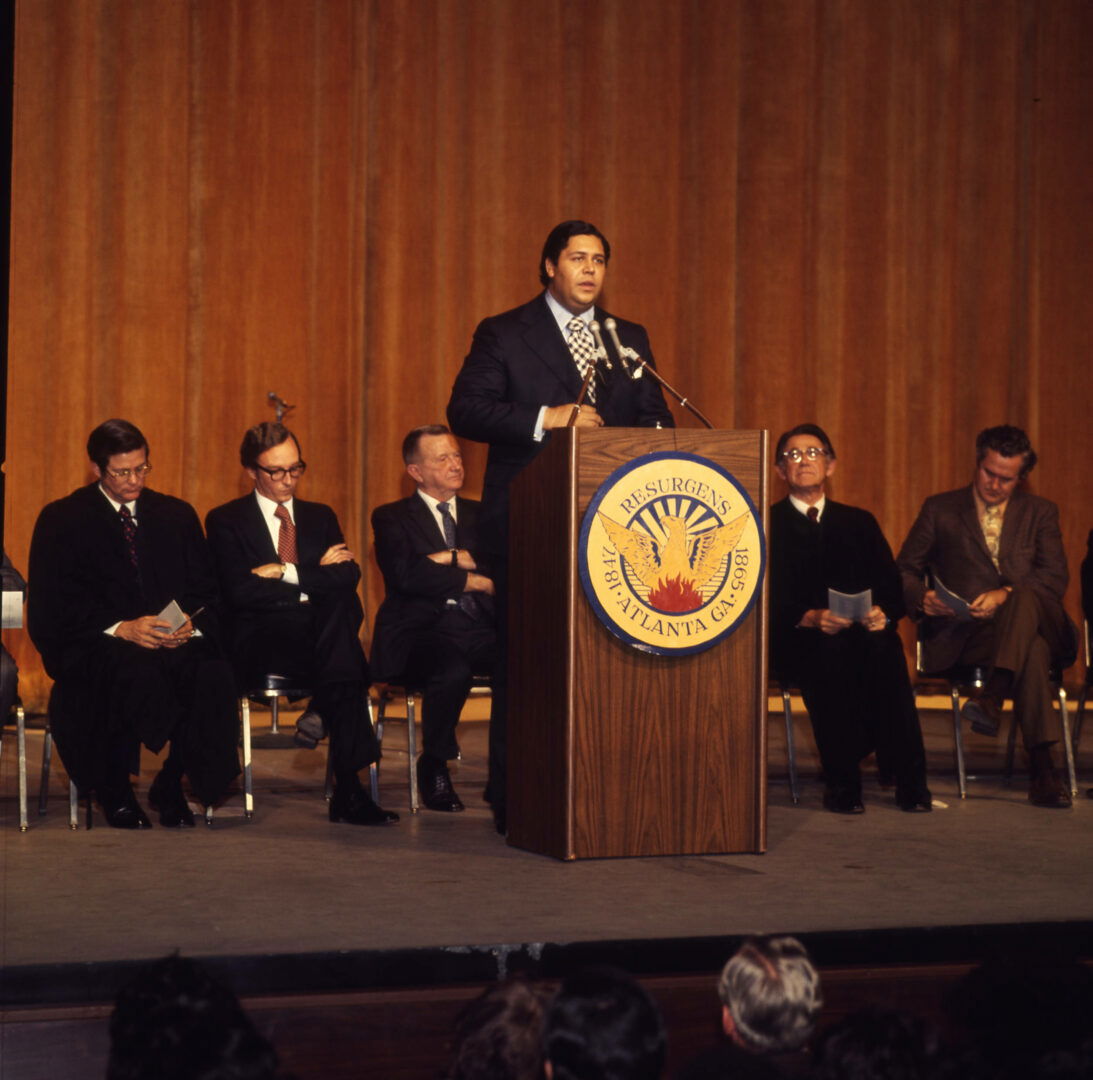

Elected mayor of Atlanta in 1973, Maynard Jackson was the first African American to serve as mayor of a major southern city.

Jackson served eight years and then returned for a third term in 1990, following the mayorship of Andrew Young. As a result of affirmative action programs instituted by Jackson in his first two terms, the portion of city business going to minority firms rose dramatically. A lawyer in the securities field, Jackson remained a highly influential force in city politics after leaving elected office. Before and during his third term, he worked closely with Young, Atlanta Olympics organizing committee chair Billy Payne, and others to bring the 1996 Olympic Games to Atlanta.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Maynard Holbrook Jackson Jr. was born on March 23, 1938, in Dallas, Texas, where his father, Maynard H. Jackson Sr., was a minister. The family moved to Atlanta in 1945, when Maynard Sr. took the pastorship at Friendship Baptist Church. Maynard Jr.’s Atlanta roots ran deep. His mother, Irene Dobbs Jackson, a professor of French at Spelman College, was the daughter of John Wesley Dobbs, founder of the Georgia Voters League. When Jackson Sr. died in 1953, Dobbs became even more influential in the life of his fifteen-year-old grandson. In 1959 Jackson’s mother became the first African American to receive a card to the Atlanta Public Library, thereby integrating that institution.

Jackson entered Morehouse College through a special early-entry program and graduated in 1956, when he was only eighteen. He then attended Boston University law school but was unsuccessful. After working several jobs in the North, including one as an encyclopedia salesman, Jackson received his law degree from North Carolina Central University in 1964. In December of the following year he married Burnella “Bunnie” Hayes Burke. They had three children, Elizabeth, Brooke, and Maynard III. During the late 1960s Jackson worked as an attorney for the National Labor Relations Board and a legal services firm.

In 1968 thirty-year-old Jackson undertook an impulsive, quixotic, and underfunded race for the U.S. Senate against incumbent Herman Talmadge. Although he won less than a third of the statewide vote, he carried Atlanta and immediately became a force to be reckoned within city politics. The next year he was elected vice mayor, the presiding officer of the board of aldermen. While Jackson was serving in this role, the charter of the city of Atlanta was modified to strengthen the hand of the mayor. The new charter changed the aldermen to council members and replaced the vice mayor with the position of president of the city council.

Under Atlanta mayors William B. Hartsfield and Ivan Allen Jr., the city had developed a precedent for its elected leaders earning their positions through the support of a voting coalition of Blacks and liberal/moderate whites. Although not an Allen protege, the Caucasian Jewish real estate developer Sam Massell was elected mayor through strong African American support in the same election that made Jackson vice mayor. At that time Atlanta’s Black political leaders planned to support Massell for a second term and then seek to elect an African American in 1977, by which time the city’s electorate would be overwhelmingly Black. Jackson felt he could unseat Massell in the 1973 election, and polls demonstrated his popularity with voters. Impressed, influential African American business leaders Jesse Hill and Herman J. Russell joined Jackson’s 1973 mayoral campaign. The Massell-Jackson runoff election became racially polarized, but Jackson won with just under 60 percent of the vote and, at age 35, became the first Black mayor of a large southern city.

As mayor, one of Jackson’s main priorities was to ensure that minority businesses received more municipal contracts, and he succeeded in raising the proportion from less than 1 percent to more than 35 percent. His crowning achievement as mayor was building the massive new terminal at Hartsfield Atlanta International Airport with significant minority participation, and in his own words, “ahead of schedule and under budget.” (In 2003 the airport’s name was changed to Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport in Jackson’s honor.) Jackson’s insistence on affirmative action, his emphasis on public involvement in neighborhood planning, and a number of other issues created a rift between the mayor and much of the white business community in Atlanta.

Jackson also transformed the police department in an effort to reduce charges of police mistreatment of African Americans and to help Blacks rise in the ranks. Meanwhile, a series of murders of Black youths, known as the Atlanta child murders, terrorized the city from 1979 to 1981, and Jackson worked to maintain calm in the city until Wayne Williams was caught and convicted in connection with the crimes. Jackson later broke with his public safety commissioner, Reginald Eaves, and Eaves resigned in a promotion-exam cheating scandal.

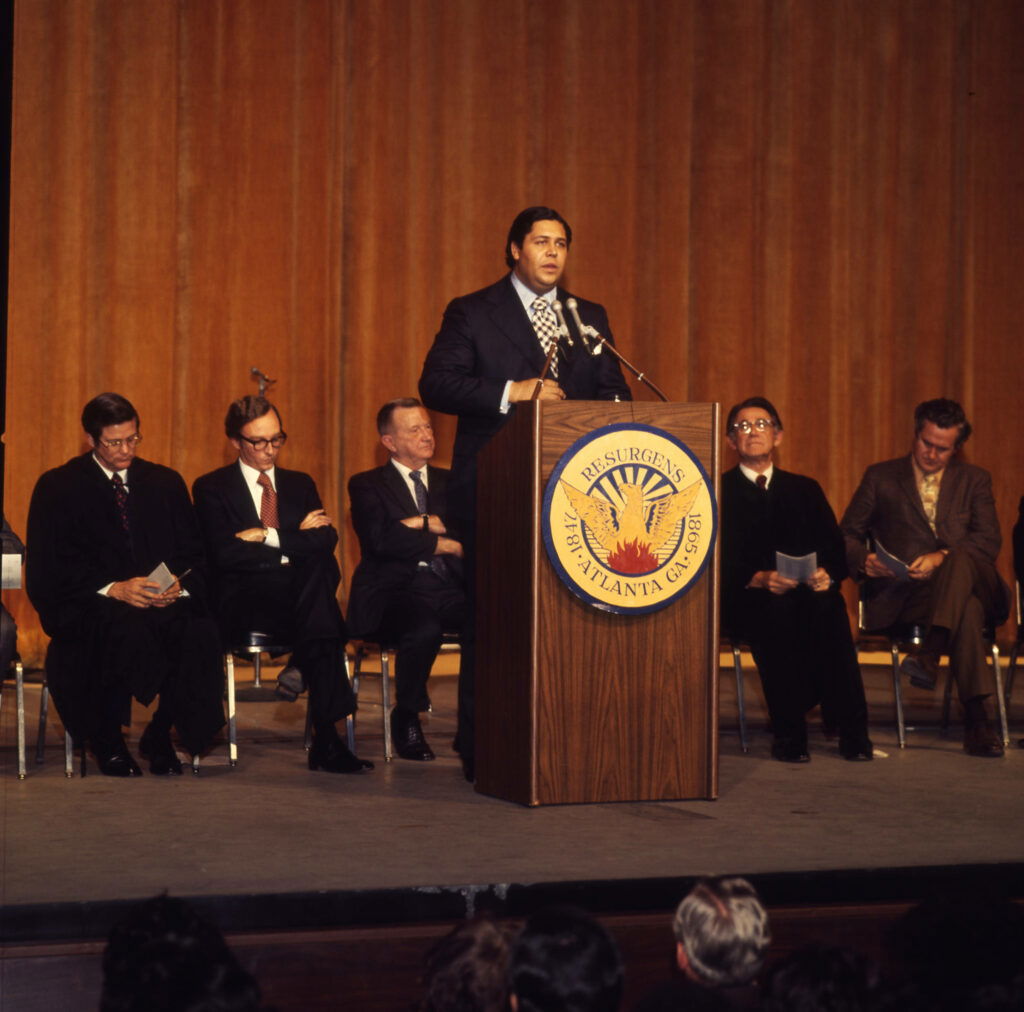

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Facing a legal limit of two consecutive terms, Jackson helped convince congressman Andrew Young to run to succeed him. Young won easily. In 1977 Jackson married advertising executive Valerie Richardson, whom he had met in New York after a divorce with his first wife the previous year. Jackson and Richardson had two children, Valerie and Alexandra. In the meantime Jackson became a successful municipal-bond attorney as the Atlanta representative of a Chicago law firm. His political and business prominence led to service on numerous boards in the 1980s and 1990s, including those of Morehouse College, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the Georgia Department of Industry, Trade, and Tourism (later Georgia Department of Economic Development).

Behind the scenes Jackson remained influential in city politics during Young’s administration, and he decided to seek a third term in 1989. Civil rights activist Hosea Williams ran against him, but Jackson carried nearly 80 percent of the vote. Jackson held greater support across racial and economic lines during his third term because he had mended ties with much of the white business community in the 1980s while Young was mayor. In one of the defining events of his third term, Jackson defused a two-week standoff by promising 3,500 new housing units for the poor after homeless protesters seized an abandoned downtown hotel. Although Payne, Young, and others were more intimately involved in the bid to bring the 1996 Olympic Games to Atlanta, Jackson assisted the effort and represented the city at the 1992 games in Barcelona, Spain. Also during his third term, scandals regarding payoffs and cronyism in airport concessions involved Jackson’s associates, though he was never implicated. Jackson denied any wrongdoing and declared that he had “a record of fighting corruption at the airport.”

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

In the fall of 1992 Jackson underwent major heart surgery, and the following spring he declared that he would not seek a fourth term due to medical and personal concerns. It seems likely that he would have been reelected had he run. At first Jackson supported the candidacy of city councilman Bill Campbell, though he later distanced himself from Campbell as scandals arose. Shirley Franklin, a longtime Jackson staffer, succeeded Campbell as mayor in 2002 with strong support from Jackson.

In 1994 Jackson returned to the bond and security business, this time founding his own firm. The Atlanta Business Chronicle reported that the state employee and teacher retirement systems were Jackson Securities’ largest clients. Among his many civic projects, he founded and funded a foundation to empower Black youth with leadership skills. Jackson held several major roles for the Democratic National Committee and in 2001 was in the running to become party chairman. He was also widely considered to be a possible candidate to succeed Zell Miller in the U.S. Senate after Miller announced his plans to retire, but Jackson took himself out of the race early in 2003.

Jackson died of a heart attack in Washington, D.C. on June 23, 2003. His body was placed in a coffin for viewing at Atlanta’s city hall and at Morehouse College, and the memorial service at the Atlanta Civic Center drew more than 5,000 mourners.

In 2008 Southside Comprehensive High School in Atlanta was renamed Maynard Holbrook Jackson High School in his honor, and in 2012 the Maynard H. Jackson International Terminal opened at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. Jackson’s mayoral records are housed at the Atlanta University Center’s Robert W. Woodruff Library.