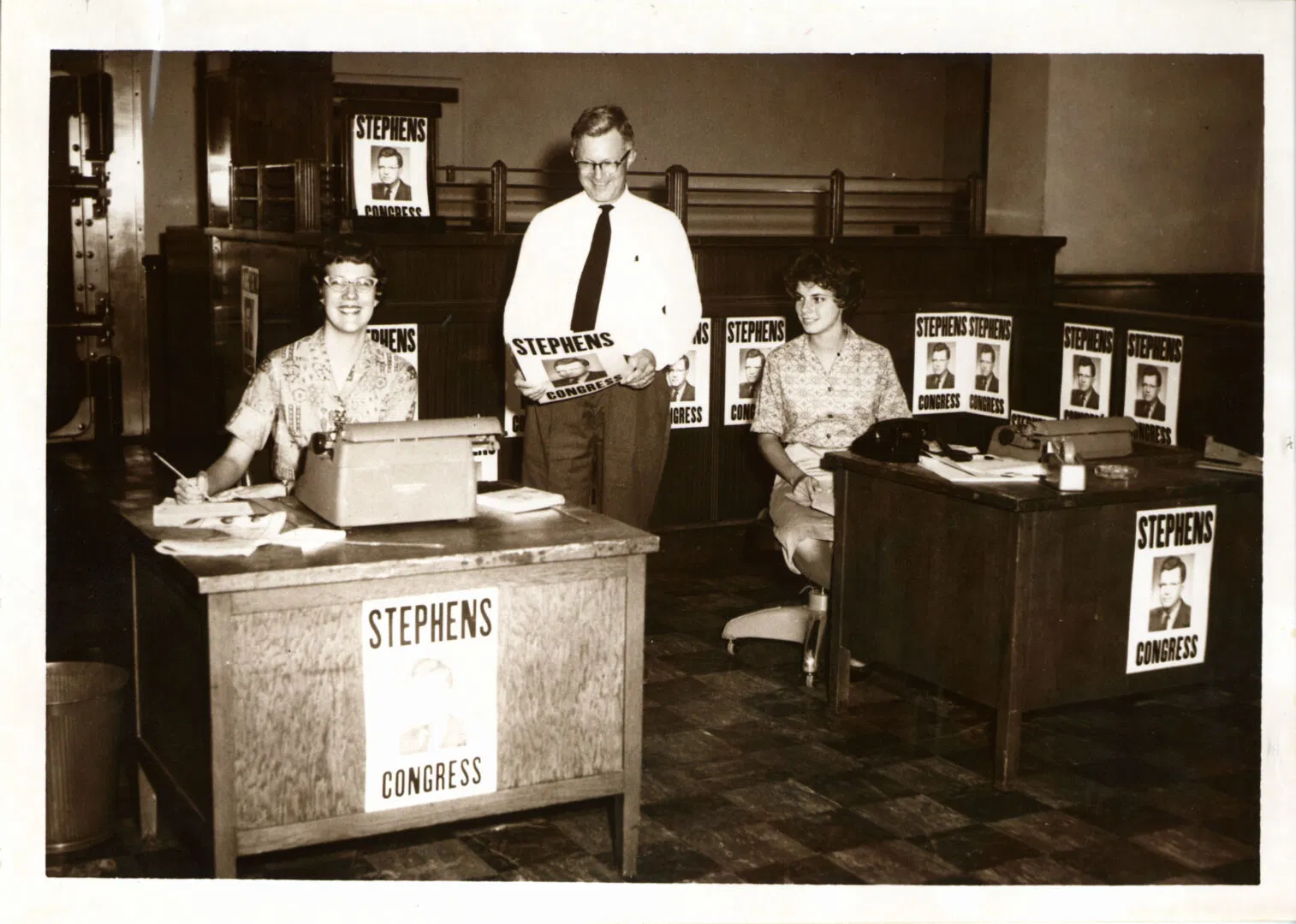

Gathering Support

Dan Hughes spent the spring of 1908 at his desk firing off letters to friends and acquaintances across Georgia’s Third Congressional District. His goal: find a strong supporter in each precinct to help elect his father, Dudley, to the U.S. Congress. Like any good campaign manager, he promised a steady stream of platforms and handbills for distribution, along with help obtaining coverage in the local press. He knew, though, that a truly successful campaign required locally influential supporters willing to “talk Hughes” at every opportunity. In an era before radio, television, or good roads, gathering support for a political campaign lived and died by friendships, the newspaper, and the U.S. Postal System.

A candidate’s family members and friends created the foundation of a campaign. Membership in social, civic, and religious organizations also offered access to would-be constituents and potential forums for political speechmaking. Perhaps most crucial was securing the backing of small-town political power brokers—figures who could use their influence to mobilize and deliver votes in small, rural counties.

Fight for the Franchise

In the years after Reconstruction, the Democratic Party practically monopolized Georgia’s political system by enacting legislation that restricted ballot access and discouraged support for alternative political parties. Perhaps the single most effective mechanism for ensuring Democratic dominance was the “white primary.” Established formally in 1900, this practice excluded the vast majority of African Americans from the political process. Without effective political opposition in general elections, winning the whites-only Democratic primary became “tantamount to election” in Georgia. The white primary remained standard across the South until the mid-1940s, when the United States Supreme Court’s landmark Smith v. Allwright (1944) ruled it unconstitutional. Columbus native Primus King, an African American voter who was denied access to the polls during the 1944 Democratic primary election, lodged a subsequent legal challenge against the Muscogee County Democratic Executive Committee. Decided in 1946, Chapman v. King helped close legal loopholes that remained in the wake of the Smith case.

Although the Smith and King decisions lifted one restriction on Black franchise, other hurdles remained. Georgia’s county unit system, which the U.S. Supreme Court abolished in the 1962 Baker v. Carr decision, favored voters in thinly populated rural counties where African American disfranchisement was almost absolute. Until it was overturned, the county unit system allowed politicians to focus primarily on rural counties to win statewide office.

On a national level, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 effectively banned all racial discrimination in voting. It is still considered one of the civil rights movement’s greatest legislative victories. Along with population growth in metropolitan areas, court-mandated redistricting, and the development of mass media outlets, these transformations shifted political power away from the countryside and to the more diverse and populous cities and suburbs. The presidential campaigns of Republicans Barry Goldwater in 1964 and Ronald Reagan in 1980 added another layer of complexity by boosting the development of a two-party system in Georgia. Ultimately, these complex changes reshaped the campaign trail in Georgia as contenders for public office fought to keep pace with an expanding electorate.

Developing a Platform

In his 1906 campaign platform, gubernatorial candidate Hoke Smith addressed only a handful of items—among them were his support of white supremacy, railroad reform, and an end to political corruption. Structures like the white primary and the county unit system enabled candidates to narrowly focus on a primarily white, rural audience when campaigning. This permitted them to stray from the national party line and to prioritize local issues. Candidates in this period constructed their campaign platforms on the key issues that mattered most to one demographic.

As legislative changes broadened constituencies in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, campaigns became more professional, and the scope and expectations of the platform increased dramatically. Rather than a simple statement of ideals, candidates began investing time and resources into taking the pulse of the electorate—researching key issues and carefully wording public messages for targeted appeal. Meanwhile, at campaign appearances candidates stuck to a few bulleted statements that made them most identifiable to voters. Developing a platform became a branding process, distinguishing one candidate from the next in both style and substance.

In his reelection bid for governor in 1994, Zell Miller drew little inspiration from the limited approach of Hoke Smith. He offered constituents a book-length platform of in-depth research conducted on every issue from drug abuse to education, health care to the environment. A team of experts and campaign consultants crafted each position statement and calculated the cost for proposed programs. Today, the campaign platform may begin as a sketch of ideals and pledges expressing a candidate’s values, but it is molded into a document of compromise by voter demands, the party line, special interest groups, and the prevailing political and economic climates. Strong enough to win broad public support without abandoning core values and constituencies, the platform attempts to strike a delicate balance.

Joining the Party

Candidates who manage to secure their political party’s nomination can usually count on considerable support in the post-primary election season. Parties assist with campaign training, fundraising, research, communications, and voter mobilization initiatives. Only recently, however, have party resources reached something near equality in Georgia. After James M. Smith took the governor’s mansion from the Republican Party in 1872, Georgia Democrats did not relinquish control until 2003. Indeed, for almost a century, the Democratic Party of Georgia reigned virtually unchallenged while law, culture, and custom prevented the development of a two-party political system.

Democratic domination of Georgia politics began faltering in the 1960s as the national party grew increasingly liberal on economics and civil rights while the Republican Party embraced the modern conservative movement. These political shifts, as well as prolonged in-migration of northern Republicans to Georgia’s fast-growing cities and suburbs during the mid-twentieth century, reinvigorated the GOP in Georgia. The Republicans’ careful organization, alignment with pro-business policies, and alliance with culturally conservative, evangelical Christians made the party a force to be reckoned with by the 1990s.

Today, demographic shifts are once again altering Georgia’s electorate. The number of registered Hispanic and Asian voters in the state is on the rise. Exit polls from recent statewide elections indicate disproportionately large minority voter participation, and projections suggest white voters will no longer compose a majority of the state’s electorate by 2040. Whether or not these trends continue and produce more diverse candidates remains to be seen.

Redistricting

The U.S. Constitution mandates a once-per-decade federal census to determine the number of people living in each state. The 435 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives are apportioned among the 50 states based on these findings. Owing to the domination of a single political party, Georgia did not dramatically alter its congressional districts between 1931 and 1964. The relative lack of redistricting was a key strategy in helping small rural populations elect conservative white candidates. In response to the Voting Rights Act (1965), maps began to reflect growing urban populations and, eventually, to ensure the creation of districts favorable to minority candidates. Even today there is no law banning partisan redistricting, leaving the state General Assembly able to redraw lines benefiting the party in power.

More than gathering support or fundraising, many potential candidates now look to redistricting schedules and maps years in advance of a run for office. New technologies help size up potential success with the changing demographics of a district, pushing some to relocate or wait out shifting populations before tossing their hat into the ring.

Planning a Strategy

In the 1950s, it was said that all a candidate needed to get elected in Georgia was political boss Roy V. Harris and $50,000. In 2016 candidates rely on dozens of staffers, a medley of rural and urban counties, and so-called Super PACs, which can accept nearly unlimited donations to run positive and negative advertising on candidates’ behalf. Campaigning has grown from a small-scale affair requiring a few influential people and some modest investment to an enterprise that demands extensive planning, expert management, and vast sums of money to give a candidate a chance for victory.

In the South, office seekers molded strategy around the structures that upheld the one-party system—the white primary, poll tax, and in Georgia, the county unit system. Coupled with intimidation and the threat of violence, these fixtures ensured that African Americans remained largely absent from elections in the state. An entrenched white power structure controlled elections on the local and state levels until the early 1960s.

Political developments in the 1950s and 1960s—white southern resistance to federal civil rights legislation, increased participation of minority groups, the revival of the Republican Party, and new technologies—compelled campaigns to deal with newly powerful voting groups. To better navigate and benefit from these diverse constituencies, politicians began using polling data. They hired publicists and consultants to devise the format and character of advertisements, plot campaign routes and personal appearances, and defuse attacks launched by opponents. Today, candidates increasingly rely on media outlets—radio, television, and the Internet—to project a well-crafted image to the public. These new methods have become essential to extending the personal reach of a candidate to growing numbers of voters.

Harnessing New Media

Radio reshaped American political discourse. The medium enabled candidates to appeal directly to a wider audience, and by the 1940s major political parties increasingly purchased transmission time on national networks each campaign season. A candidate’s radio voice became a crucial part of his or her persona. Party promoters shrank from nominees who lacked the charisma and charm of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Radio forced candidates to think fast, talk faster, and stick to a simple message.

Expansion of coaxial cables and microwave transmissions in the 1950s made television the next political frontier. In Georgia’s 1950 gubernatorial race, Democrats Herman Talmadge and Melvin E. Thompson relied on newspaper and radio advertisements to lobby for support. By the fall of 1952, many candidates for state office were running nightly television advertisements. In 1954 the cities of Macon, Columbus, Augusta, and Savannah boasted stations, in addition to Atlanta, and the number of households with sets continued to grow.

Today, the twenty-four-hour news cycle leaves little mystery about candidates on the campaign trail—months and even years before a given election. While candidates still use TV advertisements, an increasing number of commercials are produced exclusively for online streaming. Campaigns have also embraced social media—from Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook to YouTube and Snapchat—personalizing their appeals for votes and restoring the word-of-mouth power so important to early politicking.

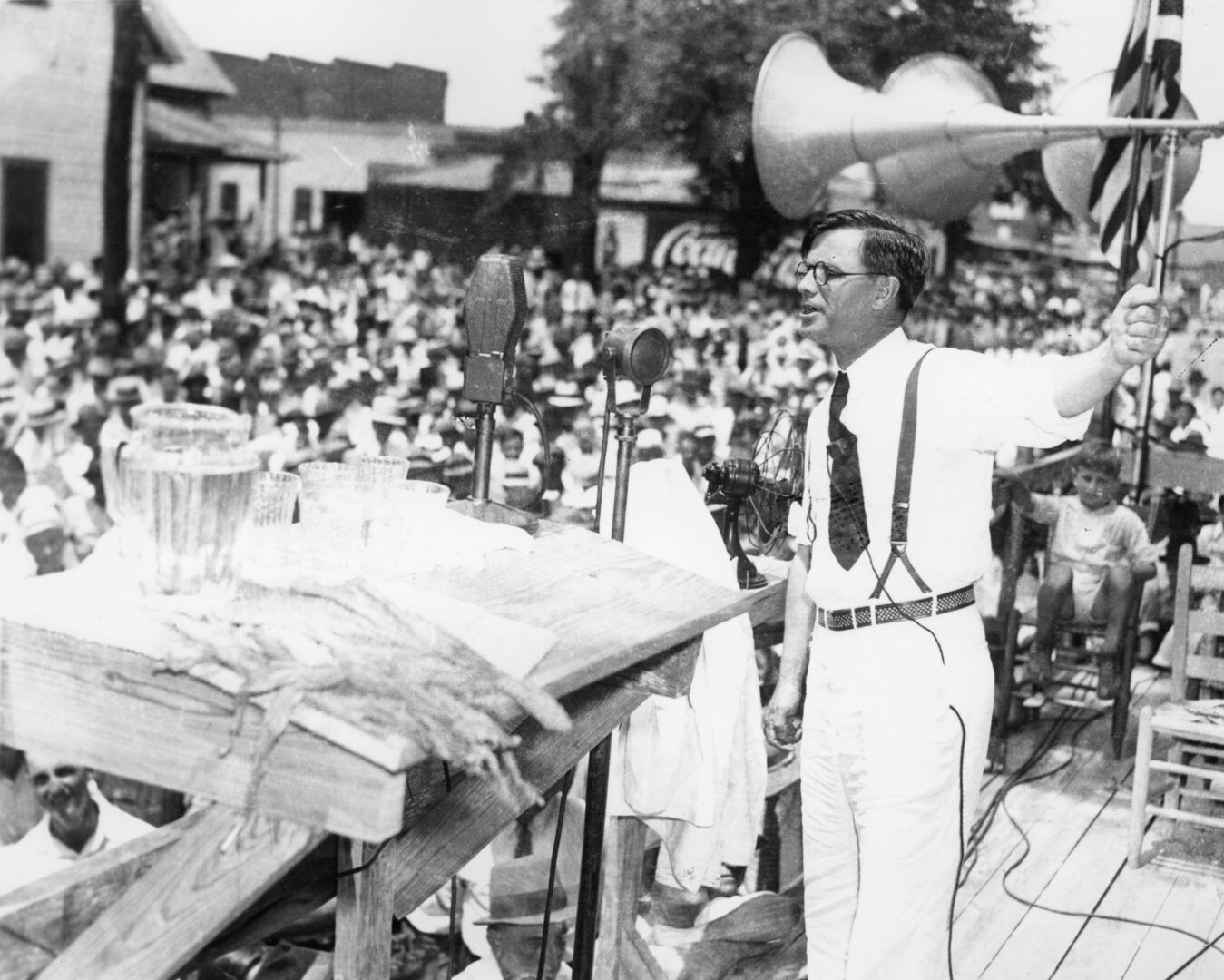

Performing on the Stump

Some who saw him on stage recalled that a speech by Eugene Talmadge was better than any show they paid to see. With a charismatic personality, plain speech, and his signature red suspenders, Talmadge was a showman seldom rivaled. Despite a middle-class upbringing and law degree, he billed himself as a “real dirt farmer” and delivered rousing oratory centered on strong support for segregation, small government, and the struggles of rural white voters. Talmadge perfected the craft of the stump speech, the standard speech repeated at each campaign stop outlining key parts of a politician’s platform, then the most fundamental way politicians connected with constituents and voters.

Shaking hands and kissing babies—these customs too echoed the need to establish a personal connection with constituents, a cornerstone of early twentieth-century political culture in Georgia. Walking miles a day to give as many speeches as possible, sending personalized mailings, participating in parades, and hosting barbeques and fish-frys filled a candidate’s calendar. From the 1950s onward, the expansion of road networks and access to radio and television extended the reach of the candidate while the distribution of mass-produced campaign gear—buttons, bumper stickers, yard signs, and T-shirts—became another popular electioneering tool.

While traditional speechmaking tours still occur, politicians today more often rely on television and the Internet to communicate with voters. The public consumes speeches piecemeal in the twenty-four-hour news cycle. Candidates continue to search for and adopt new formats allowing them to establish that personal connection with growing numbers of diverse voters in an increasingly digital world.

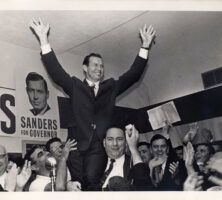

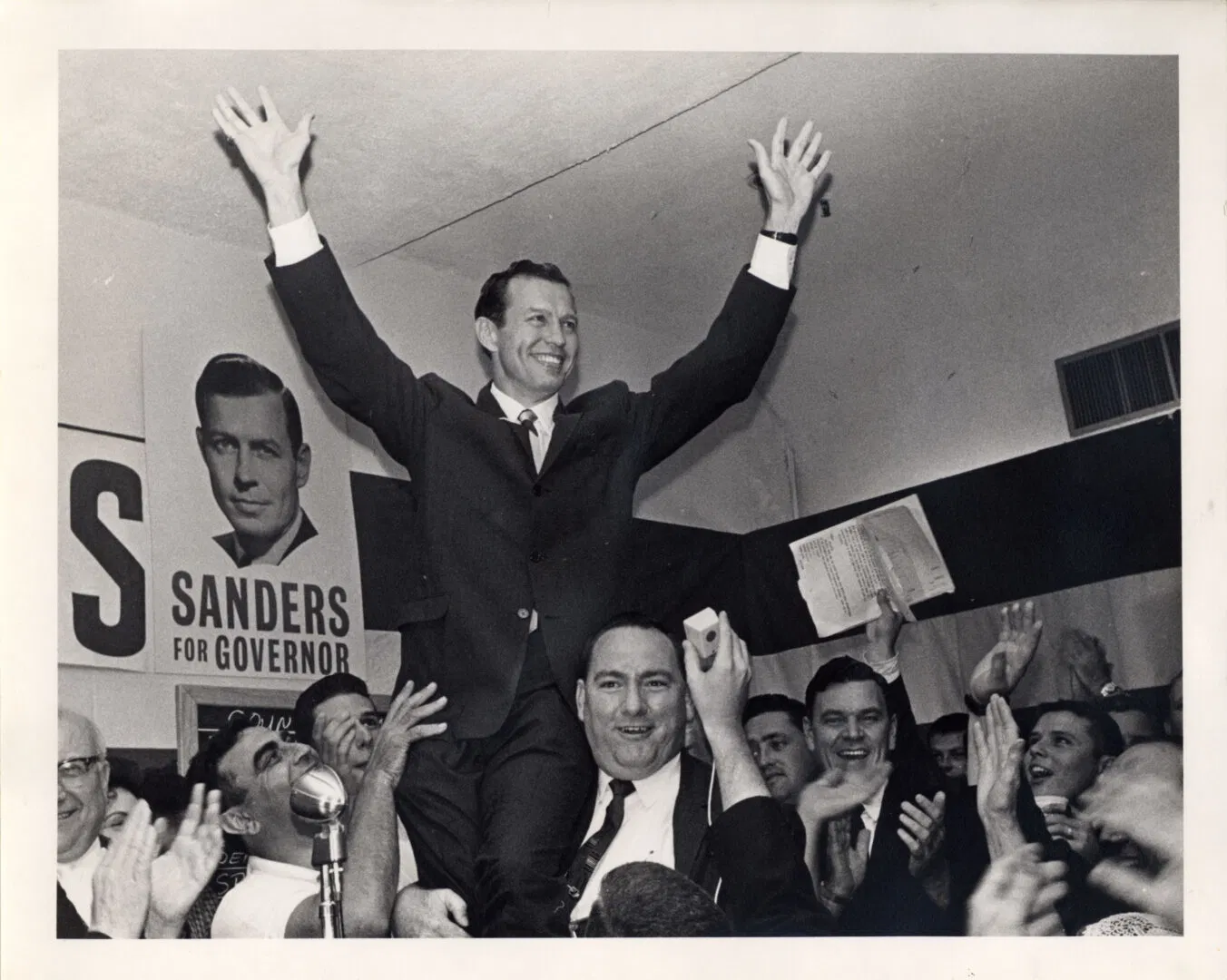

Awaiting the Results

After months, and sometimes years, on the campaign trail, candidates reach an emotional finish line on election night. Some host festivities with their supporters at campaign headquarters, while others await the returns quietly with family and friends. They hope for victory and fear defeat, but are sometimes granted neither.

In 1946 Georgians elected Eugene Talmadge to succeed progressive up-and-comer Ellis Arnall as governor. Talmadge was in poor health, though, and his inner circle feared he might not live to be sworn into office. Capitalizing on a loophole in the state constitution empowering the General Assembly to appoint a new governor from runner-up candidates in the event of the governor-elect’s death, the Talmadge machine quietly ran Eugene’s son Herman as a write-in candidate in the general election. With no Republican on the ballot, and a fortuitous discovery of additional write-in votes from his home county, the younger Talmadge placed second with just 675 votes. Eugene Talmadge died on December 21, 1946.

Legislators prepared to replace the governor-elect with his son just as another claimant stepped forward: M. E. Thompson, the newly elected lieutenant governor. Thompson felt he should assume the governorship, but as lieutenant governor was a new state office, the constitution made no such provision. The General Assembly voted to elect Herman Talmadge, and Thompson filed suit. Meanwhile, Ellis Arnall refused to leave office until a successor was legitimized. After two months of tumult, the state Supreme Court ruled in favor of M. E. Thompson. Herman Talmadge exacted political retribution when he defeated Thompson in a hotly contested special election held in 1948 to fill the remaining two years of the term.

Georgia politicians and voters were again left hanging after Election Day in 1966. U.S. Representative Howard “Bo” Callaway made history as the first Republican to place first in a Georgia gubernatorial race in nearly a century, gaining 46.5 percent of the vote. Democrats split their votes between Lester Maddox, a staunch segregationist, and Ellis Arnall, a write-in candidate. Because no candidate received more than fifty percent of the vote, it was up to the Georgia Assembly to vote on Georgia’s next governor. Most of the legislators were Democrats, and most had signed a loyalty oath to support the Democratic candidate. Even though many of the legislators saw Maddox as an extremist, they were bound to vote for him. Maddox won the house vote and, with it, his first election.

Evolving Campaigns

Democracy in the United States has evolved since its birth to reflect changes in public attitudes, enfranchisement, technology, the economy, and more. Presidential politics has most often paved the way for trends at the state and local level.

The formation of a two-party system during George Washington’s second term launched such traditions as newspaper endorsements and paid campaign surrogates in subsequent elections. The 1840 race between Martin Van Buren and William Henry Harrison was among the first to introduce stump speeches along with partisan rallies and campaign ephemera. Radio advertising began in earnest during the 1930s, followed by television some twenty years later. By the 1960s, campaign politics was an increasingly professionalized cottage industry, with paid media consultants and in-house polling. Today, the explosion of Internet-based politicking, from blogs to online fundraising, ads, polling, and publicity stunts is the new frontier.

Where do you think electoral politics will go next?