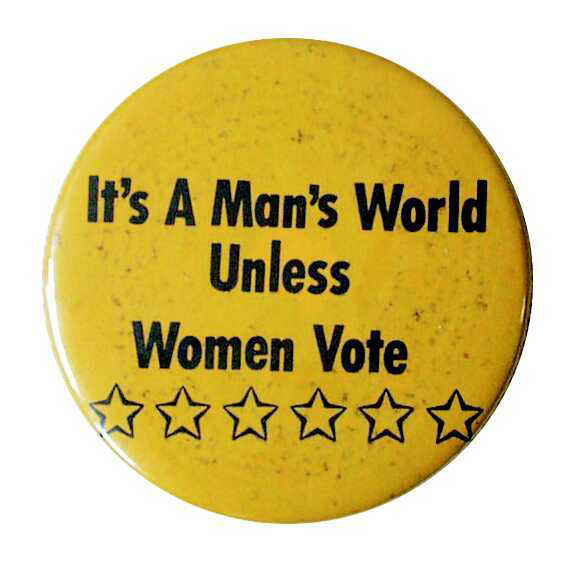

Most southern women did not publicly express a desire for equal rights with men until well after the Civil War (1861-65), and suffrage, or the right to vote, came later to women in Georgia than to women in most other states.

Northern women, inspired by the national reform movements in abolition and temperance, had held the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848, and the first national women’s rights convention in 1850, in Worcester, Massachusetts. In the West, territories such as Wyoming granted suffrage to women long before becoming states. Even though the Nineteenth Amendment, known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, became federal law on August 26, 1920, Georgia women could not vote until 1922. In fact, the amendment was not officially ratified and approved by the state legislature until 1970.

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA), dedicated to human rights, Black suffrage, and woman suffrage, was formed in 1866, the same year Georgia passed legislation giving married women property rights. In 1869, when a woman suffrage amendment was introduced in the U.S. Congress, the AERA split into two factions. The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) was a moderate group led by Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe, and the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was a more radical faction formed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. While the former campaigned to accomplish a state-by-state right to vote, the latter sought a constitutional amendment for the vote and worked for a variety of reforms. The passage in 1870 of the Fifteenth Amendment, stating that citizens could not be denied the vote because of race, color, or former status as a slave, granted Black males the right to vote and to hold office. The belief that women also deserved this right not only increased membership in the pro-suffrage organizations but also led to tension over how best to achieve this in the South.

Organizing for Suffrage

The AWSA and the NWSA reunited in 1890, into a group known as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). In Columbus, Georgia, Helen Augusta Howard formed a branch of the organization she called the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA). In 1892 the NAWSA established the Committee on Southern Work, and by 1893 the Georgia chapter had members in five counties. In 1894 the Equal Suffrage League formed in Atlanta as a chapter of the GWSA. Further impetus for the suffrage movement in Georgia came in 1895, when the NAWSA held their annual meeting in Atlanta, the first held outside of Washington, D.C. The organization’s headquarters was at the Aragon Hotel, and meetings were held at DeGive’s Opera House. Susan B. Anthony and ninety-three delegates from twenty-eight states, together with visitors and reporters, attended.

African American women were excluded from these meetings, but Anthony did speak on the campus of Atlanta University, an all-Black school. In the audience was alumna Adela Hunt Logan, a Georgian who taught at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute. Logan published several suffrage articles and became the NAWSA’s first lifetime member. For African American women, support of NAWSA efforts was seen as a further step toward reenfranchisement for Black men, as well as enfranchisement for themselves. In 1896 several African American women’s organizations formed the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) in Washington, D.C. In the next several years, many members, like Lugenia Burns Hope, wife of John Hope, the first president of Atlanta’s Morehouse College, became suffrage advocates through their work in the NACW.

The GWSA held its first convention in November 1899 in Atlanta. Speakers from Georgia as well as from other southern states attended. Under president Mary Latimer McLendon, the association passed several resolutions, including a statement that Georgia women should not pay taxes if they did not have the vote and a request that the University of Georgia be opened to women. At the November 1901 GWSA convention, Atlantan Katherine Koch was chosen president. In 1902 Atlanta women petitioned to vote in municipal elections but were rejected.

Although no Georgia newspaper ever campaigned aggressively for woman suffrage, the growing activity of the state’s suffrage organizations gained much-needed publicity with the establishment of a woman suffrage department in the Atlanta Constitution in July 1913. Weekly columns appeared in the Atlanta Journal and in theColumbus Ledger, and special editions were published in the Columbus Ledger and in the Atlanta Georgian.

National and State Events

The 1906 Atlanta race massacre further intensified the question of woman suffrage and how to achieve it in the South, where attitudes on gender and race became a defining issue. The year 1908 was a presidential election year, and suffragists asked both parties to include the issue in their platforms, but neither did. The Prohibition Party of Georgia, however, did adopt woman suffrage as part of its platform. The Georgia Federation of Labor had endorsed woman suffrage in 1900. They called for local unions to support it, and events outside the South encouraged them to do so. In 1907 Harriet Blatch, daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, formed the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women to reach out to working-class women. In 1909 the woman suffrage–connected strike of 20,000 women garment workers and a boycott by the wealthy women who purchased clothing was coordinated by the Women’s Trade Union League in New York City. After California gave women the vote in 1911, there were six suffrage states.

In 1913 the Georgia Woman Equal Suffrage League was formed, with many teachers and businesswomen as members. The league’s president was an Atlanta teacher and principal of Ivy Street School, Frances Smith Whiteside, and the sister of U.S. senator Hoke Smith. The Georgia Men’s League for Woman Suffrage, formed by Atlanta attorney Leonard J. Grossman, was a chapter of a national organization. With few members outside Atlanta, its formation was mostly a symbolic one for the movement. The Equal Franchise League of Muscogee County as well as a Macon suffrage association were formed by the end of 1913.

In 1914 women who wanted the GWSA to work more aggressively for suffrage formed the Equal Suffrage Party of Georgia, which by 1915 had member branches in thirteen Georgia counties. In the first five years of the party’s existence its presidents were from Atlanta, Augusta, and Savannah. Several Georgia cities and counties had branches of both suffrage organizations working simultaneously for the same goal but with a different focus.

Anti-suffrage Movement and Pro-suffrage Groups

In the spring of 1914 a Georgia chapter of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, founded in 1895, was formed in Macon. Three months later, it claimed to have 10 state branches and 2,000 members, far more than the pro-suffrage organizations. The leadership included Mildred Lewis Rutherford, head of the Lucy Cobb Institute in Athens and president of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. When the Georgia legislature first conducted hearings on the subject in 1914, sisters Mary Latimer McLendon of Atlanta and Rebecca Latimer Felton of Cartersville, Leonard J. Grossman, James L. Anderson, and Mrs. Elliott Cheatham of Atlanta all addressed the house committee for suffrage. Speaking for the opposition were Rutherford and Dolly Blount Lamar of Macon. The vote was five to two against suffrage, and the resolution did not pass. Hearings were conducted again the following year before committees of the senate and house, and both voted against it.

In March 1914 pro-suffrage women held their first rally in Atlanta, with urban reform leader Jane Addams as speaker. In 1915 a May Day celebration was cause for Atlanta suffragists to gather on the steps of the state capitol. The following November, a significant event in the movement occurred when pro-suffrage groups marched after Atlanta’s Harvest Festival celebration. Patterned after parades held in New York and Washington, D.C., the march included more than 200 students in caps and gowns, marchers wearing “votes for women” sashes and carrying banners, and decorated automobiles, all led by a brass band. Mary McLendon led the vehicles in Eastern Victory, an automobile sold by Anna Howard Shaw to pay “unjust” taxes. A pony cart filled with yellow chrysanthemums carried a large sign reading “Georgia Catching Up.” On horseback, representing the herald leading women “forward into light,” was Eleanore Raoul, organizer of the Fulton and DeKalb Equal Suffrage Party. All of Georgia’s suffrage groups, including the Georgia Young People’s Suffrage Association, were represented. The following year the Atlanta woman suffrage organizations were the first nonlabor group to be included in Atlanta’s Labor Day Parade.

In 1917 Alice Paul formed the National Woman’s Party. Because of the party’s protest of Democratic president Woodrow Wilson’s lack of support for a federal suffrage amendment, their attempts to organize in the South as early as 1915 had failed. In 1917, feeling that the “antis” were gaining too much of the South, the National Woman’s Party increased efforts to recruit in the South, and a Georgia branch was formed. Considered radical by other southern suffrage groups, the National Woman’s Party was a relatively militant organization. Although they did nothing unusual in Georgia, they were the first group ever to picket the White House for a political cause.

Two 1917 events were significant to the suffrage movement: the United States entered World War I (1917-18), and New York women won the right to vote. Although the NAWSA endorsed the war effort, not all suffrage organizations were in agreement. The same year, Georgia suffrage supporters again presented the irresolution to the senate committee. Endorsement was finally achieved by a vote of eight to four in favor, but the senate did not act on that support. Elsewhere in Georgia, the city of Waycross allowed women, many of them property owners, to vote in municipal primary elections. In May 1919, women were allowed to vote in Atlanta municipal primary elections, by a vote of twenty-four to one.

Passage of the Amendment

On June 4, 1919, with the support of only one southern senator, Georgia’s William J. Harris, the U.S. Congress passed the Woman Suffrage Amendment, and it was submitted to the states for ratification. In response, Alabamians formed the Southern Women’s League for the Rejection of the Susan B. Anthony Amendment (Southern Rejection League), and Rutherford became one of its few out-of-state members. On July 24 Georgia became the first state to reject the ratification of the amendment, and both houses adopted resolutions to that effect.

By August 1920 thirty-five states had ratified the Nineteenth Amendment. One more state was needed for full ratification, and the state of Tennessee ratified it on August 18. Although many in Tennessee and the South continued to challenge it, the amendment became effective on August 26. Women finally had won the vote, but Georgia’s women still could not vote in that year’s November elections. Georgia, along with Mississippi, cited a requirement that one must be registered six months before the election in order to vote. Because the legislature refused to pass an “enabling act” to make voting immediately possible, Georgia women did not vote until 1922.

Assured that women had won the vote, the League of Women Voters organized in February 1920 to carry on the work of the NAWSA. In Georgia all branches of the various suffrage societies and leagues merged into the League of Women Voters of Georgia. Through this organization and others, women sought to address the many issues important to them that had been raised, including employment, education, and health care. The Nineteenth Amendment remains a milestone from which women could begin to do this through political means.