Olympics Out of Cobb (OOOC) was a grassroots movement resisting the decision by the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games (ACOG) to hold the preliminary volleyball competition of the 1996 Olympic Games in Cobb County. The county came under scrutiny from local and national LGBTQ+ rights groups in 1993 when the Board of Commissioners passed a resolution condemning “gay lifestyles.” Cobb’s commissioners refused to rescind the resolution and the events were ultimately moved to Athens.

The Games Come to Atlanta

After five rounds of voting, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) announced that Atlanta would host the 1996 Summer Olympic Games. The Centennial Games would be the first games hosted in the U.S. South.

Tasked with finding venues for the Games, ACOG identified dozens of sites throughout the state and region. But most events took place across multiple counties within metro Atlanta. Though their primary aim was to find sites that would best serve Atlanta’s international guests—the Olympic athletes—ACOG would encounter and navigate social, cultural, and political divides within greater Atlanta’s diverse population. ACOG faced pressure from numerous local organizations including the anti-poverty group Open Door Community, Concerned Black Clergy, Emmaus House, and the newly formed Atlanta Neighborhoods United for Fairness (ANUFF), each of which opposed the displacement of vulnerable populations and the redevelopment of in-town neighborhoods.

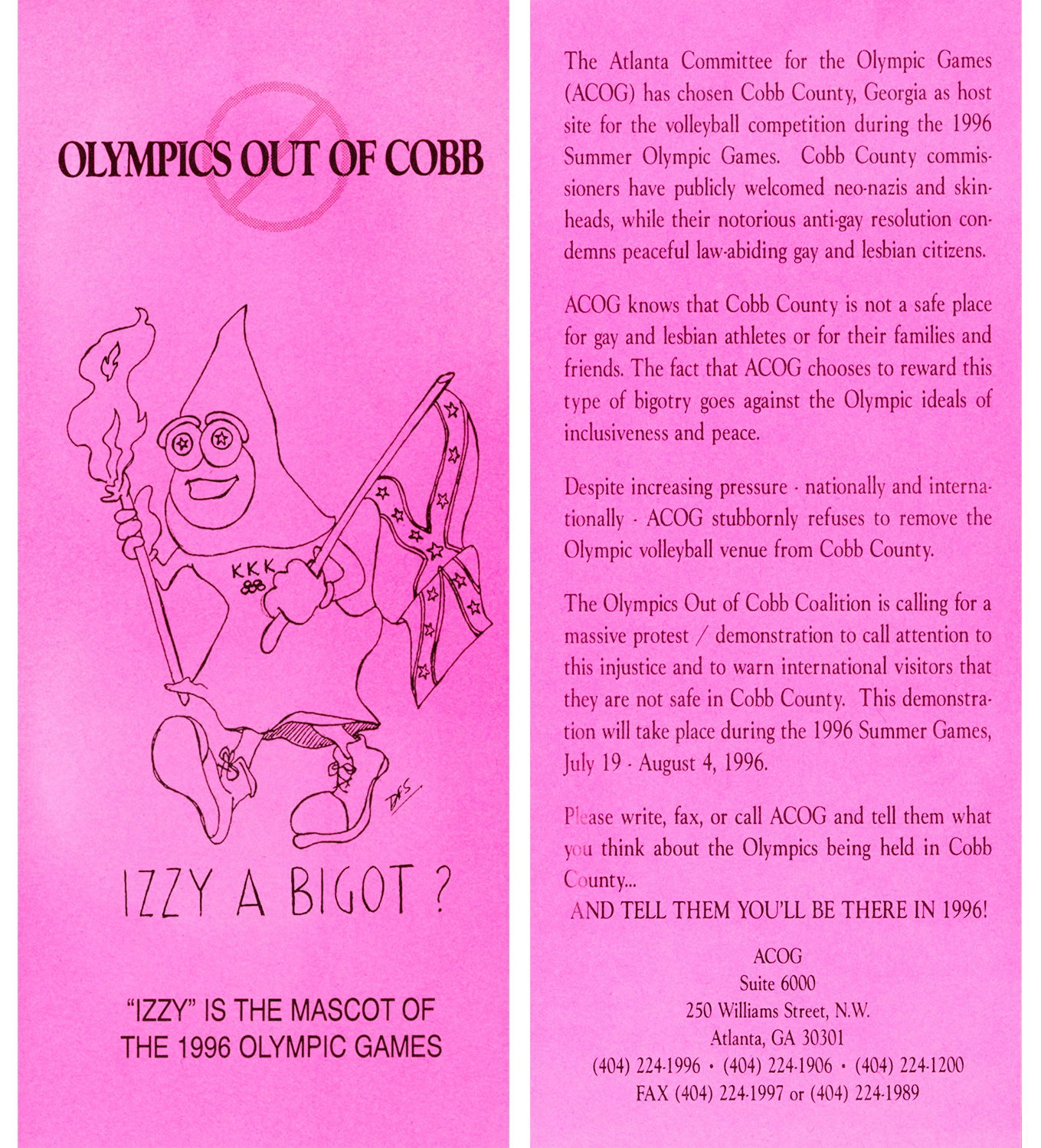

One of the more visible challenges to ACOG’s work came from a group that did not exist until 1994 and would be dissolved within the year. They would quickly become known by their primary objective: Olympics Out of Cobb.

Background: Cobb County

In 1986, the same year that the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Georgia’s sodomy law in Bowers v. Hardwick, the Atlanta City Council voted to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. By August 1993 the city council had adopted ordinances that both recognized and extended benefits to same-sex domestic partnerships.

Under the stewardship of Commissioner Gordon Wysong, nearby Cobb County went in a different direction. Following a controversy over the 1993 staging of Terrence McNally’s Lips Together, Teeth Apart at Marietta’s Theatre in the Square (founded in 1982 by gay couple Michael Horne and Palmer Wells), Cobb County Board of Commissioners passed an anti-gay resolution condemning what it called “gay lifestyles.” Commissioners also stated that they would not fund activities that violated “community standards.” Further, the Commissioners passed a separate resolution revoking Theatre in the Square’s $40,000 annual grant. Following the unanimous vote, the Atlanta Constitution noted that the resolution “amounts to official government condemnation of a whole group of people.”

Local leaders and allies quickly organized against the resolution. Marietta activist Jon Greaves helped organize the Cobb Citizens Coalition (CCC), which led demonstrations and protests, called for boycotts, and erected a billboard on Interstate 75 that read, “Stop the Hate! Rescind the Resolution.”

OOOC’s Two Unlikely Co-Chairs

On January 30, 1994, ACOG announced its intention to host preliminary volleyball competitions at the Cobb Galleria Centre just off I-75. Following CCC activism against the anti-gay resolution, local LGBTQ+ communities were outraged that the IOC, which claimed to support human rights, would tacitly endorse what they viewed as a flagrant attack on their rights.

Though he had limited experience as an organizer, Atlanta resident Jon-Ivan Weaver quickly emerged as a vocal critic of ACOG’s decision. With few connections to the activist community, Weaver’s initial calls went unreturned. But by February 1994, a small group of supporters had coalesced around Weaver, and with guidance from more seasoned activists such as Jeff Graham and Mona Bennett (Love) of Atlanta’s AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) and Lisa Kung of the Lesbian Avengers, he emerged as the new group’s de-facto leader.

A chance encounter at Charis Books and More, however, gave the group its biggest boost. Weaver met Pat Hussain, a veteran activist who had worked with the NAACP, GLAAD, Southerners on New Ground (SONG) and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (NGLTF). Hussain’s connections and activist skillset supplemented Weaver’s inexperienced passion. The group formally named itself Olympics Out of Cobb (OOOC) and elected Weaver and Hussain as co-chairs. Through her contacts, Hussain learned that ACOG had not yet signed the contract securing the Cobb Galleria Centre.

Demands & Direct Action

In the months that followed, OOOC worked various channels to achieve their two primary objectives, the removal of the volleyball competition from Cobb County and full repeal of the Cobb County’s “homophobic resolution.” They insisted that Cobb County “receive no direct economic benefit from the 1996 Olympic Games,” and called on Shirley Franklin, future Atlanta mayor and Senior Vice President for External Relations with ACOG, to create an advisory panel on human rights that would include members of the LGBTQ+ community.

What’s more, members borrowed tactics from groups like ACT UP and pledged to protest all the way to the Games if necessary. OOOC showed up at ACOG events and press conferences; they held protests and candlelight vigils for justice in Woodruff Park; they picketed the Marriott Marquis when IOC president Juan Antonio Samaranch came to Atlanta; they instigated a slowdown of Interstate 75; they flew banners over the April Dogwood Arts Festival. They came out in force at the 1994 Atlanta Pride parade and festival, where Weaver and Hussain were honored as Pride Grand Marshalls. Protesters called out the president of ACOG in particular, chanting, “Billy Payne do your job! Get the Olympics Out of Cobb!”

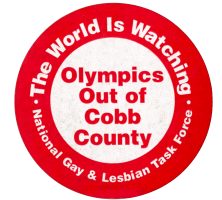

Despite pushback, OOOC grew as local and national support intensified over the summer of 1994. OOOC representatives attended the Stonewall 25 Celebration in New York City in late June, where they spoke at a NGLTF event, carrying stickers that read, “The World is Watching: Olympics Out of Cobb County.” The organization waged an effective media campaign as well, publicizing support from prominent political leaders and cultural figures. Early on, Congressman John Lewis wrote a letter of support “urging the Olympic Committee not to be identified or associated with places and symbols of bigotry and intolerance.” Shannon Byrne, daughter of Cobb commissioner Bill Byrne, announced she was a lesbian that June and denounced the anti-gay resolution. And openly gay Olympian Greg Louganis called for the volleyball events to be removed from Cobb County at a press conference in St. Louis that July. “It’s not an issue of politics but fairness,” he stated.

Negotiation & Resolution

Though the more visible parts of OOOC work included public actions and media presence, OOOC leaders also worked to achieve their demands through private negotiations with ACOG leadership. Between March and July, Hussain and Weaver held seven meetings with two ACOG representatives, Shirley Franklin and attorney David Getachew-Smith. In each meeting, Hussain reiterated simply but forcefully, “You need to move the venue.” In their final meeting on July 20, it became clear that ACOG would have to capitulate. Nine days later, ACOG announced that they were moving the volleyball events from Cobb County to a venue in Athens. The announcement made headlines nationwide, but New York’s Village Voice put it best: “Imagine a ragtag bunch of queers standing up to the biggest of big-money politico-athletic cartels in the world—and winning.”

Though Franklin represented the opposing side in the debate, the future mayor encouraged Hussain and Weaver to document their victory: “You know, what you have accomplished is a very important thing. This will be remembered and have a place in the history of the Olympics… I don’t think the record of what happened should be lost.”