Leroy Johnson, a prominent attorney, was an advisor to Atlanta’s civil rights movement in the 1960s. In 1962 he won a state senate seat, becoming the first African American to be elected to the Georgia General Assembly since the end of the Reconstruction era.

Early Life

Leroy Reginald Johnson was born on July 28, 1928, in Atlanta to Elizabeth Heard and Leroy Johnson. He graduated from Booker T. Washington High School in 1945 and earned a bachelor’s degree from Morehouse College in 1949 and a master’s degree from Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University) in 1951. He taught social science in the Atlanta school system from 1950 to 1954 before earning a law degree from North Carolina Central University in 1957. (Johnson could not apply to law school at the racially segregated University of Georgia.) He married Cleopatra Whittington in 1948, and they had one son, Michael Vince.

After receiving his law degree, Johnson became the first African American hired by the Fulton County solicitor general’s office (now known as the district attorney’s office) and worked as a criminal investigator there from 1957 to 1962.

In October 1960, in one of Atlanta’s first civil rights demonstrations, Black college students conducted mass sit-ins at Rich’s Department Store lunch counters. Johnson was one of several community leaders, along with Jesse Hill and Whitney Young, advising the student leaders, who included Julian Bond.

Political Career

Georgia’s county unit system of allocating seats in the General Assembly was overturned in a historic “one man, one vote” court decision in 1962. The ruling resulted in the creation of a predominantly Black senate district in Fulton County, and Johnson won the seat in 1962—making him the first African American to serve in the legislature since 1907. He was also the first African American elected to public office in the Southeast that year. During his first session in 1963, Johnson’s senate colleagues included another freshman legislator from Sumter County, Jimmy Carter, and a second-term senator from Towns County named Zell Miller.

Employees in the segregated state cafeteria balked at serving food to Johnson during that first year, but he persevered and became an influential lawmaker, rising to the position of chairman of the powerful Judiciary Committee.

In 1966 Johnson was personally involved in a national controversy involving a newly elected legislator, Julian Bond (who had years earlier participated in the Atlanta sit-ins). Several days before he was to be sworn into office in January 1966, Bond endorsed statements by John Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, denouncing U.S. intervention in the Vietnam War (1964-73) and supporting those who avoided the draft. This stance so enraged the white legislative leadership that they moved to deny Bond his seat in the House of Representatives. During a hearing held by a specially appointed house committee, Johnson was among those who testified on Bond’s behalf. The house subsequently voted not to seat Bond because of the antiwar comments. Later, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a ruling ordering that Bond be allowed to serve in the legislature.

In 1970 Johnson was instrumental in staging a boxing match at the Municipal Auditorium in Atlanta between former heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali and Jerry Quarry. Ali had been stripped of his title because of his opposition to the Vietnam War and had been unable to fight for more than three years. The bout with Quarry attracted national attention and helped pave the way for Ali to eventually reclaim the heavyweight crown.

Johnson was a candidate in the historic 1973 mayoral race that saw the election of Atlanta’s first Black mayor. Although Johnson was well known among voters and had the endorsement of the Atlanta Constitution, he attracted less than 10 percent of the vote and finished out of the runoff between Maynard Jackson and incumbent white mayor Sam Massell. In 1974 Johnson ran for reelection to the state senate but was defeated by Horace Tate.

During the early 1970s, the administration of U.S. president Richard Nixon and the Internal Revenue Service audited the tax returns of more than fifty Black civil rights leaders and politicians. Johnson was subsequently charged with tax evasion but was acquitted in a federal trial in Atlanta.

For several years during the 1980s, Johnson served as executive director of the Atlanta–Fulton County Recreation Authority. He stepped down from that position in January 1987, after an Atlanta Ethics Board investigation into the handling of fairs in the Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium parking lot. The ethics board said that there was no evidence of wrongdoing on Johnson’s part but criticized him for the appearance of impropriety resulting from his son’s management of a fair in 1986.

In his later years, Johnson remained active in the field of real estate law, advising the Development Authority of Fulton County on bond issues.

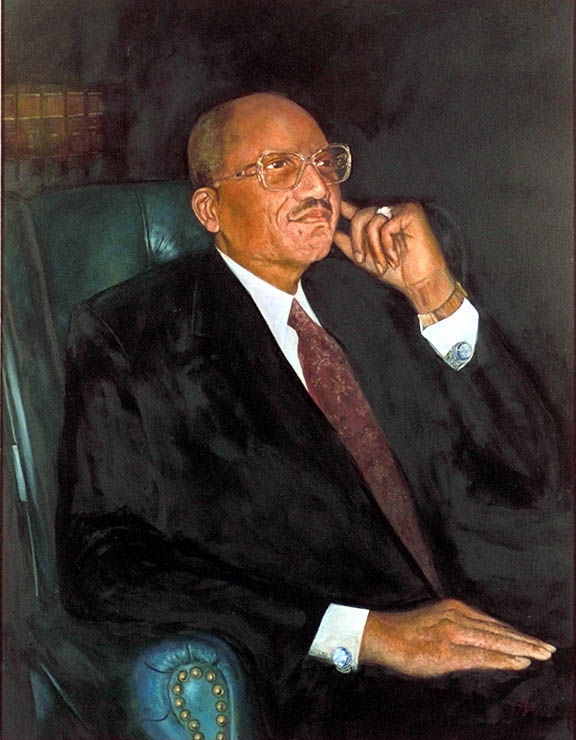

Johnson’s portrait was hung in 1996 on the third floor of the state capitol near the senate chamber, where he served for twelve years. During the 2000 legislative session, the senate unanimously passed a resolution renaming a portion of Fulton Industrial Boulevard as Leroy Johnson–Fulton Industrial Boulevard.

Leroy Johnson died on October 24, 2019.