Black Georgians resisted enslavement. While the state never experienced a large-scale slave revolt, some Black Georgians actively fought their white enslavers by damaging property, pilfering food, working slowly, running away, plotting attacks, or inflicting small-scale acts of violence.

Eighteenth Century

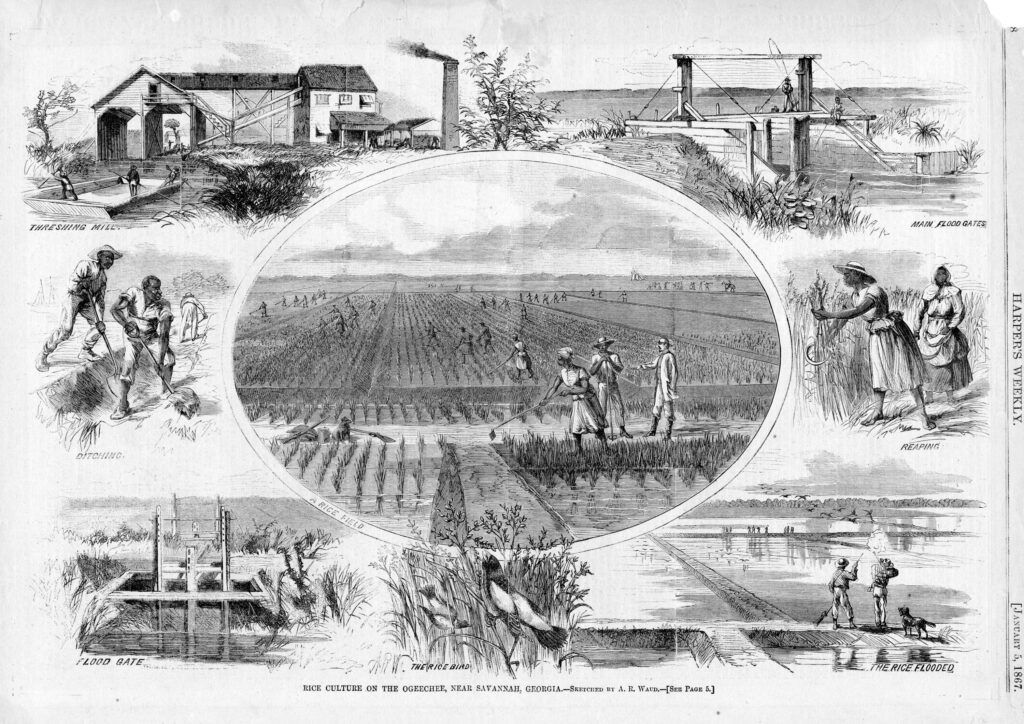

Georgia was the only British colony in North America to initially prohibit slavery. Nevertheless, the population of enslaved Black workers in other colonies gradually but steadily increased. This was particularly the case in neighboring South Carolina, where enslaved workers toiled long hours on plantations producing highly valuable rice and indigo. On September 9, 1739, a group of enslaved workers armed with guns gathered near the Stono River southwest of Charles Town (later, Charleston), South Carolina, with the aim of reaching St. Augustine in Spanish Florida. In response, Georgia General James Oglethorpe called out rangers and issued a proclamation “cautioning all Persons in this Province, to have a watchful Eye upon any Negroes, who might attempt to set a Foot in it.” South Carolina planters and militiamen violently quashed the uprising before it reached Georgia, killing between thirty and fifty Black laborers.

Although the Stono Rebellion—the first and largest slave revolt in North America—fueled fears of future rebellions, demand for enslaved labor only grew. Envious of the immense wealth enjoyed by South Carolina’s planters, Georgia legalized slavery in 1751. The number of enslaved men, women, and children ballooned from around 400 in the early 1750s to more than 16,000 in the 1770s. White Georgians brought enslaved people from neighboring South Carolina and imported thousands of captive Africans into the port of Savannah, which became an important economic center and instrumental node in the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Nevertheless, as slavery became more crucial to Georgia’s economy and the enslaved population continued to grow, fears of Stono still lingered. The colony instituted a formal slave patrol in 1757 to prevent another uprising. Armed white men enforced the racial hierarchy and policed the behavior of enslaved people in towns and the countryside. Authorities imposed laws limiting the ability of Black people to travel, gather, or congregate. A 1770 law, for example, required that every plantation with over twenty-five enslaved people (over the age of 16) retain one white man capable of bearing arms or face a fine.

The Revolutionary War (1775-83) disrupted the lives of both white and Black Georgians. For the enslaved, the war offered the chance of freedom. Whether aiding British or American forces, enslaved people asserted their own right of independence, bargained for their freedom, and otherwise challenged the authority of their enslavers.

In the rural outskirts of Savannah, freedom seeking Blacks self-liberated by forming maroon communities during and immediately after the American Revolution. These communities, comprised of Blacks and indigenous peoples, operated independently in the Lowcountry’s sparsely settled swamps and forests. White authorities felt deeply threatened by the presence of free Blacks in their midst, and militia forces persistently attacked, captured, and tried members of maroon camps. The settlements were never fully uprooted, however, and maroon communities existed in sparsely settled areas of the state until the Civil War (1861-65).

Nineteenth Century

In the face of this repression, Black men and women actively contested their status and condition through “everyday acts of resistance.” Enslaved women working within the white household, for example, burned food, broke china, soiled linens, rent clothing, and pilfered small items. Those working in the fields intentionally broke tools, worked slowly, or stole additional food.

Other acts of resistance affirmed enslaved people’s humanity and autonomy. In Georgia, teaching an enslaved person to read was outlawed in 1770 and in 1829 the law was expanded to include free men and women of color. Within this context, learning to read was a form of everyday resistance.

To protest mistreatment or harsh punishment, enslaved people occasionally resorted to violence. Enslaved workers committed arson, damaged plantation property, or murdered enslavers. Given their ample access to food, enslaved cooks sometimes poisoned food or water with strychnine or arsenic. While enduring a horrific beating on a Meriwether County plantation, Sarah, an enslaved woman, stabbed the overseer and cut his throat. Found guilty of murder, Sarah was hanged on July 9, 1858. She was one of forty-four enslaved women and 352 enslaved men charged with capital crimes in Georgia between 1767 and 1865.

Large-scale slave revolts were exceptionally rare, and none occurred in Georgia. A rebellion on a ship off Georgia’s Sea Islands in 1803 resulted in the deaths of the white crew, but the enslaved inmates chose to drown themselves at a place now known as Ebos Landing rather than submit to slavery. The episode, sometimes called the “Myth of the Flying Africans,” has proved a rich source for the literary imagination, inspiring, among other works, Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon (1977).

The most notable nineteenth-century revolt, Nat Turner’s Rebellion, occurred in Southampton County, Virginia in August 1831. For many whites, this event confirmed their worst fears, and they became extra vigilant against suspected revolts or gatherings among enslaved and free African Americans. In the wake of Turner’s rebellion, Georgia passed insurrection laws to punish anyone that might attempt something similar. These laws survived even the abolition of slavery and were applied a century later against Communist Party organizer and Black activist Angelo Herndon in the 1930s.

Given the depth of slaveholders’ anxiety, even rumored revolts were harshly punished. In 1835 northern lumbermen were suspected of encouraging enslaved people to revolt in Monroe and Jones Counties. Local authorities executed the leader, “whipped [and] branded” his lieutenant, and arrested a “considerable number” of suspected participants. In Augusta, planters uncovered a plot to seize the arsenal, torch the city, and assault local whites. While the legitimacy of this plot is contested, authorities hanged the alleged leader in 1841.

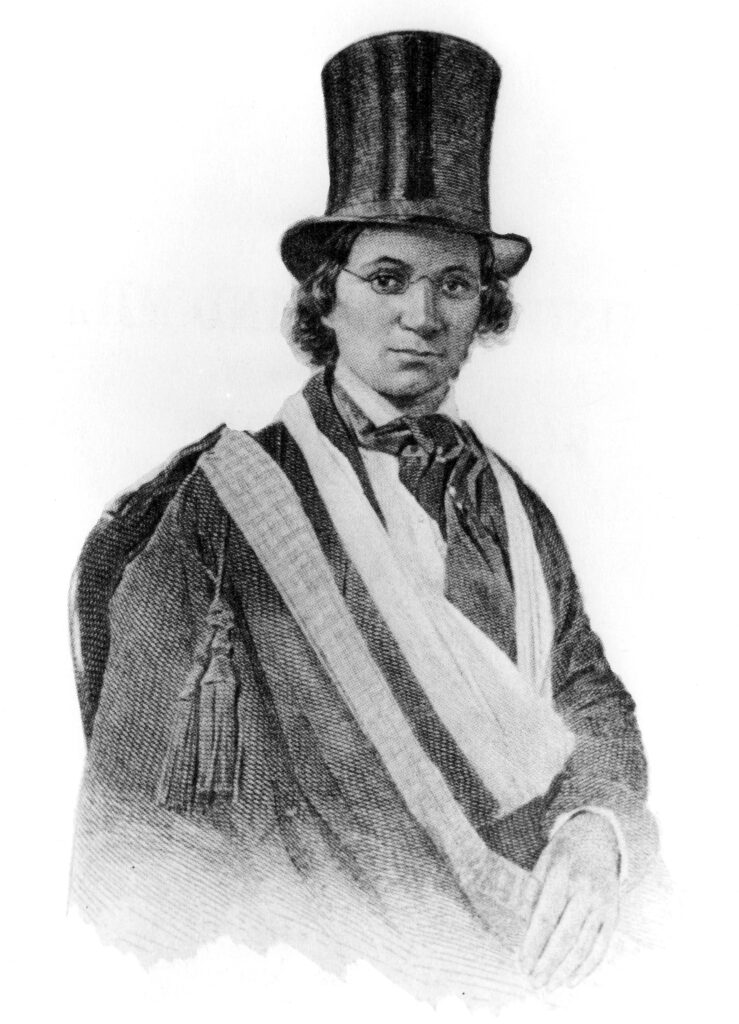

For many enslaved people, self-liberation—or running away—was the ultimate form of resistance. Some departed plantations independently while others absconded with family or friends. William and Ellen Craft, for example, escaped enslavement in Macon as a couple. Ellen, a fair-skinned Black woman, passed as white and William, her husband, posed as her enslaved manservant as they traveled north on trains and a steamship. On December 25, 1848, they arrived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where they later became active abolitionists. Such attempts were extremely risky, as enslavers punished attempted self-liberators with beatings, whippings, brandings, or family separations.

Self-liberation was most successful when aided by whites. Georgia’s enslaved labor force proved a weak link in society that could be exploited in wartime and frequently became a target. In the War of 1812, the British occupied several of Georgia’s Sea Islands and recruited enslaved men to work as scouts and guides, offering to take them and their families to freedom. As many as 2,000 enslaved Georgians were liberated through British action before the war’s end.

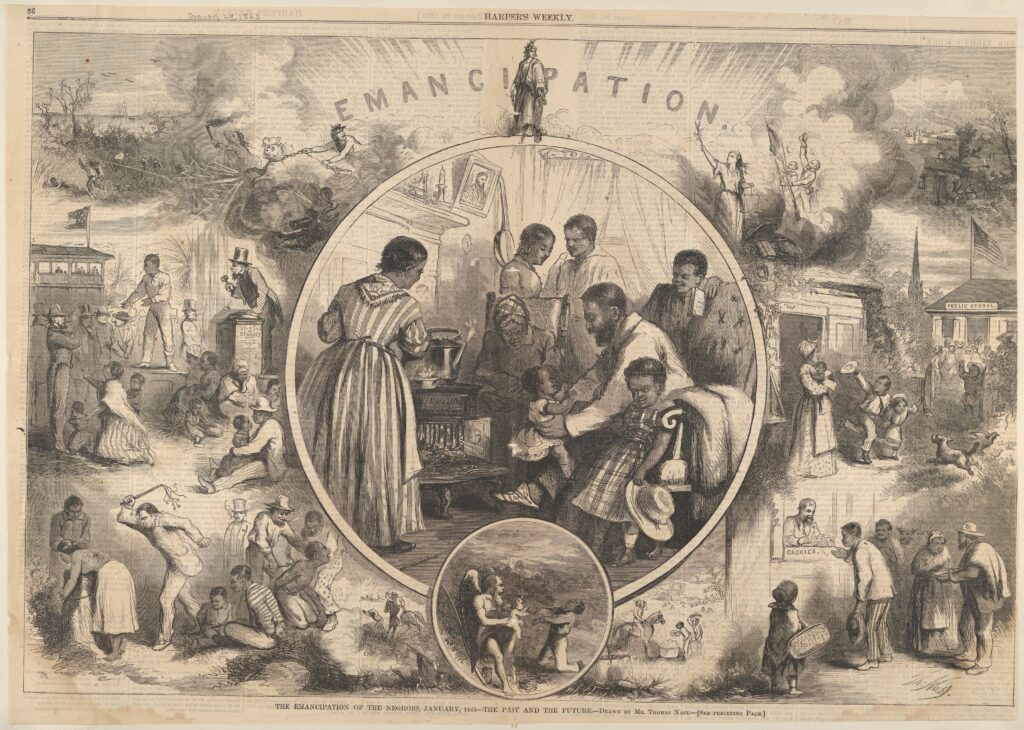

As a conflict over slavery, the Civil War fostered a surge of resistance and rebellion among enslaved people. Holding a deep knowledge of local terrain and on-the-ground conditions, Black men and women shared valuable information and supplies with Union troops. These reports then informed military policy. At the individual level, numerous enslaved people simply stopped working, left plantations, or traveled to Union-held territory. Once free, enslaved men often joined the Union army and fought for Black emancipation.

Yet, even in the midst of war, enslavers attempted to maintain firm control over enslaved workers. On August 22, 1864, four men—John Vickery (a local white man) and Nelson, George, and Sam (enslaved people)—were arrested and executed in Brooks County for conspiring to insurrection. In 2010 the Georgia Historical Society installed a marker in Quitman to commemorate their suppressed revolt.

Fears of racial violence did not end with emancipation. Only months after the end of the Civil War, in December 1865, white southerners feared a Christmas Insurrection. Customarily, enslavers used Christmastime to perform their self-proclaimed “benevolence” by loosening restrictions on large gatherings and distributing gifts to enslaved people. Now, free men and women anticipated this Christmas tradition would continue on a grand scale, a biblical Jubilee involving the redistribution of plantation lands to those who had worked those lands for generations. The promises of such redistribution by US government and army officials only encouraged both the hopeful excitement of freedpeople and the anxious fears of elite white southerners. In Georgia, Union General Rufus Saxton had promised to “aid you in getting 40-acre farms as homes.” As it became increasingly clear that such promises would go unfulfilled, however, white planters worried that armed African Americans would take the land—and possibly their lives too—by force. The 1865 Christmas season came and went without incident, but white southerners remained distrustful of their Black neighbors for decades to come.