A massive five-sided edifice, Fort Pulaski was constructed in the 1830s and 1840s on Cockspur Island at the mouth of the Savannah River. Built to protect the city of Savannah from naval attack, the fort came under siege by Union forces in early 1862 and was ultimately captured on April 11.

Origins and Construction

Following the War of 1812, the U.S. government began planning a system of coastal fortifications to defend the nation’s coast against foreign invasion. Because Savannah was the major port in Georgia, navy officials recognized the need for a fort on Cockspur Island to protect the city from attacks coming up the Savannah River. In 1829 construction began on the new fort, named for Count Casimir Pulaski, a Polish immigrant who fought during the American Revolution (1775-83).

Photograph by Brooke Novak

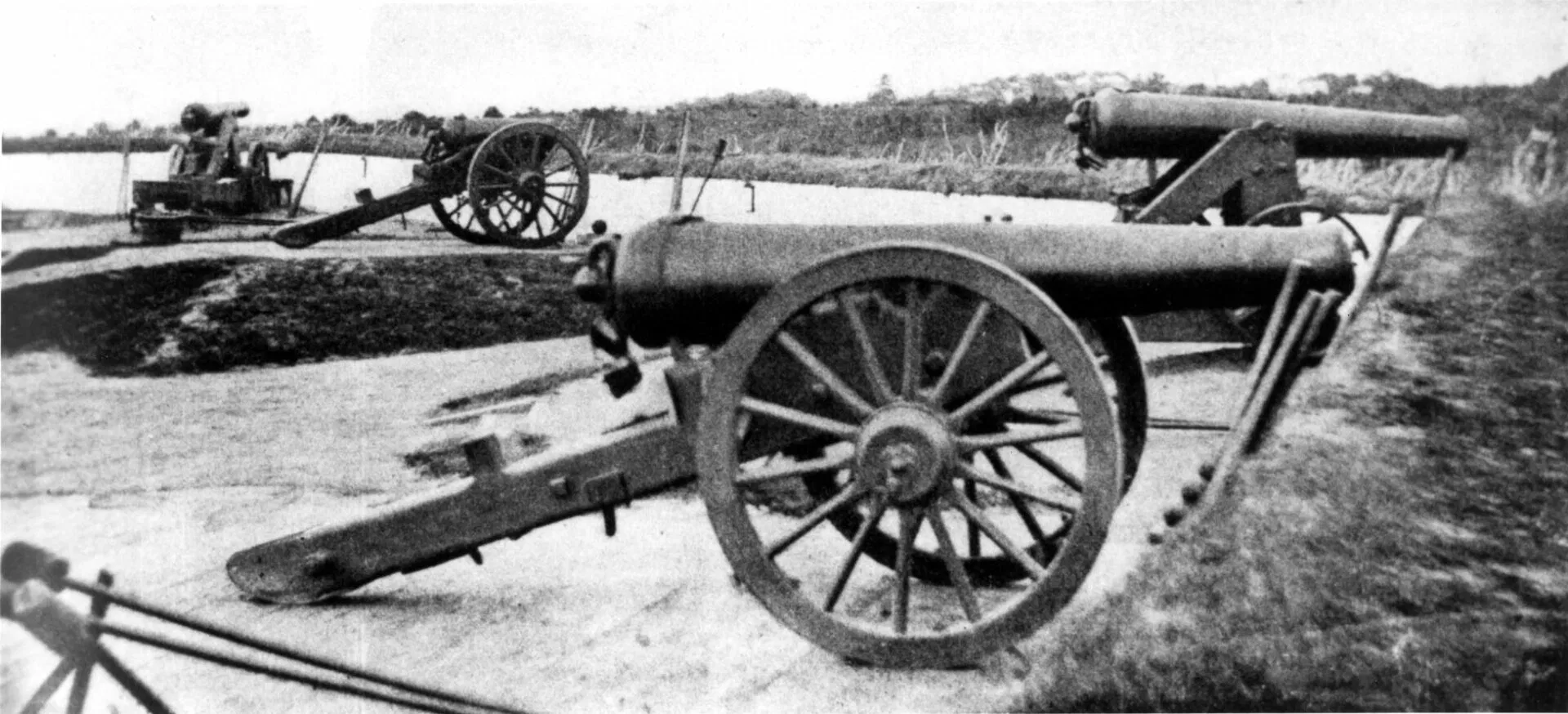

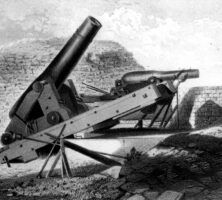

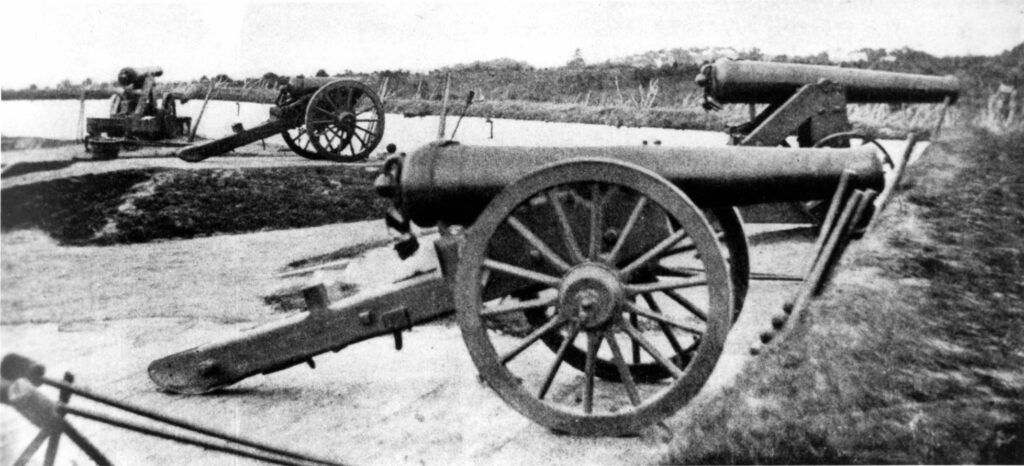

Responsibility for most of the early work on Fort Pulaski fell on the shoulders of Lieutenant Robert E. Lee, recently graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York. Lee oversaw the preliminary construction, choosing the site and designing a system of drains and dikes to support the weight of the masonry fort. In 1831 Lieutenant Joseph K. Mansfield took charge of Pulaski’s construction and oversaw the project for the next fourteen years. When finished in 1847, the fort could mount 146 cannons, some on the parapet atop the 7.5-foot-wide walls and others in casemates inside the walls.

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration.

Civil War

In January 1861, shortly before Georgia seceded from the Union, state troops occupied Pulaski to keep Union forces from garrisoning it. During the fourteen years since the fort’s completion, its condition had deteriorated considerably. Its moat had filled with mud, and not a single cannon was mounted in place. Five companies of troops from Macon and Savannah formed the garrison. Helped by enslaved people impressed from nearby rice plantations, these men cleared the moat and began to mount guns along the fort’s walls. By the time Colonel Charles H. Olmstead took command of Pulaski in December 1861, its defenses had improved dramatically.

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

Fort Pulaski faced its first threat during the Civil War (1861-65) in November 1861, following the capture of nearby Port Royal, South Carolina, by Union forces. General Robert E. Lee, commanding Confederate forces in the region, ordered Tybee Island and other islands near the fort abandoned because they could not be adequately defended. Lee believed, however, that Fort Pulaski’s wide walls would keep it from serious harm by any bombardment from Tybee, nearly a mile away.

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

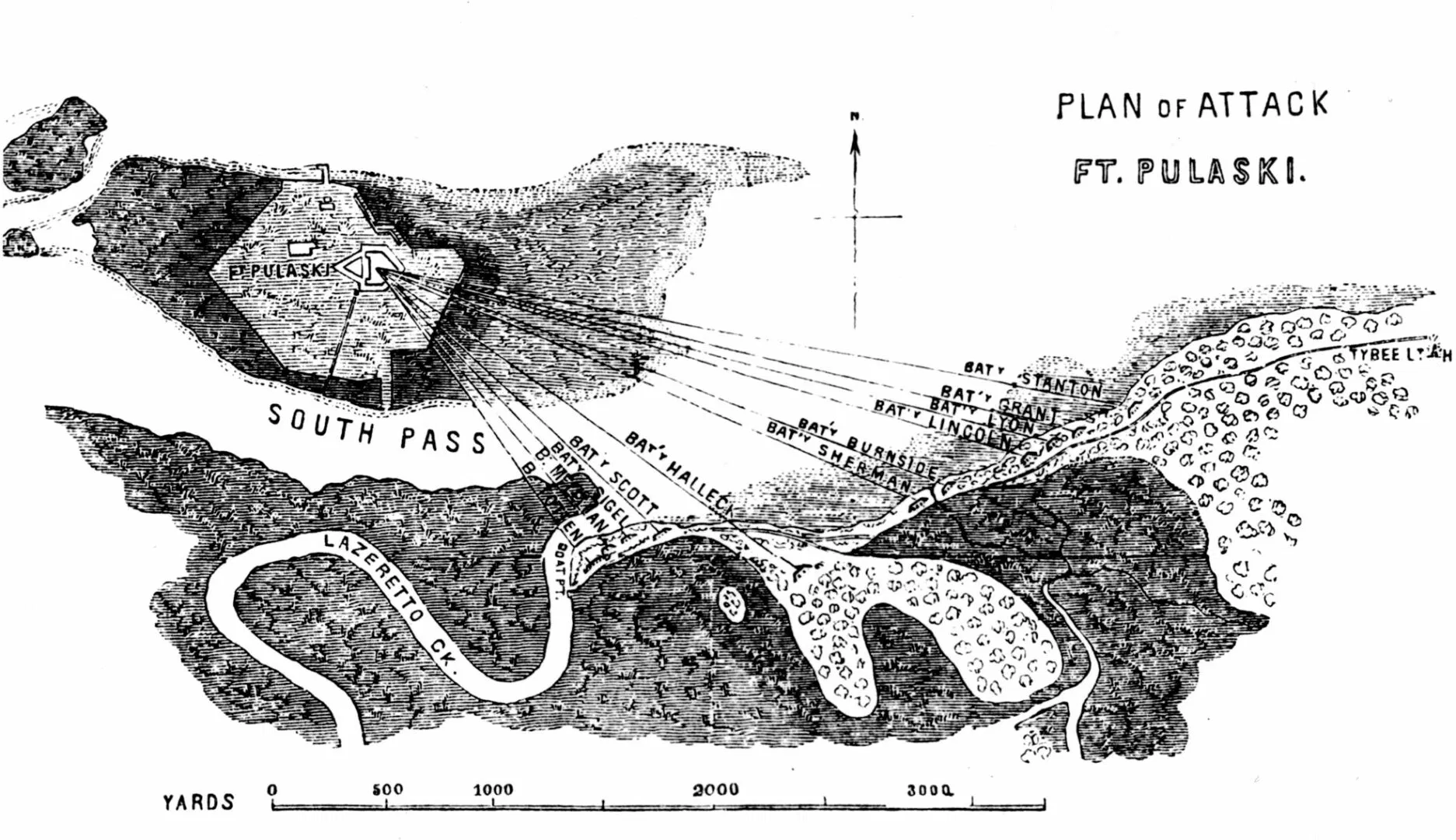

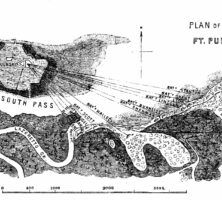

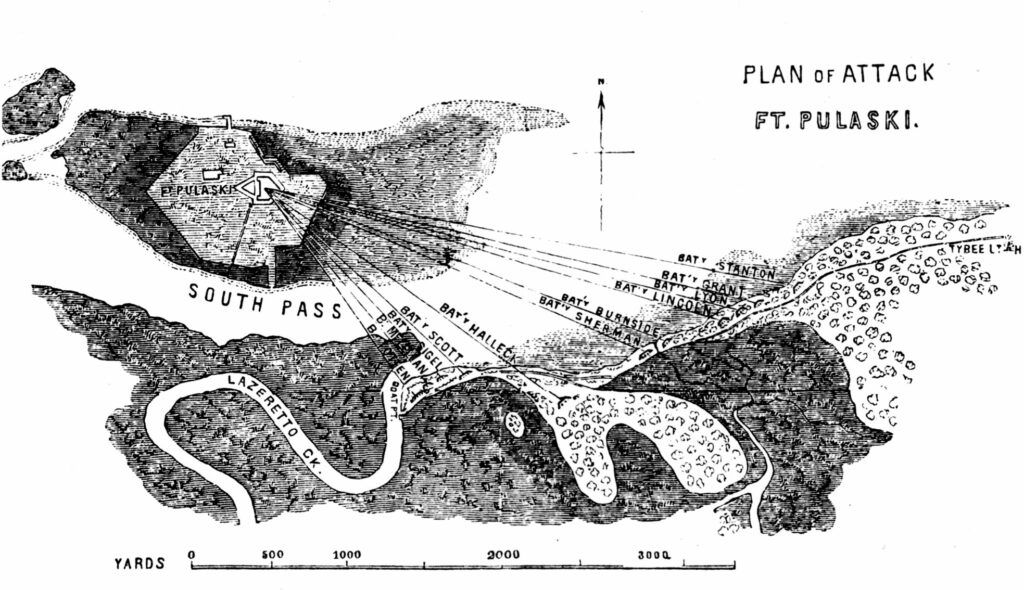

In February 1862 the Union commander in the district, Brigadier General Thomas W. Sherman, decided to take the fort by siege. He ordered troops to Tybee Island and constructed defenses on the smaller neighboring islands to cut the garrison from reinforcements. Sherman then placed Captain Quincy Gillmore of the Engineer Corps in charge of the siege preparations on Tybee, despite advice that “you might as well bombard the Rocky Mountains.”

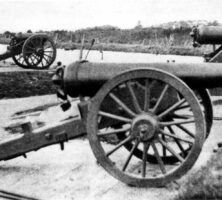

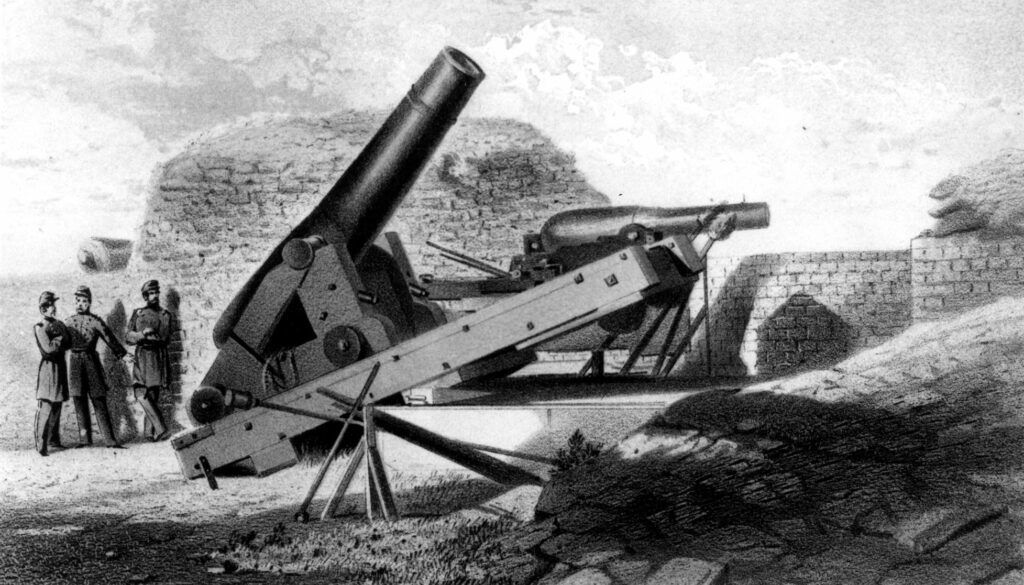

Gillmore ordered his engineers to construct a series of eleven artillery batteries along the north shore of Tybee Island. They worked mostly at night and camouflaged the work on the batteries to prevent the fort’s garrison from discovering their plans. Once the batteries were built, the troops had to pull, by hand, artillery pieces weighing as much as 17,000 pounds through marshy land and into position.

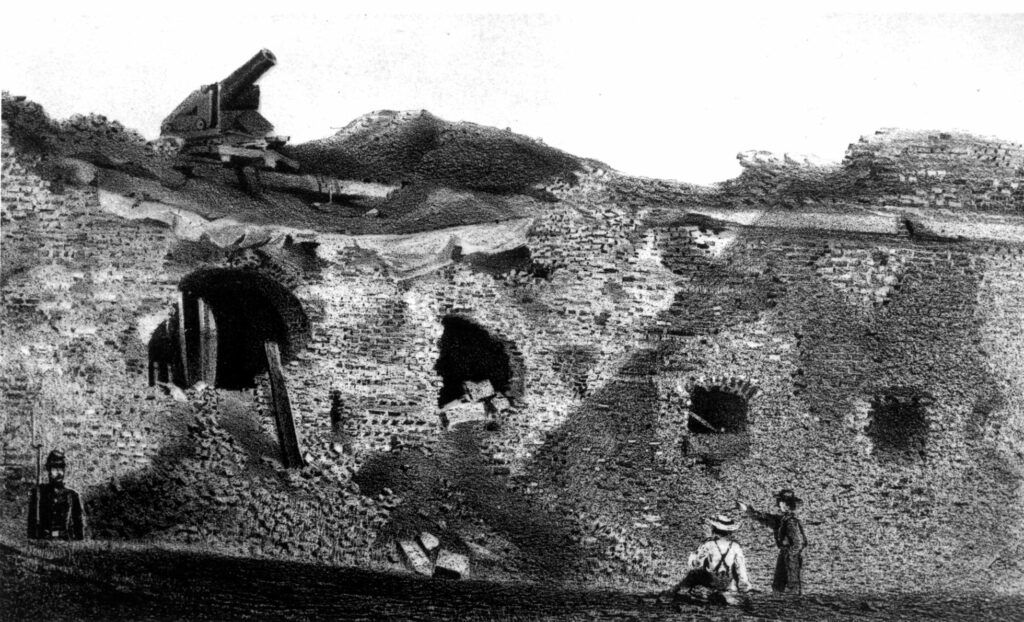

By April 9, Gillmore had twenty cannons and fourteen mortars in position to bombard Fort Pulaski. Just after sunrise the next morning he demanded the surrender of the fort. Colonel Olmstead declined, stating he was there “to defend the fort, not to surrender it.” The bombardment began at 8:15 a.m. with the Federal guns maintaining a slow, steady fire all day. By afternoon it became apparent that the heavy shells from the rifled cannons would be able to break through the walls of Pulaski. The guns from the fort returned fire but did no damage to the Union positions.

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

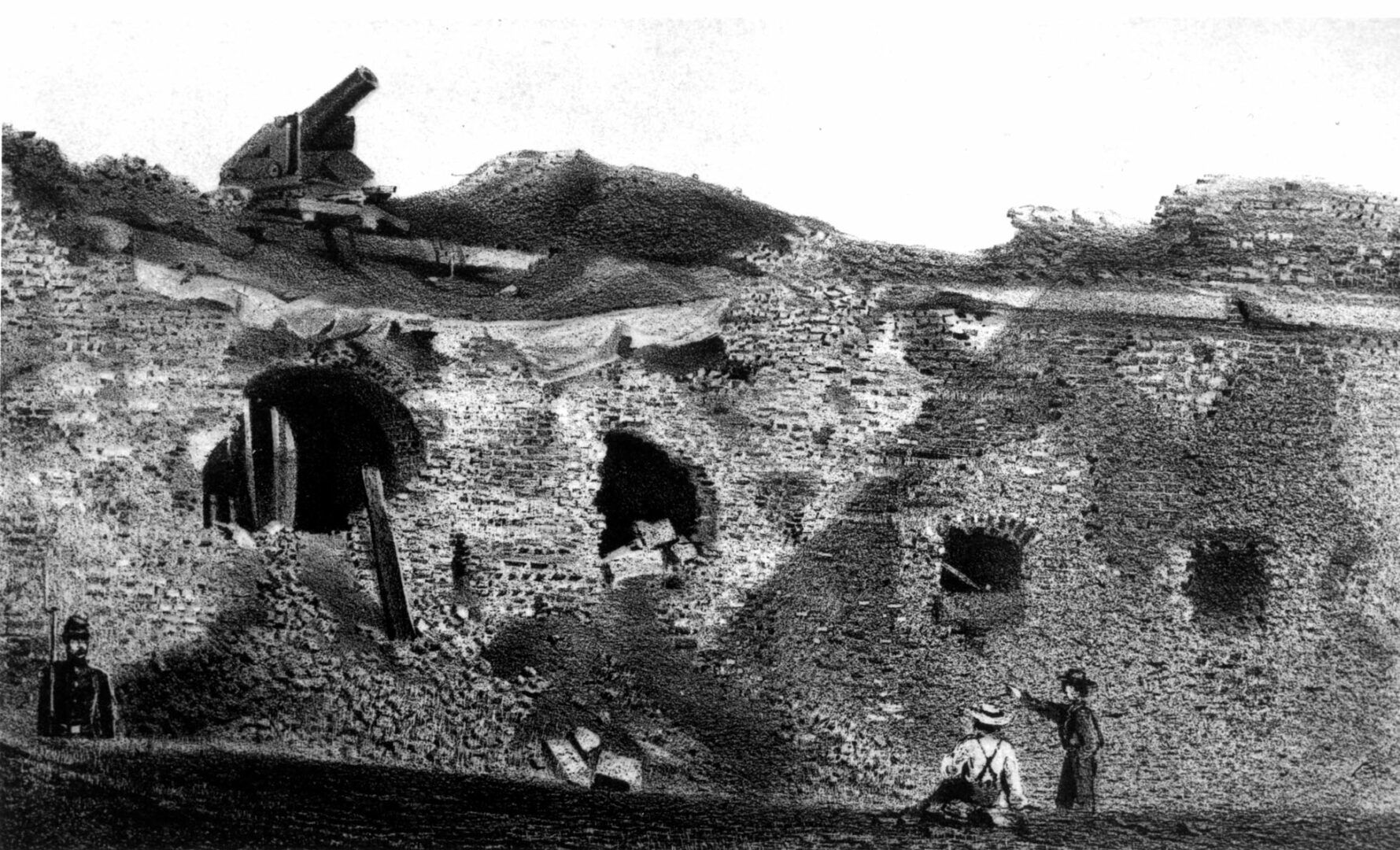

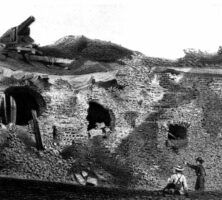

On April 11, the Union bombardment opened two thirty-foot holes in the southeast face of Pulaski. Soon, more shells were passing through the wall and striking the interior of the fort. Olmstead decided to surrender the garrison when the firing came perilously close to one of the main powder magazines. In less than thirty-six hours and with the loss of only one Union soldier, the new rifled cannons had brought the surrender of a fort that took eighteen years to build—a fort that some of the best engineers in both armies had said could not be reduced by such an artillery assault.

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

The reduction and capture of Fort Pulaski in 1862 not only deprived the Confederacy of a port it desperately needed but also signaled a major shift in the way future forts would be built as well as the way they would be attacked. Captain Gillmore took a risk when he decided to assault the fort with the new rifled cannons, but his gamble paid off and led to significant changes in military engineering.

Postwar

Image from Ron Cogswell

Following the surrender, Union troops garrisoned Fort Pulaski until the end of the war. During this period the fort served not only to bar Confederate shipping from Savannah but also to imprison captured Southern troops. After the Civil War (1861-65), the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began modernizing the fort but stopped before the project was completed. Pulaski remained virtually abandoned until 1924, when the government designated it a national monument. Nine years later it became a unit of the National Park Service, which continues to maintain it.