The Vietnam War (1964-73) transformed the United States. The effects of the conflict were far-reaching, not only for the nation’s geopolitical and military policies, but also for its social fabric. In Georgia, as in most of the states in the Deep South, the majority of the population supported the war effort. As the war dragged on, however, Georgians, like many Americans, began to question the decision to go to war, to criticize its prosecution, and to long for an end to hostilities.

The Decision for War

From 1946 to 1954, Vietnamese communists led by the charismatic Ho Chi Minh waged a war of independence in French Indochina. The United States became increasingly drawn into the conflict as Presidents Truman and Eisenhower provided financial and military aid to the French in their struggle against the Viet Minh guerrillas. Following the French defeat in 1954, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam gained independence. Vietnam was temporarily partitioned between North and South until a unification election could be held in 1956. Those elections never happened, and the U.S. set about building an anti-communist bastion in South Vietnam.

During the next eight years, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and South Vietnamese communist guerrillas (the National Liberation Front or Vietcong) waged an ever-widening war to reclaim South Vietnam. The U.S. responded with millions of dollars in military and economic aid and an increased number of military advisors, yet the situation continued to deteriorate. Following the assassination of President Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in as the thirty-sixth president of the United States, and he inherited a volatile situation in Vietnam.

Increasingly flagrant Vietcong attacks on bases housing U.S. advisors and an infamous strike on an American warship in the Gulf of Tonkin in 1964 led Johnson to petition Congress for extraordinary war powers in the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. Johnson was relying on southern Democrats for support in gaining congressional authorization to use military force in Southeast Asia without seeking an official declaration of war.

Two Georgians played prominent roles in Johnson’s strategy—Dean Rusk, who served as Johnson’s Secretary of State, and Senator Richard B. Russell Jr., who headed the Senate Armed Services Committee. Russell supported communist containment but opposed a U.S. land war in Southeast Asia, which he felt was not in the vital interests of the country. However, he bowed to Johnson’s pressure and, using his considerable clout, joined his fellow southern congressional Democrats to support the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. Dean Rusk had no such qualms. An unabashed hawk, Rusk worked with Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and other cabinet members to convince the president that U.S. military superiority would triumph in Vietnam, thereby saving that nation and surrounding nations from falling to the spread of communism.

Most Georgians, like Russell, were initially reluctant to go to war, but their fear of world communism, coupled with fervent patriotism, convinced them to support the president. Ideology and fear were not the only deciding factors. The Cold War had benefited Georgia and the rest of the South. During the 1960s, Georgia ranked among the top ten states for defense contracts. Indeed, by the middle of the decade, the federal government had invested $762 million in fifteen major military installations and was paying more than $640 million a year to civilian employees. Moreover, defense-related businesses became the state’s largest employers. The Lockheed-Georgia corporation, one of the South’s largest employers, operated in one-third of Georgia’s counties. Part of the reason the South benefitted from defense spending was that Senator Richard Russell and Congressman Carl Vinson, both from Georgia, controlled the all-important Senate and House Armed Services Committees.

Looking for Victory, 1965-1968

While Johnson, Rusk, and Russell hoped that airstrikes alone might force North Vietnam into ending its aggression against South Vietnam, the deteriorating military situation required extensive U.S. ground forces to help the nation to survive. Reluctantly, Johnson decided to send ever-increasing numbers of combat troops to South Vietnam. By 1968 the U.S. commander in South Vietnam, General William Westmoreland, commanded more than half a million troops. His strategy of attrition warfare was designed to wear down the enemy with superior force. Johnson supported the attrition strategy because he wanted a limited war and worried that an overly aggressive stance would lead to direct Russian or Chinese involvement. But rather than bring North Vietnam to the negotiating table, intermittent bombing only produced a military stalemate.

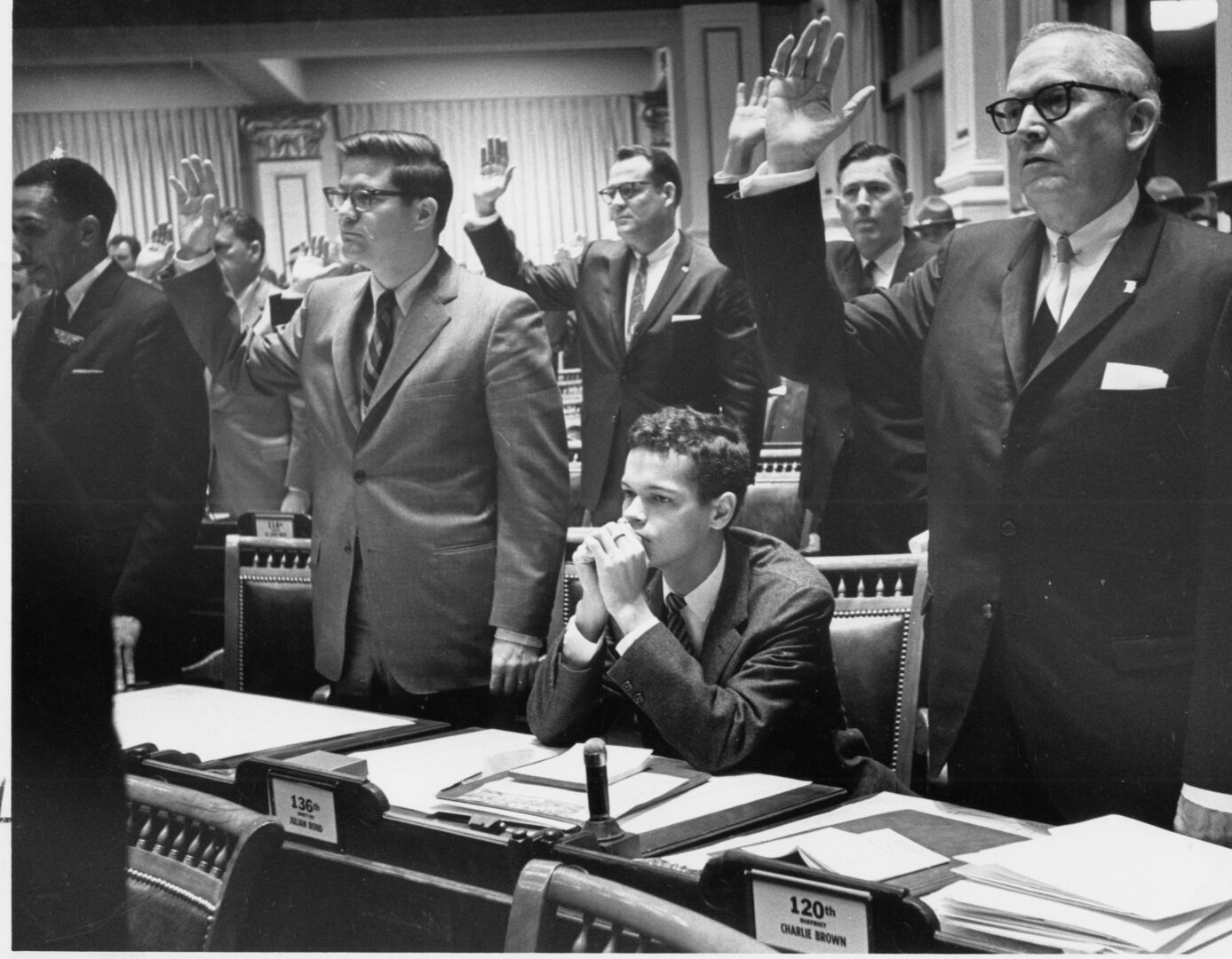

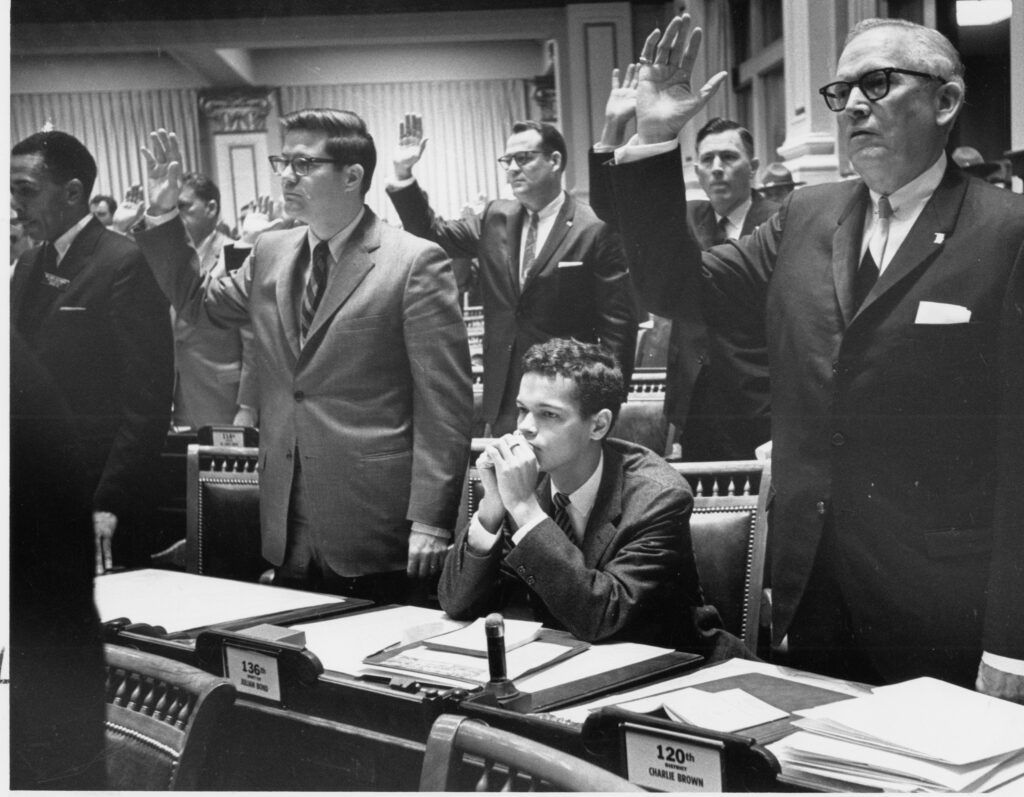

While most southerners supported Johnson, and major newspapers such as the Atlanta Constitution endorsed the United States’ role in the conflict, a vocal majority called for even more aggressive bombing and an abandonment of the failing attrition strategy. Admittedly, a few influential southern politicians such as Senators Albert Gore Sr. and J. William Fulbright advocated an end to U.S. involvement. Moreover, Black southerners, while patriotic, struggled with the certainty that they were more likely to be drafted and serve in combat because of racial bias in the deferment and classification system used by the military. African American leaders such as Julian Bond and Martin Luther King Jr. were more concerned with promoting domestic programs aimed at civil rights and poverty than containing communism in Southeast Asia. Indeed, even as Johnson worked toward a more equitable society through economic and civil rights legislation, he drew the ire of white southern politicians whom he desperately needed to support the war in Vietnam.

The tenuous situation deteriorated with the Tet Offensive of 1968. During the truce marking the lunar new year, communist forces hit targets across all of South Vietnam. U.S. forces successfully repelled each of the attacks, but the coordinated strikes became a public relations nightmare in the U.S. After years of being promised that victory was inevitable, the countrywide offensive shocked the American public and persuaded many that the war, in actuality, could not be won.

Looking for a Way Out, 1969-1972

Tet destroyed Johnson’s credibility and drove his decision not to seek reelection. Many in Congress pushed the president and Rusk to negotiate a compromise peace settlement. Georgia and other southern states remained bastions of pro-war support, however. While Herman Talmadge encouraged his fellow congressmen to stand firm against communist aggression, newspaper publisher Ralph McGill and editor Eugene Patterson of the Atlanta Constitution continued to advocate a vigorous war against North Vietnam. In addition, Russell supported the provision of additional troops, a blockade of North Vietnam, and heavier bombing of that country’s limited infrastructure.

The election of Richard Nixon convinced southern hawks that “peace with honor” could be achieved. Nixon’s tough stance on communism and his lukewarm support of civil rights garnered him the support of many southern whites, despite the region’s long affinity for the Democratic Party. The president’s escalation of the conflict through intensified bombing of North Vietnam and incursions into Cambodia enjoyed greater support in the South than other areas of the nation. But despite his bellicose rhetoric and actions, Nixon was lowering U.S. troop levels and working behind the scenes to negotiate a peace deal.

Like their fellow southerners, Georgians remained fiercely committed to the war effort, even as others lost confidence in its progress and purpose. The case of Lieutenant William Calley Jr., who was implicated in the My Lai Massacre, illustrates the extent of the region’s conservatism and support for the military. Across the South, politicians spoke out in Calley’s defense. In Georgia, Senator Herman Talmadge and Representative Ben B. Blackburn maintained that Calley was a scapegoat. Additionally, Lieutenant Governor Lester Maddox, along with Alabama governor George Wallace, spoke at a pro-Calley rally in Columbus near Fort Benning, where Calley was being held, while members of Georgia draft boards threatened to resign if Calley was not exonerated.

Despite their militarism, many Georgians eventually succumbed to war-weariness. Even the Atlanta Constitution turned anti-war by 1970 and applauded Herman Talmadge’s unexpected change of position and call to end the conflict. Talmadge spoke for many who simply wanted the war brought to an end, an outcome finally achieved by the Nixon administration in 1973. Although the peace treaty left thousands of communist forces in South Vietnam and virtually assured the fall of the country, it was enough to finally extricate American troops from the conflict.

Georgians in Vietnam

More than 200,000 Georgians served in the Vietnam War. The experiences of these soldiers, sailors, and airmen were not markedly different from those of their fellow southerners or, indeed, most Vietnam veterans. Many of the state’s servicemen later recalled the difficulty of fighting a guerrilla war against an elusive enemy. Most of those in the ground war recalled long periods of boredom on patrol punctuated by intense combat through ambushes. They ate little, slept little, and had great difficulty moving through the jungles, swamps, and mountains of South Vietnam. And in addition to physical injuries sustained on the field of battle, many veterans would later suffer mental anguish and distress as a result of their service.

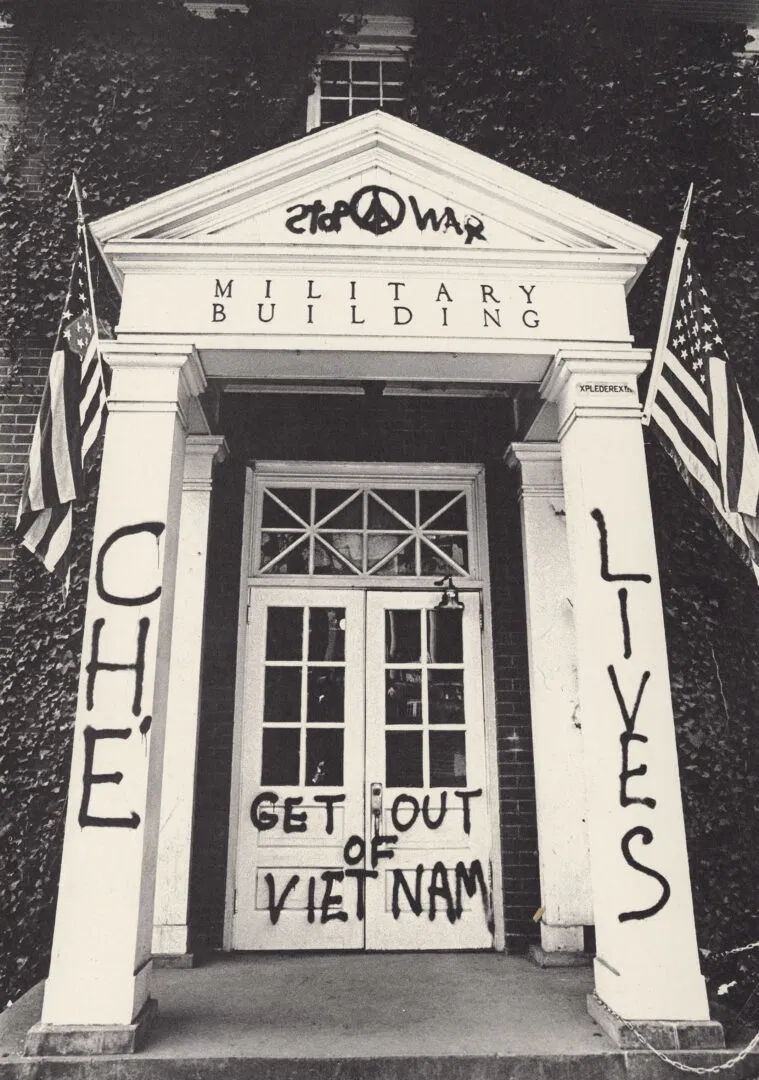

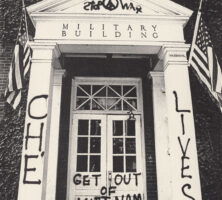

The Protest Movement

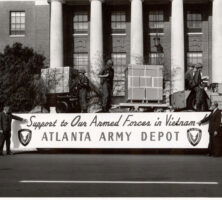

The position taken on the war by Georgia’s college students was largely determined by race. White college students, like their peers elsewhere in the South, generally supported the war; however, African American students continued to be primarily concerned with civil rights issues and biased draft procedures. They believed that fighting for freedom and equality at home was more important than fighting in a distant war. A few anti-war demonstrations did occur on college campuses, the most notable being the South’s first teach-in at Emory University in Atlanta that attracted more than 1,000 students in 1965. This demonstration was dwarfed by the more than 10,000 students who attended Affirmation Vietnam, a Georgia pro-war rally at the Atlanta Stadium (later Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium) in 1966.

The End of the War and Its Legacy

The close of the Vietnam War in 1973 marked a milestone in American history. One of the most divisive events in the history of the republic had come to an end. When South Vietnam fell to communist forces two years later, hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese nationals sought refuge in the United States, and many of these would later establish roots in Georgia. By 1990, nearly 7,000 residents of Vietnamese ancestry called Georgia home.

Though nearly a quarter of a million Georgians served in Vietnam, only a few memorials have been built across the state, such as the Georgia War Veterans Memorial Complex in Atlanta. In 2015 Georgia joined the national effort to commemorate the war’s fiftieth anniversary by providing all Vietnam veterans with a certificate of honor in recognition of their service. As of 2017 fewer than 20,000 had been issued, but state officials pledge to continue their efforts until all eligible veterans are acknowledged.

Perhaps Georgia’s most notable legacy of the war stems from Richard Russell’s criteria for U.S. military intervention, which influenced the Nixon Doctrine as well as future political and military leaders. This doctrine asserts that the U.S. should not enter a war without a direct threat to national security; at least part of the nation being occupied must support the U.S. effort; and the nation being aided must bear part of the burden of its own defense.