The tumultuous political and social change in Georgia during the 1960s yielded perhaps the state’s most unlikely governor, Lester Maddox. Brought to office in 1966 by widespread dissatisfaction with desegregation, Maddox surprised many by serving as an able, though unquestionably colorful, chief executive.

Early Years

Born in Atlanta to a working-class family on September 30, 1915, Lester Garfield Maddox grew up in poverty. By 1933 he had dropped out of high school and was working at Atlantic Steel and the Works Progress Administration. In 1936 he married Virginia Cox, with whom he would remain for sixty-one years, until her death in 1997. During World War II (1941-45) Maddox worked in various wartime industries, including the Bell Bomber factory in Marietta, receiving an essential-occupation draft deferment. Frequently disgusted by what he perceived as widespread inefficiency and waste in war production, Maddox quit his job in 1944 and sought to achieve the American dream through entrepreneurship.

The Pickrick

In 1947 Maddox opened his most enduring and successful enterprise, the Pickrick Cafeteria. Located in Atlanta at 891 Hemphill Avenue, the Pickrick offered home-style fare near the campus of the Georgia Institute of Technology. In 1949 Maddox ran the first of his “Pickrick Says” advertisements in the Atlanta Journal. Through the voice of “Pickrick,” Maddox’s fictional alter ego, these advertisements promoted the culinary offerings of the restaurant with a generous helping of the proprietor’s homespun political commentary. Through these ads Maddox created a forum for anxieties shared by white working-class Atlantans, mostly over the issues of segregation and governmental corruption. The popularity of Maddox’s sometimes pointed and combative monologues led to his emergence as a public figure.

Entry into Politics

In 1957 Maddox decided to put his words into action and challenged the incumbent, William B. Hartsfield, in the Atlanta mayoral race. Maddox was unsuccessful. Four years later he lost again to Ivan Allen Jr. In both campaigns he championed integrity and economy in government—and above all else, segregation. Undeterred by these setbacks in city politics, Maddox entered the 1962 lieutenant governor’s race, only to suffer a runoff defeat against fellow segregationist Peter Zack Geer. By 1962 Maddox believed a political career was not meant to be.

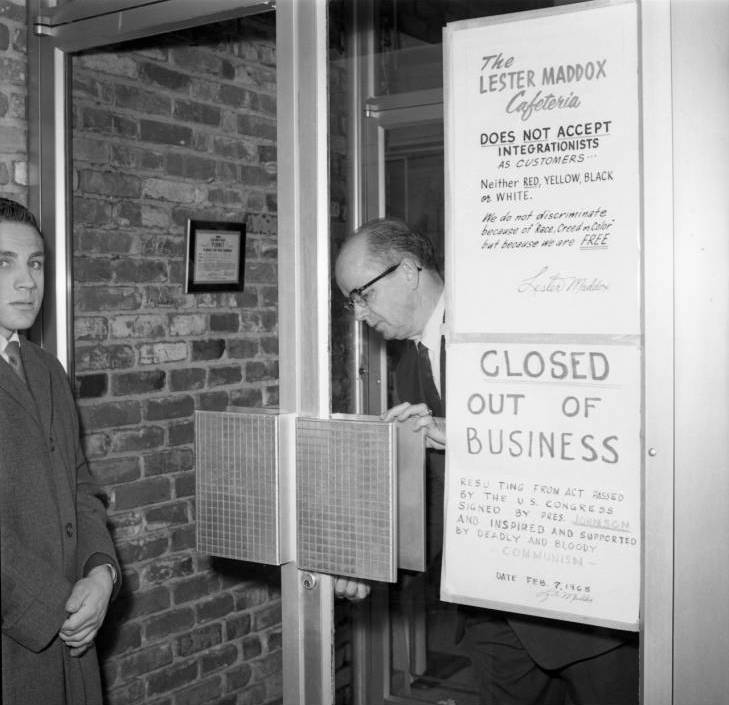

Although many Atlanta businesses had desegregated before the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Maddox’s Pickrick remained stubbornly wedded to the segregationist Jim Crow policies. The passage of the act put Maddox on a collision course with the “forces of integration” he so ardently opposed. As a conspicuous symbol of segregationist defiance, the Pickrick became an immediate target of civil rights activists seeking to test the new law.

On July 3, 1964, Maddox and a throng of supporters wielding axe handles forcibly turned away three Black activists. A photograph of the scene ran on the front pages of newspapers across the nation, creating an image of Maddox as a violent racist. Maddox would both shun and cultivate this reputation at various points throughout his career. After losing a yearlong legal battle in which he challenged the constitutionality of the public accommodations section of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Maddox elected to close his restaurant rather than desegregate.

Maddox’s stand at the Pickrick endeared him to many white Georgians who remained unwilling to relinquish segregation. Riding a wave of reaction to the Civil Rights Act, Maddox entered Georgia’s 1966 gubernatorial contest and shocked many political observers by defeating the liberal former governor Ellis Arnall in the Democratic primary. This victory set the stage for a hard-fought campaign against textile heir Bo Callaway, the first credible Republican candidate for governor since Reconstruction. In a bizarre turn of events, Callaway won the popular vote, but because of a write-in campaign for Arnall, the Republican lacked a majority of votes. Following the Georgia constitution of the day, the legislature, controlled by Democrats, decided the election in favor of Maddox.

Maddox as Governor

Rumors that Maddox would return Georgia to a state of massive resistance against segregation proved unfounded. In fact, Maddox proved reasonably progressive on many racial matters. As governor he backed significant prison reform, an issue popular with many of the state’s African Americans. He appointed more African Americans to government positions than all previous Georgia governors combined, including the first Black officer in the Georgia State Patrol and the first Black official to the state Board of Corrections. Though he never finished high school, Maddox greatly increased funding for the University System of Georgia.

Maddox’s term was not without controversy, however. Fearing riots during the funeral procession of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, Maddox overreacted with a heavy-handed police presence. He also refused to order flags at state facilities to be lowered to half-mast for the funeral. As the leader of the state’s delegation to the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago, Illinois, Maddox fought against the civil rights aims of the party.

Despite such conflict, Maddox remained a popular governor with many of Georgia’s citizens, paradoxically including many African Americans. He instituted such populist ideas as “Little People’s Day,” when average citizens could line up to meet with the governor twice a month at the Governor’s Mansion on West Paces Ferry Drive in Buckhead.

After the Governorship

Constitutionally unable to succeed himself as governor in the 1971 election, Maddox ran for and became the state’s lieutenant governor. During his term he often found himself at odds with his political rival, Governor Jimmy Carter. He unsuccessfully ran again for governor against George Busbee in 1974 and in several elections thereafter. Maddox also ran for president of the United States as an independent in 1976. Returning to private life, Maddox operated a furniture store and a variety of other enterprises, none of which proved as successful as the Pickrick. Toward the end of his life, Maddox expressed few regrets and made no apologies for his segregationist beliefs or any of his other political stances.

After enduring a long fight with cancer and a host of additional ailments, Maddox died on June 25, 2003, at the age of eighty-seven.