Islam, the world’s second largest religion, has nearly two billion adherents known as Muslims. While proportionally few in Georgia (around eleven to twelve of every thousand residents), Muslims have lived in the state since the colonial era.

Islam is a monotheistic religion that worships the same Abrahamic God reverenced by Judaism and Christianity. Like Judaism, Islam is more concerned with right living (orthopraxy) than right belief (orthodoxy). Although Muslims in Georgia come from diverse backgrounds with varied linguistic and cultural traditions, Islamic beliefs are rooted in the Arabic language. Islam is an Arabic term that roughly translates into English as “submission or commitment to the will of God,” while a Muslim is “one who submits or commits to the will of God.” Muslims address Deity as Allah, Arabic for “God” and the same term used by Arabic-speaking Christians. The scripture for Muslims is the Qur’an, meaning “recitation.”

Early History and Beliefs

Muslims believe this divine recitation was given to God’s Messenger Muhammad (circa 570–632 CE), an Arabian merchant who became a religious figure after the angel Gabriel appeared to him. Muhammad’s teachings clashed with the polytheistic religions that dominated his hometown of Mecca, and he and other Muslims migrated to the city of Medina to escape assassination in 622 CE. This migration, known as the hijra, marks the starting year of the Islamic calendar. Muhammad and other Muslims then faced down military opposition from Mecca and won, capturing the city and destroying its idols. By Muhammad’s death in 632 CE, the major tenets of Islam were in place and the religion dominated the Arabian Peninsula.

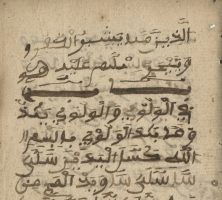

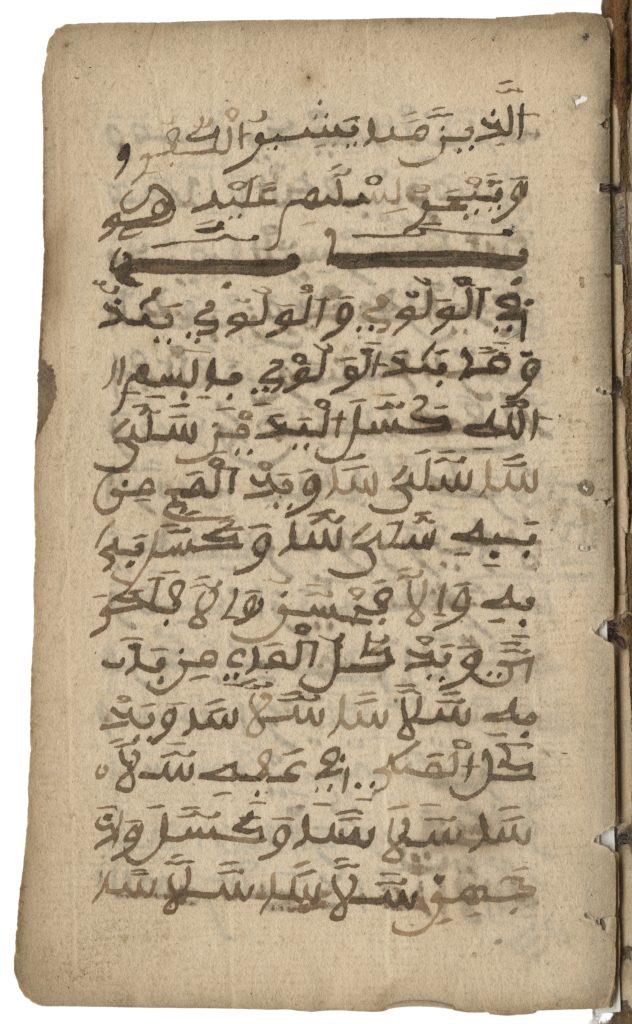

The Islamic declaration of faith, or Shahada, can be translated as, “There is no god but God, and Muhammad is his messenger.” Muslims do not worship Muhammad but honor him like Moses and Jesus and believe he was God’s last messenger to humanity. Muslims believe that the words of previous divine messengers became corrupt and only accept the Qur’an in the original Arabic, believing it to be God’s literal word. They accordingly treat each Qur’an with care and dismiss other language translations as human interpretations.

Since Islam focuses on practice over theology, Muslims also seek inspiration from Muhammad’s Sunnah or Sunna (example), conveyed in the hadith (traditions). Disagreement after Muhammad’s death over which traditions and sayings were accurate and how to interpret them led to Islam’s split into two main factions: Sunni and Shi’i.

These factions disagreed over who should next lead the expanding ummah or umma, meaning community of believers. The majority favored any devout Muslim who followed Muhammad’s Sunnah as caliph, or successor. A fervent minority favored only Ali, Muhammad’s son-in-law, insisting that all future caliphs must descend through Muhammad’s family. This split between Sunni (anyone following Muhammad’s example) and Shi’i (shorthand for a phrase meaning partisans of Ali) continues into the present. While Islam values the commonality of the ummah, the split between Sunni and Shi’i has occasionally flared into violence.

Despite these factions, Muslim armies added much of the Middle East, Central Asia, North Africa, and the Iberian Peninsula to their control. Forced conversions were discouraged by Shari’a, or Islamic law, while Jews and Christians, viewed as “peoples of the book” who had received God’s previous messengers, were largely respected. The unified caliphate eventually fractured, and ever since Muslims have lived in many different political entities.

Islam’s Arrival in Western Africa and Georgia

Muslim traders from North Africa first brought Islam across the Sahara Desert to West Africa in the seventh and eighth centuries, but the religion expanded unevenly in the region. Some West African kings declared the Shahada and became Muslims, but also continued traditional African religious practices.

Warfare among West African kingdoms led to the enslavement and trading of those captured. When Europeans expanded this African slave trade into the Atlantic basin in the sixteenth century, enslaved Muslims were among those taken to the Americas. Few were sent to British North America compared to the sugar islands of the Caribbean and Brazil, but once Georgia’s trustees allowed slavery in the colony after 1750, enslaved African Muslims made their first arrival in the colony.

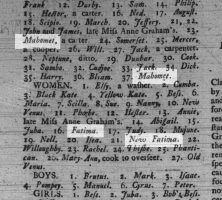

Islam practiced by enslaved Africans took deepest root in coastal Georgia, where Africans frequently outnumbered white enslavers and distinctive African practices (including Islam) survived the longest. Historical records documenting these early Georgia Muslims are few but include uniquely Islamic names among enslaved laborers as well as observations by white residents of notable Islamic customs.

Islamic religious practice is rooted in a set of devotions that are often described as the Five Pillars of Islam. They include the Shahada; salat or daily prayer made in the direction of Mecca; sawm or fasting from sunrise to sunset during the holy month of Ramadan; zakat or the giving of alms to the poor; and the hajj—a pilgrimage made by those who are physically and financially able to the sacred sites in Mecca. Due to the constraints of slavery, few African Muslims in Georgia could pay zakat or make the hajj, but white contemporaries observed enslaved Muslims practicing the remaining three.

Two of Georgia’s best-known early Muslims who practiced these devotions were Salih Bilali of St. Simons Island and Bilali Mohammed of Sapelo Island. White observers noted that Salih Bilali strictly observed the Ramadan fast and declared the Shahada on his deathbed, while Bilali Mohammed, usually known just as Bilali, prayed facing Mecca and kept a small diary of religious meditations in semi-literate Arabic. Since the paper in Bilali’s book was only available in Africa, he may have kept his book secret even while crossing the Atlantic on a slave ship.

The unique devotions of Georgia’s coastal African Muslims were long remembered by their descendants, even though many of the second and third generations gravitated toward Christianity. Interviewers from the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration found many remembrances of Islamic practices among coastal Black residents, which were published in the 1940 book Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies among the Georgia Coastal Negroes. These interviews constitute a rare glimpse into what once was a small community of Muslims in antebellum America.

Twentieth Century Reintroduction and Conflicts

By the end of the nineteenth century, the practice of Islam in Georgia had largely vanished. The emancipated descendants of enslaved African Muslims embraced Christianity, while new Muslims immigrating from foreign countries in that era bypassed opportunity-poor Georgia.

This demographic pattern began to change after World War I (1917-18) when several movements loosely based on Islam and frequently connected with Black nationalism emerged in the northern United States. Energized by the Great Migration of African Americans from the South, these movements proclaimed Islam to be the true religion of the African diaspora. These groups borrowed from Islamic beliefs and practices to bolster Black self-respect and gain independence from white supremacy.

Two early movements in this tradition were the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, which first emerged in India, and the Black nationalist Moorish Science Temple of America founded by Noble Drew Ali. Both groups adapted and altered Islamic doctrines, and both proved attractive to many African Americans tired of legal and cultural racism. While Georgia was peripheral to both movements, some Black Georgians joined the movements after being introduced by northern relatives.

Far more famous and connected to Georgia was a third movement that built on the previous two: the Nation of Islam. A native of Sandersville who grew up in Cordele, Elijah Poole moved north in the Great Migration to escape the depredations of Jim Crow. While in Detroit, he heard a speech by the Nation’s founder, Wallace Fard Muhammad, that proposed Islam as a tool for Black empowerment. Poole soon joined the movement, changed his name to Elijah Muhammad and, upon Fard’s death, assumed leadership of the Nation of Islam. Elijah Muhammad preached Black self-sufficiency and pride, arguing that Blacks were God’s original people while whites sprang from the devil.

One northern convert to the Nation of Islam was Malcolm Little, a reformed convict and the son of a Georgian father from Taylor County. Following a practice encouraged by Elijah Muhammad, Little changed his last name to X. As a spokesman for the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X critiqued the non-violent activism favored by Martin Luther King Jr. and other prominent civil rights leaders. After making the hajj to Mecca and seeing Black Muslims worship in equality with white Muslims, Malcolm X distanced himself from the Nation of Islam before being assassinated in 1965.

The Nation of Islam gained converts in Georgia, and Elijah Muhammad delivered a major speech in Atlanta to possibly more than 3,000 in 1960. During the civil rights movement, Muhammad slowly adopted a less militant posture. Upon his death in 1975, Muhammad was succeeded by his son, Warith Deen Mohammed, who shifted the group toward mainstream Sunni belief and practice. Mohammed also dropped the name the Nation of Islam before a splinter group reclaimed it and restored much of Elijah Muhammad’s original teachings. Many of Georgia’s African American Muslims now follow either more traditional Sunni practice or are associated with the Nation of Islam.

With a major overhaul of immigration laws in 1965, foreign-born Muslims came to the United States in greater numbers. As Georgia became more prosperous in the 1970s, an increasing number of Muslim immigrants settled in the state, especially around Atlanta. These immigrants often retained their cultural and organizational distinctiveness by establishing ethnic-oriented masjids (the proper Arabic term for mosques) to worship apart from previously established masjids dominated by African Americans. For example, the Atlanta Masjid of Al-Islam was previously a temple used by the Nation of Islam but was converted in the 1970s into a Sunni-oriented mosque. Most immigrant Muslims, however, chose to attend Al-Farooq Masjid, first established in 1980, which catered to a largely international congregation. Also arriving in Atlanta were Shi’i Muslims, including the Ismaili sect, which opened their Jamatkhana (congregational place) in 1989.

While many Georgians found Islam curious at the close of the twentieth century, few feared it. Instability and violence in Iran and Arab nations where Islam dominated began to change American perceptions, however.

Twenty-First Century Challenges

Muslim Georgians found themselves blindsided by the September 11 terrorist attacks in 2001. Much as the Ku Klux Klan had appropriated Christian symbols and sayings to pursue violent political objectives, the terrorist organization al-Qaeda appropriated Islamic culture and practices in pursuit of its goals. As was the case nationwide, Georgia’s Muslims suddenly faced intense scrutiny.

Though many non-Muslim Georgians distinguished their Muslim neighbors from terrorists, others were less discerning. In 2003 an arsonist torched an Islamic center in Savannah, and several mosques around the state were vandalized in the years that followed. The city of Lilburn resisted plans to expand a mosque for two years, while a planned cemetery in Covington occasioned extensive protest and a moratorium on constructing religious sites.

Despite challenges from those who believe Islam is an inherently violent and misogynistic religion, Georgia Muslims have sought to correct harmful stereotypes. In addition to operating mosques and schools (including the Madina Institute and the Georgia Islamic Institute), several Muslims have come together to educate the wider public on Islam. The Islamic Speakers Bureau of Atlanta sponsors presentations that address misinformation about Islam, while the Georgia chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations advocates for Muslims’ rights. Other efforts have showcased the diversity of voices among Muslim women in the state. Atlanta resident Saleemah Abdul-Ghafur edited a volume of perspectives by Muslim women, Living Islam Out Loud, while serving as the editor of the women’s magazine Azizah, founded by another Atlanta resident, Tayyibah Taylor.