In the spring of 1922, Georgia’s “Fiddlin’ John” Carson became one of the first old-time country musicians to broadcast country music over a radio station. A year later, on June 14, 1923, Carson recorded his first phonograph record, which quickly sold out and increased national interest in southern rural music.

The events of John William Carson’s birth remain a matter of some dispute. Some sources indicate that he was born on a Cobb County farm—a telling later affirmed by his younger siblings. Carson himself claimed Fannin County in north Georgia and a third story places him in nearby Gilmer. Dates of birth are likewise unclear, running from 1868 to 1874. But whatever the particulars of his birth, he is known to have moved as a child to Marietta, where his father, James P. Carson, worked on constructing the Western and Atlantic Railroad.

Carson made his living as a farmer, railroad worker, horse jockey, and moonshiner before his talent as a musician was discovered. Between 1913 and 1935 Carson was a major figure at the Georgia Old-Time Fiddlers’ Conventions, held annually in Atlanta. A favorite among contesting fiddlers, he was a colorful character who knew the value of publicity and understood how to cultivate it. He played upon his rural north Georgia origins and regaled audiences with tales about making moonshine, hardscrabble farming, and time spent in jail. He frequently brought his fiddle to the contests in a flour sack. On one occasion he brought along his dog, Old Trail, a hound he had trained to vocalize in accompaniment to its master’s fiddling.

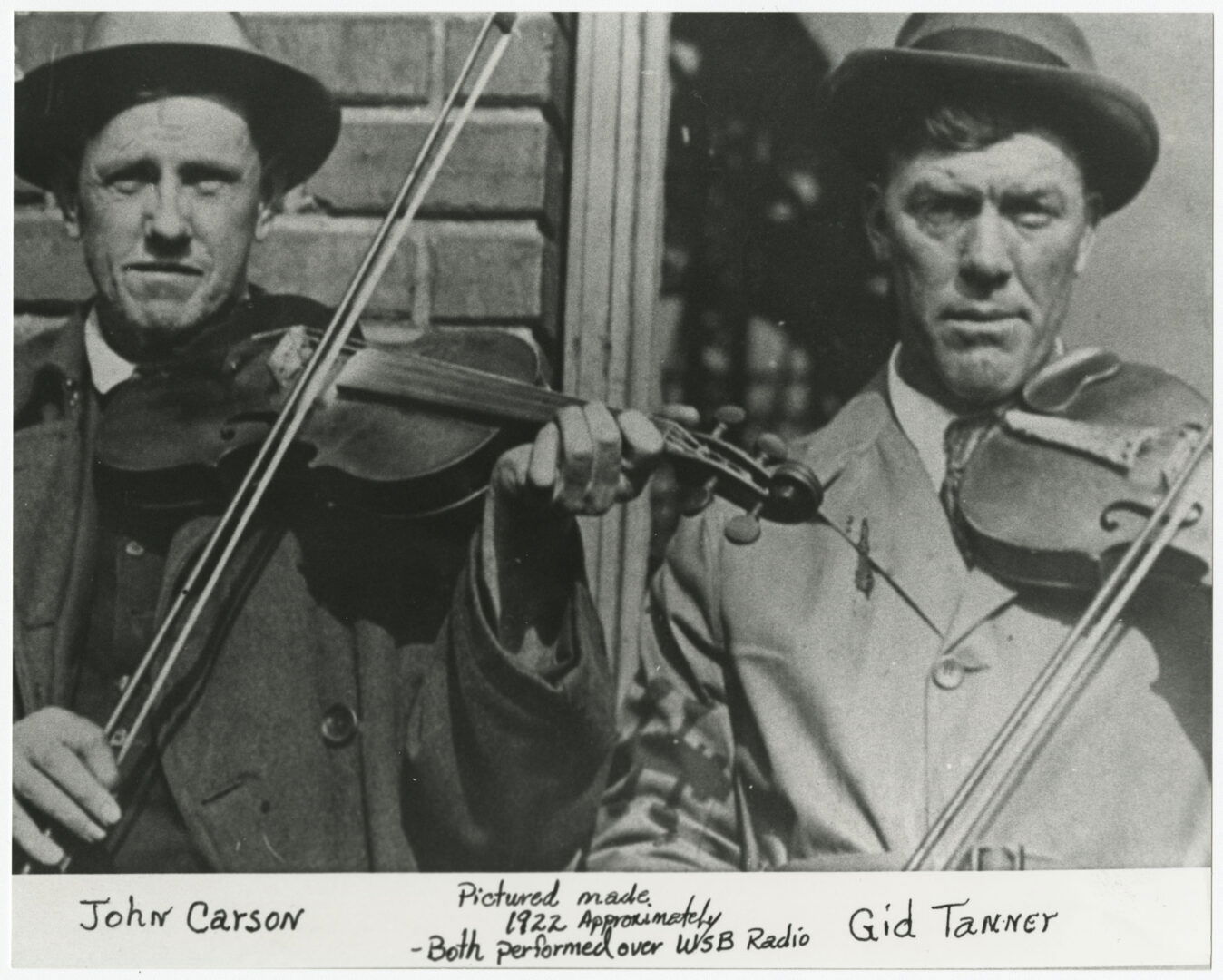

When Atlanta’s WSB, the South’s first radio station, went on the air on March 16, 1922, Fiddlin’ John Carson took notice. A week later, fiddle in hand, he visited the studios to inquire about being allowed to have a try at this latest marvel of entertainment technology. Taking his place before the microphone, Carson launched into an impromptu concert of mountain music that lasted, according to one station official, until “exhaustion set in.” The response from listeners was instantaneous and profuse. Telephone calls, telegrams, and letters poured in for days afterward. Carson was a regular performer on WSB into the early 1930s and thereafter, intermittently, into the 1940s. In those early days of radio, when the air was clear and broadcasting stations were few, WSB’s signal could be picked up as far away as the Rocky Mountains, New York, Cuba, and Canada. Carson, therefore, became a national radio personality.

Carson began making records in 1923, when Ralph Peer, impresario of New York-based OKeh Records, reluctantly allowed him to record two songs, “The Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane” and “The Old Hen Cackled and the Rooster’s Going to Crow,” at an improvised recording studio on Nassau Street in downtown Atlanta. Though Peer had misgivings about the recording—he famously called it “pluperfect awful”—the record-buying public depleted the initial supply of 500 records within days, and company record-pressing facilities were rushed into service to fill back orders. When sales reached half a million, the company greatly altered its assessment of Fiddlin’ John Carson’s abilities. Carson was called to New York to record more of the music from his considerable repertoire of old-time ballads and traditional fiddle tunes. His recording career, which yielded some 165 recorded songs, lasted into the 1930s.

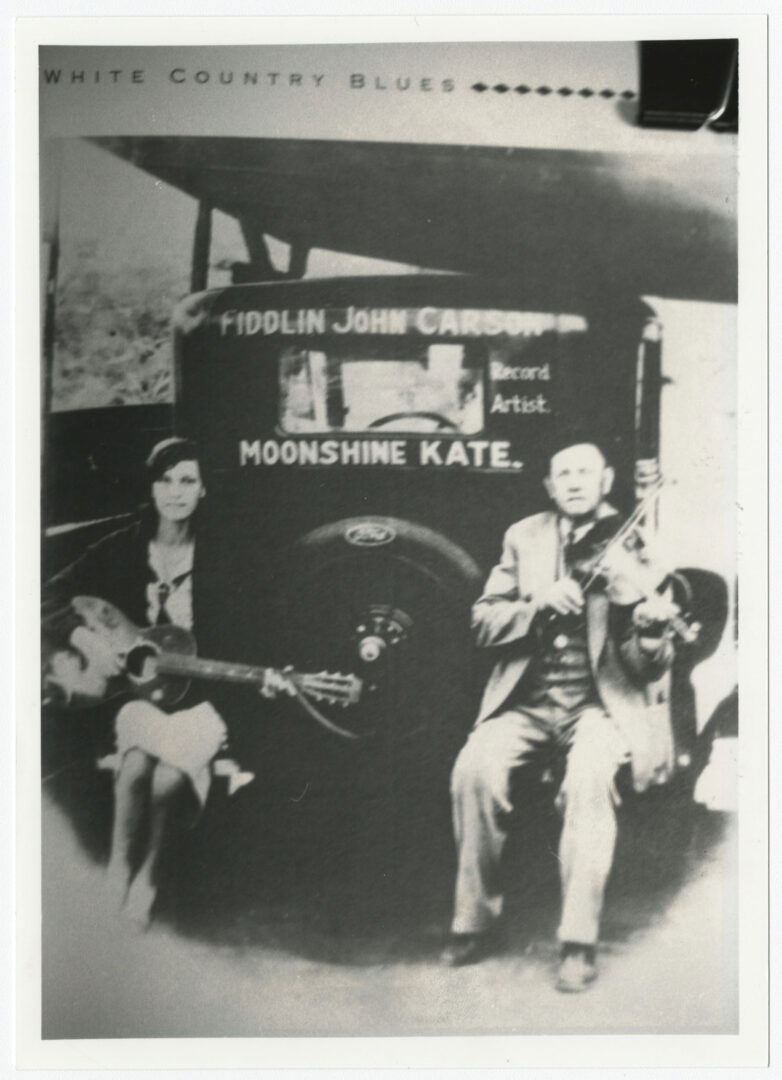

Carson was frequently accompanied on radio, records, and stage by his daughter Rosa Lee (1911-92), a guitarist, singer, and dancer. Under the pseudonym Moonshine Kate, Rosa Lee established herself as an independent performer, thus becoming a pioneer among women country music performers. In 1925 she recorded “Little Mary Phagan,” a ballad composed by her father ten years earlier in response to the Leo Frank case. The song proclaims the guilt of Frank, a Jewish factory manager convicted of killing thirteen-year-old Mary Phagan, one of his employees. Although today Frank is widely considered to be the innocent victim of anti-Semitism, the ballad, which Carson performed in 1915 on the steps of the state capitol, expressed the sentiments of many Georgians at the time. Around 1925 he also recorded another song related to the case, “The Grave of Little Mary Phagan.”

Fiddlin’ John Carson spent the last years of his life as an elevator operator in Georgia’s state capitol, a job earned as a reward for years spent entertaining prospective voters at campaign rallies for Georgia governors Eugene Talmadge and Herman Talmadge.

Despite his contributions to the broader field of country music, Carson remains underappreciated by the Nashville establishment. When asked to account for his omission from the Country Music Hall of Fame, Carson’s daughter, Rosa Lee, indicated it wasn’t so complicated. “Honey, we weren’t country musicians,” she said. “We were hillbillies.”

In 2019 the City of Atlanta issued a demolition permit for the building at 152 Nassau Street, where Carson’s first recordings were made. Despite a great hue and cry from area preservationists, the building was razed to make way for a Margaritaville.