In February 1864, during the Civil War (1861-65), a Confederate prison was established in Macon County, in southwest Georgia, to provide relief for the large number of Union prisoners concentrated in and around Richmond, Virginia. The new camp, officially named Camp Sumter, quickly became known as Andersonville, after the railroad station in neighboring Sumter County beside which the camp was located. By the summer of 1864, the camp held the largest prison population of its time, with numbers that would have made it the fifth-largest city in the Confederacy. By the time it closed in early May 1865, those numbers, along with the sanitation, health, and mortality problems stemming from its overcrowding, had earned Andersonville a reputation as the most notorious of Confederate atrocities inflicted on Union troops.

Prison Conditions

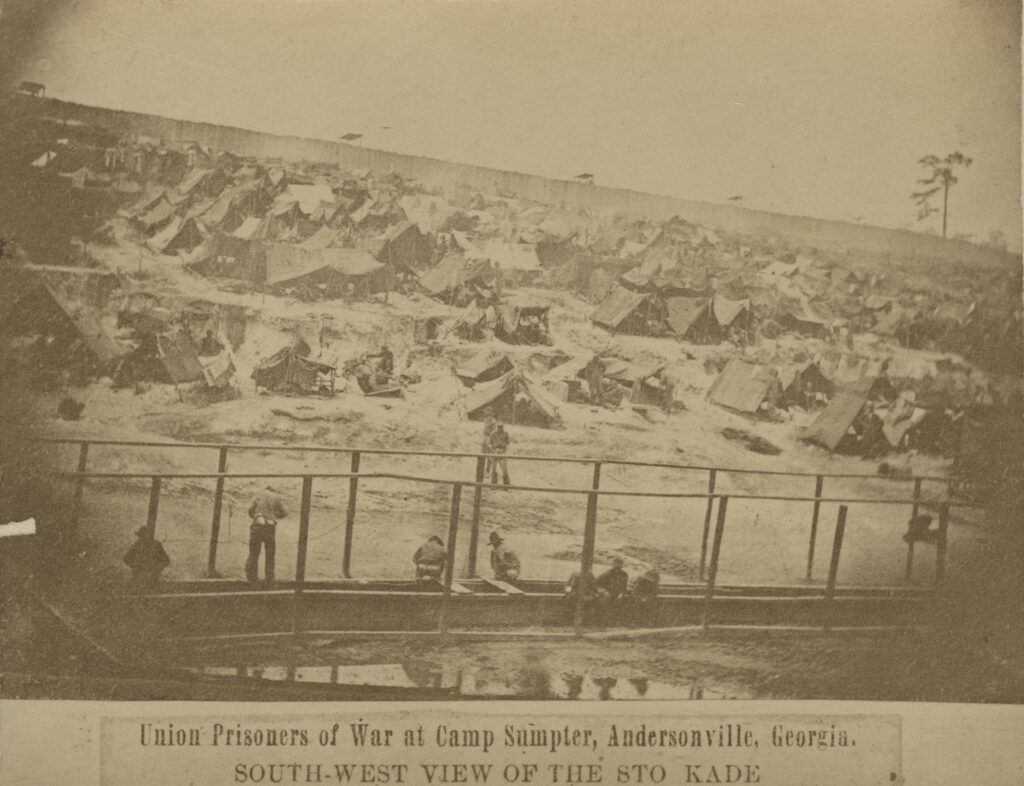

Andersonville station, the third of three sites considered by Confederate officials for the prison, lacked ready access to supplies. It was chosen, in fact, for its inland remoteness and safe distance from coastal raids and because there was little opposition from the inhabitants of this sparsely populated area. Local Black labor—slave and free—was impressed into service to build the camp, which consisted of a stockade and trench enclosing more than sixteen acres. A small creek, Stockade Branch, ran through the middle of the enclosed area.

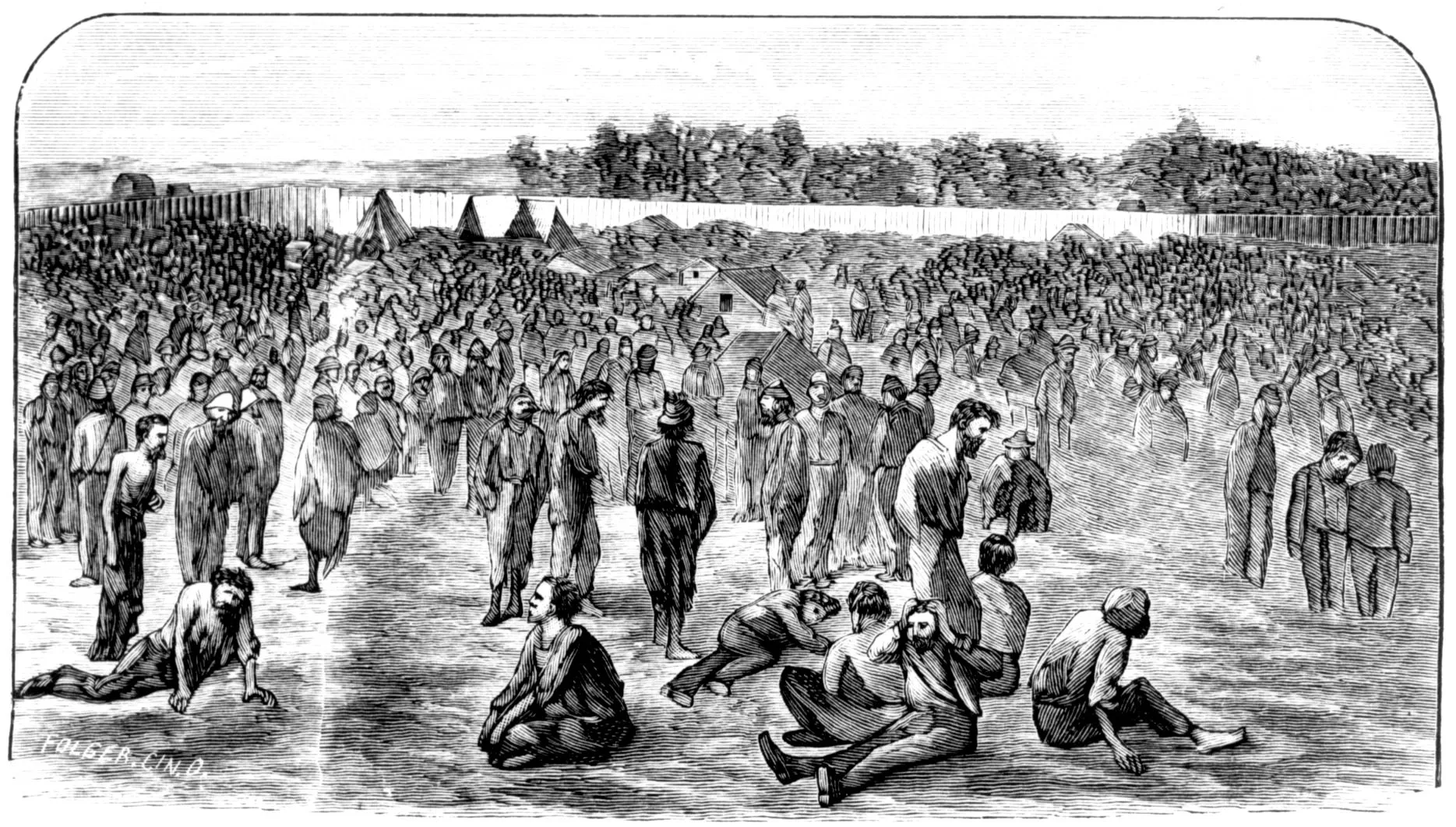

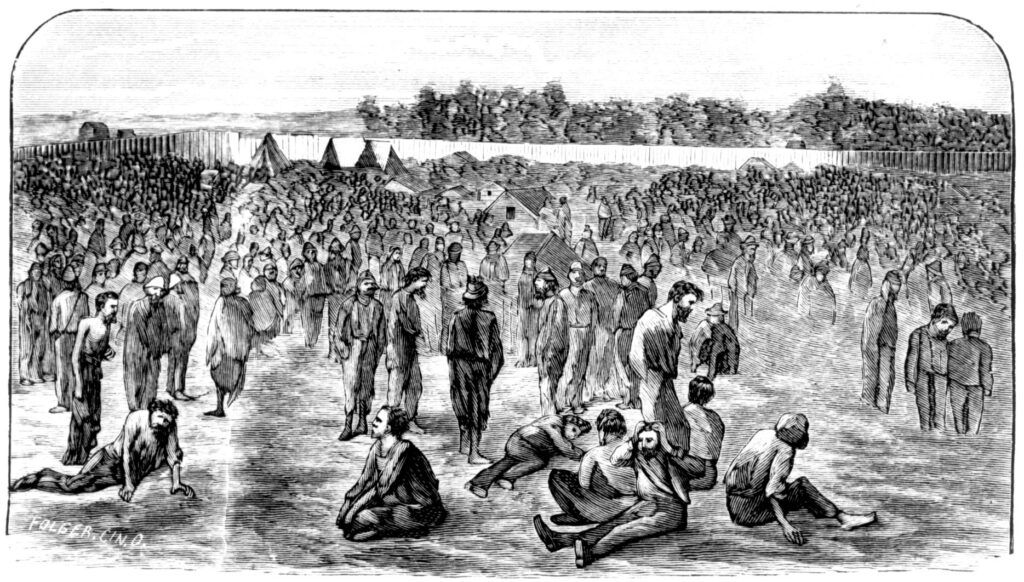

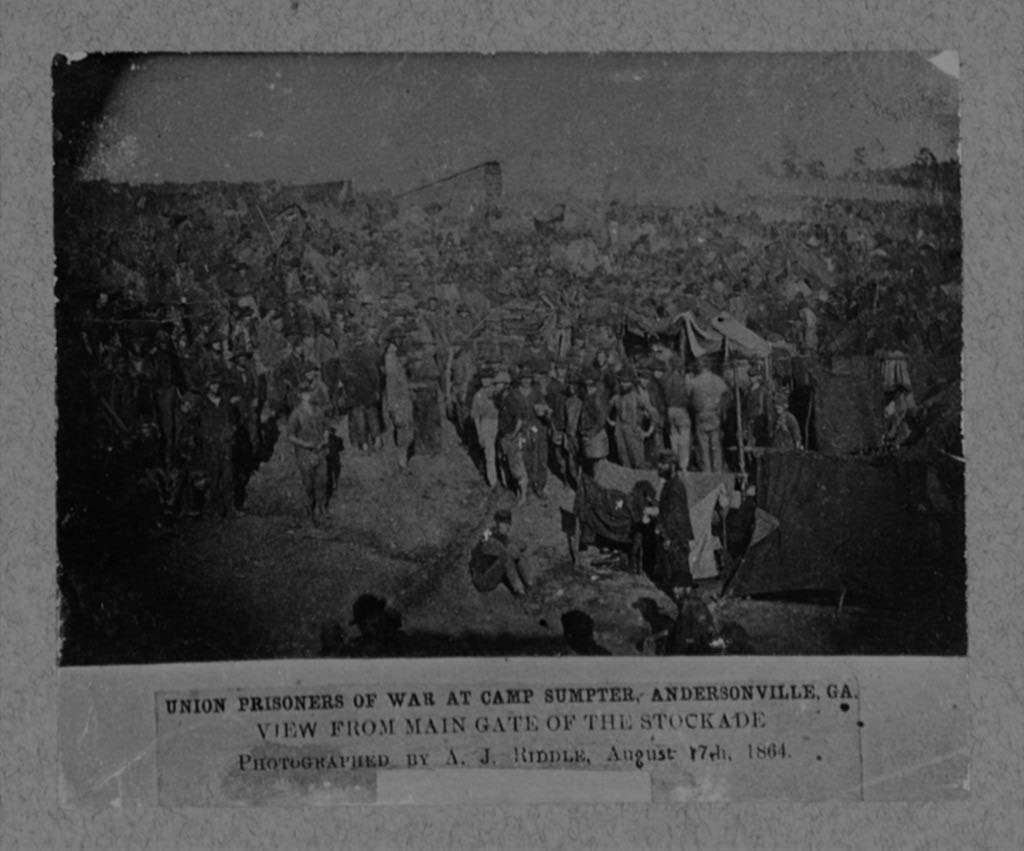

The camp was planned for a capacity of 10,000 prisoners, but with the breakdown in prisoner exchanges, which would have removed much of its prison population, its numbers swelled to more than 30,000. As the number of imprisoned men increased, it became increasingly hard for them to find space to lie down within the vast pen. The prisoners, nearly naked, suffered from swarms of insects, filth, and disease, much of which was generated by the contaminated water supply of the creek.

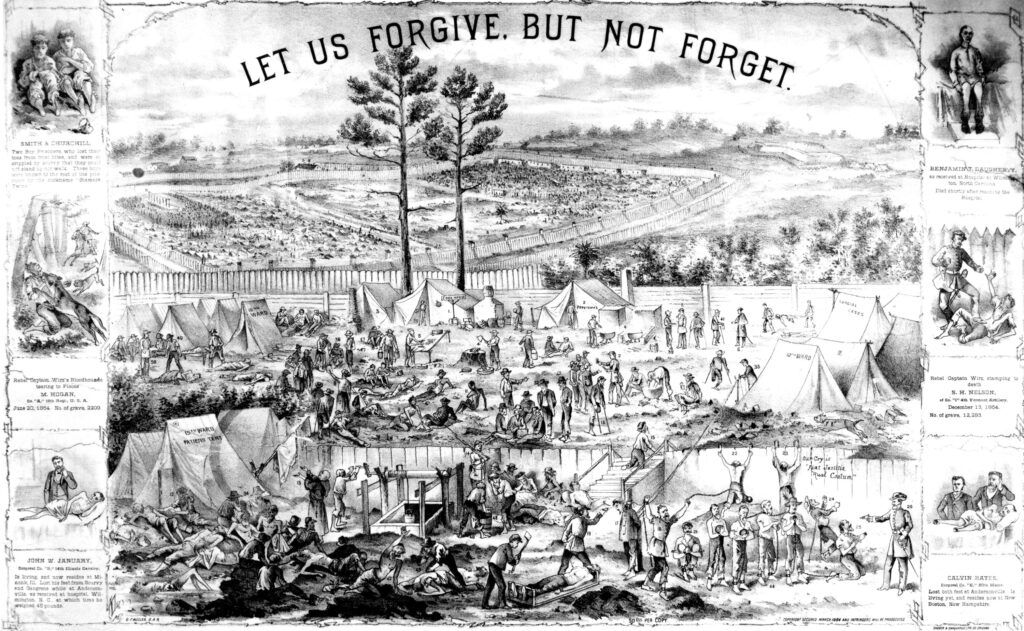

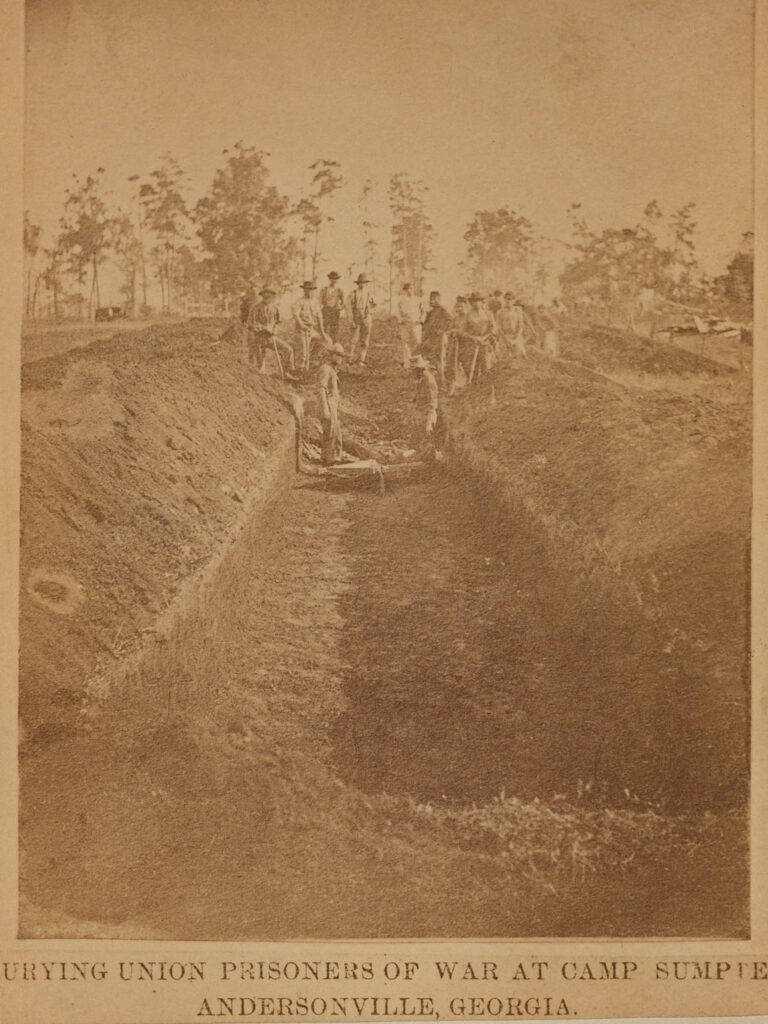

Andersonville had the highest mortality rate of any Civil War prison. Nearly 13,000 of the 45,000 men who entered the stockade died there, chiefly of malnutrition. Guards were also issued poor rations but had the option of foraging for food elsewhere. Critics charged that though the Confederate government could find the resources to move prisoners hundreds of miles and to build a facility in which to incarcerate them, it failed to provide adequate supplies or living conditions for the inmates or even for the staff.

In the summer of 1864 camp administrators, using the labor of Union prisoners and enslaved workers, expanded the prison’s size and facilities by constructing a hospital, a bakery, and some barracks. They also extended the stockade walls, adding an additional ten acres to the original site. Yet the overwhelming number of prisoners rendered their efforts hopelessly inadequate.

Prison Life

Prisoners did little to improve the miserable conditions under which they lived. Firewood details were curtailed when prisoners seized the opportunity to escape. The small stream that served as the camp’s primary water supply, both for drinking and bathing, was polluted by the unsanitary habits of some inmates and by sewage and other garbage dumped into the swampy area that fed the stream. Wells were covered over and made inaccessible after prisoners used them to hide escape tunnels.

Camp inmates often preyed upon each other. Gambling tents and “stores,” operated mainly by prisoners from Union general William T. Sherman’s western troops, fleeced new arrivals. Roving gangs of raiders, chiefly from eastern regiments, robbed fellow inmates, despite efforts by guards to stop them. The prisoners hanged six of the raider leaders on July 11, 1864. After that, a new police force made up of prisoners sought to impose discipline on their fellow inmates. They tried to enforce sanitation practices, curtail robberies, and force captive officers to take care of the men under them. Their strong-arm tactics led some inmates to see these new “regulators” as no better than the raiders. Men detailed to take care of the sick often robbed the hospital of food and supplies.

In late March 1864 Captain Hartmann Heinrich “Henry” Wirz took charge of the prison. The Swiss-born commander, a physician in Louisiana when the war broke out, tried to impose order and security, but his lack of authority over the guards and supply officers limited his effectiveness. He quickly became the primary target of prisoners’ resentment and hostility.

By August the prison population reached its greatest number, with more than 33,000 men incarcerated in the camp. But as Sherman’s troops moved deeper into Georgia, the threat of attacks on Andersonville led to the transfer of most prisoners to other camps, particularly Camp Lawton, near Millen, and Camp Sorghum, in Columbia, South Carolina. By November the prison population was a mere 1,500 men. Transfers back to Andersonville in December brought the number back up to 5,000 prisoners, where it remained until the war’s end five months later.

Prison Security

Andersonville’s garrison consisted of troops from various units over the course of its fourteen months in operation. These included the Fifty-fifth Georgia Infantry, the Twenty-sixth Alabama Infantry, and a battery from Florida. As these troops were called away for combat duty elsewhere, Georgia state reserves and militia from Georgia and Florida replaced them. These grossly outnumbered and poorly armed guards, many of them old men and boys, kept their charges at bay with a “dead line.” A feature of other prisons as well, North and South, this marked strip of ground bordering the stockade walls served as a killing zone for any prisoner who stepped into it. Cannons, guard towers, dog packs, and a second wall also served to foil escapes.

Most of the prisoners who did escape Andersonville fled from work details on duties that took them outside the camp walls. Inmates also attempted to dig at least eighty tunnels, nearly all of which were exposed by informants. Compared with other Confederate prisons, very few of those incarcerated at Andersonville made successful escapes. Those who did escape received help from sympathetic or war-weary white Southerners but found enslaved Blacks to be their greatest allies. Winslow Homer’s famous painting Near Andersonville portrays the irony of the imprisonment of Union soldiers who had come south to free enslaved people.

After the War

On May 7, 1865, just after the war’s end, Captain Wirz and another officer, James W. Duncan, were arrested and tried separately for war crimes by federal military courts in Washington, D.C. Both the defense and the prosecution tried to prove that the defendants were following orders. The prosecutors hoped to prove that Duncan and Wirz were receiving orders from Confederate superiors, including President Jefferson Davis, and the defense attorneys hoped to absolve their clients of responsibility by passing it up the chain of command. After two and a half months, Duncan received a fifteen-year sentence, and Wirz was sentenced to death. Duncan escaped after serving only one year at Fort Pulaski. On November 10, 1865, Wirz was hanged in the courtyard of the Old Capitol prison, just behind the Capitol in Washington.

For decades, historians claimed that Wirz was the only man executed for war crimes committed during the Civil War, and some southerners came to see him as a martyr. The United Daughters of the Confederacy erected a monument to him in the town of Andersonville, and each year on the anniversary of his execution, local residents hold a ceremony paying tribute to him. Wirz was, in fact, one of a few Confederates to be tried and executed for crimes committed during the war. Robert Kennedy, a Confederate officer, was tried and executed by a military tribunal in March 1865 for plotting to blow up New York City landmarks, and Champ Ferguson, a Confederate guerrilla fighter based in Tennessee, was tried and executed in October 1865 for killing Union prisoners of war.

In the decades following the war Andersonville’s notoriety was fueled by memoirs written by former prisoners, many of whom were inspired by public interest in the prison and by efforts to lobby Congress for special veterans’ benefits for POWs. The propagandistic and exaggerated nature of these accounts perpetuated several myths and misconceptions about the prison and its officials. John McElroy’s Andersonville: A Story of Rebel Prisons, published in 1879, provides a good example of the tone and interpretation of narratives written by former prisoners.

Writer MacKinlay Kantor drew on such memoirs for his best-selling novel Andersonville, which won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1956 and was adapted as a television miniseries for Turner Network Television in 1996. Another fictionalized account of the prison’s history is found in Saul Levitt’s 1959 play, The Andersonville Trial, which is based on the Wirz case and serves as a morality tale about criminal acts committed under military orders. The play was adapted for television in 1970.

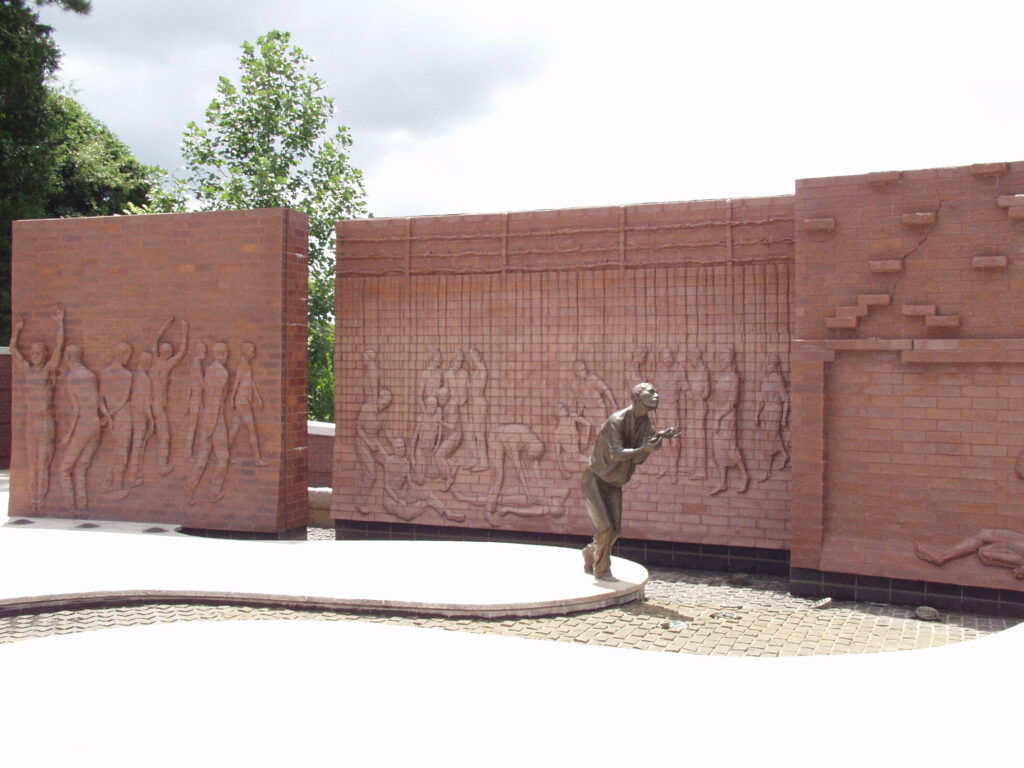

The prison site was preserved as a national cemetery soon after it closed, largely due to efforts by Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross, who worked to have all the graves identified and marked. Andersonville National Historic Site, which lies mostly in Macon County with a small portion in Sumter County, has long been a major tourist attraction. More recently, southerners who felt that Andersonville had unfairly borne the brunt of horror stories of prison treatment campaigned for the creation of a museum at Andersonville to commemorate all American POWs. The National Prisoner of War Museum, which opened in 1998, documents the poor conditions not only at Andersonville but also at Northern camps during the Civil War, as well as those in World War II (1941-45), Korea (1950-53), and Vietnam (1964-73).